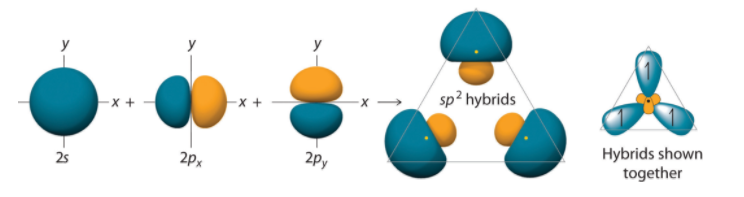

Hybridizing One s Orbital and Two p Orbitals

Ethene, C2H4, is a molecule in which all of the atoms lie in a plane, with 120o bond angles between all of the atoms:

To explain this structure, we can generate three equivalent hybrid orbitals on each C atom by combining the 2s orbital of the carbon and two of the three degenerate 2p orbitals. This mixing results in each C atom possessing a set of three equivalent hybrid orbitals with one electron each. The hybrid orbitals are degenerate and are oriented at 120° angles to each other. Because the hybrid atomic orbitals are formed from one s and two p orbitals, carbon is said to be sp2 hybridized (pronounced “s-p-two” or “s-p-squared”).

Figure: Formation of sp2 Hybrid Orbitals. Combining one ns and two np atomic orbitals gives three equivalent sp2 hybrid orbitals in a trigonal planar arrangement; that is, oriented at 120° to one another.

Two of the sp2 hybrid atomic orbitals on each C atom can can overlap with the s orbitals on two H atoms. The third hybrid orbital on each C atom can overlap to form a sigma bond between the two C atoms. Both C atoms have one 2p orbital that has yet to be used for bonding. When the C atoms form a sigma bond and are pulled close together, a pi bond can also form between the two C atoms because the p-orbitals can overlap above and below the internuclear axis. The result to form a trigonal planar structure.

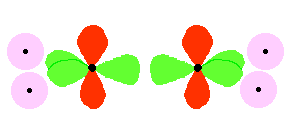

The entire bonding process looks like this (with the sp2 hybrid orbitals in bright green and the unhybridized p orbitals in red):

The two carbon atoms and four hydrogen atoms would look like this before they joined together:

The various atomic orbitals which are pointing towards each other now merge to give molecular orbitals, each containing a bonding pair of electrons. These are sigma bonds - just like those formed by end-to-end overlap of atomic orbitals in, say, ethane.

The p orbitals on each carbon are not pointing towards each other, and so we'll leave those for a moment. In the diagram, the black dots represent the nuclei of the atoms. Notice that the p orbitals are so close that they are overlapping sideways.

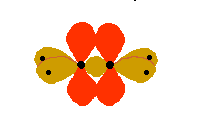

This sideways overlap also creates a bond.

For clarity, the sigma bonds are shown using lines - each line representing one pair of shared electrons. The various sorts of line show the directions the bonds point in. An ordinary line represents a bond in the plane of the screen (or the paper if you've printed it), a broken line is a bond going back away from you, and a wedge shows a bond coming out towards you.

Be clear about what a bond is. It is a region of space in which you can find the two electrons which make up the bond. Those two electrons can live anywhere within that space. It would be quite misleading to think of one living in the top and the other in the bottom.