Hybridizing One s Orbital and One p Orbital

Ethyne, C2H2, is a molecule in which all of the atoms lie in a straight line:

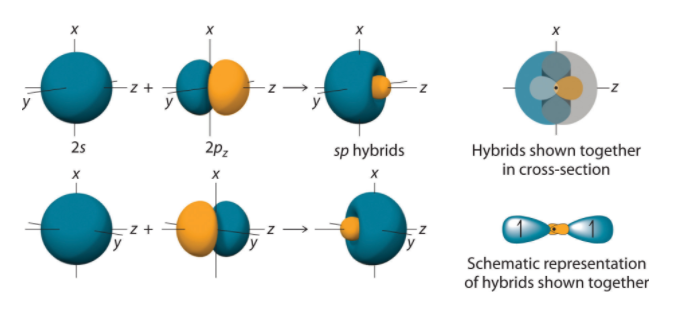

To explain this structure, we can generate two equivalent hybrid orbitals on each C atom by combining the 2s orbital of carbon and any one of the three degenerate 2p orbitals.

By taking the sum and the difference of C 2s and 2pz atomic orbitals, for example, we produce two new orbitals with major and minor lobes oriented along the z-axes.

Figure The Formation of sp Hybrid Orbitals. Taking the sum and difference of an ns and an np atomic orbital where n = 2 gives two equivalent sp hybrid orbitals oriented at 180° to each other.

The nucleus resides just inside the minor lobe of each orbital. In this case, the new orbitals are called sp hybrids because they are formed from one s and one porbital.

One sp hybrid orbital on each C atom can now form a sigma bond with one of the H atoms. The other sp hybrid orbital on each C atom can overlap to form a sigma bond between the two C atoms. Both C atoms have two 2p orbitals that have yet to be used for bonding. These orbitals are perpendicular to each other on each C atom, but when the C atoms form a sigma bond and are pulled close together, two pi bonds can also form between the two C atoms because one set of p-orbitals can overlap above and below the internuclear axis, and the other set of p orbitals can overlap in front of and behind the internuclear axis.

The entire bonding process looks like this (with the sp hybrid orbitals in bright green and the unhybridized p orbitals in red):

Notice that the two green lobes are two different hybrid orbitals - arranged as far apart from each other as possible. Do not confuse them with the shape of a p orbital. The two carbon atoms and two hydrogen atoms would look like this before they joined together:

The various atomic orbitals which are pointing towards each other now merge to give molecular orbitals, each containing a bonding pair of electrons. These are sigma bonds - just like those formed by end-to-end overlap of atomic orbitals in, say, ethane. The sigma bonds are shown as orange in the next diagram. The various p orbitals (now shown in slightly different reds to avoid confusion) are now close enough together that they overlap sideways.

Sideways overlap between the two sets of p orbitals produces two pi bonds - each similar to the pi bond found in, say, ethene. These pi bonds are at 90° to each other - one above and below the molecule, and the other in front of and behind the molecule. Notice the different shades of red for the two different pi bonds.