Valence Bond Theory

The localized valence bond theory uses a process called hybridization, in which atomic orbitals are combined mathematically to produce sets of equivalent orbitals that are properly oriented to form bonds to create the common electron group arrangements. These new orbital combinations are called hybrid atomic orbitals because they are produced by combining (hybridizing) two or more atomic orbitals from the same atom.

Hybridizing One s Orbital and Three p Orbitals

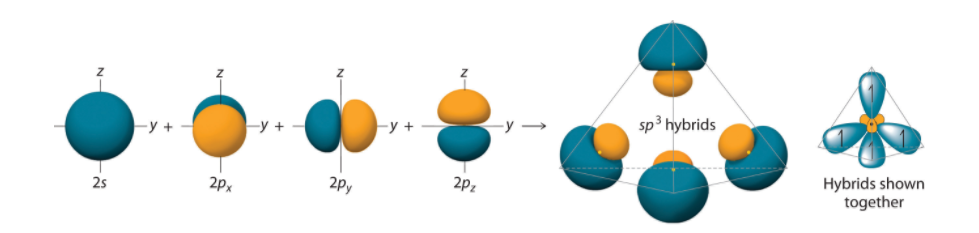

Carbon atoms typically form four covalent bonds, and have electron group arrangement of a tetrahedron because there are four "things attached" to the central C atom. We can explain the tetrahedral shape by proposing that the 2s orbital and the three 2p orbitals on a carbon atom mix together to give a set of four degenerate sp3 (“s-p-three”) hybrid orbitals, each containing a single electron.

The large lobes of the hybridized orbitals are oriented toward the vertices of a tetrahedron, with 109.5° angles between them. Like all the hybridized orbitals discussed earlier, the sp3 hybrid atomic orbitals are predicted to be equal in energy. Thus, methane (CH4) is a tetrahedral molecule with four equivalent C-H bonds.

Figure: Formation of sp3 Hybrid Orbitals. Combining one ns and three np atomic orbitals results in four sp3 hybrid orbitals oriented at 109.5° to one another in a tetrahedral arrangement.

An sp3 hybrid orbital looks a bit like half of a p orbital, and the four sp3 hybrid orbitals arrange themselves in space so that they are as far apart as possible. You can picture the nucleus as being at the centre of a tetrahedron (a triangularly based pyramid) with the orbitals pointing to the corners. For clarity, the nucleus is drawn far larger than it really is.

What happens when the bonds are formed?

Remember that hydrogen's electron is in a 1s orbital - a spherically symmetric region of space surrounding the nucleus where there is some fixed chance (say 95%) of finding the electron. When a covalent bond is formed, the atomic orbitals (the orbitals in the individual atoms) merge to produce a new molecular orbital which contains the electron pair which creates the bond.

Four molecular orbitals are formed, looking rather like the original sp3 hybrids, but with a hydrogen nucleus embedded in each lobe.

Hybrid orbital theory can be applied to molecules of ammonia (NH3) , which has three atoms and one lone pair attached to the central N atom. This means that the N atom is sp3 hybridized. Three sp3 orbitals form bonds with three H atoms, while the fourth orbital accommodates the lone pair of electrons. Similarly, H2O has an sp3 hybridized oxygen atom that uses two sp3 orbitals to bond to two H atoms, and two orbitals to accommodate the two lone pairs predicted by the VSEPR model. Such descriptions explain the approximately tetrahedral distribution of electron pairs on the central atom in NH3 and H2O.