A reversible reaction can proceed in both the forward and backward directions. Most reactions are theoretically reversible in a closed system, though some can be considered to be irreversible if they heavily favor the formation of reactants or products. The double half-arrow sign we use when writing reversible reaction equations, \leftrightharpoons, is a good visual reminder that these reactions can go either forward to create products, or backward to create reactants. One example of a reversible reaction is the formation of nitrogen dioxide, start text, N, O, end text, start subscript, 2, end subscript, from dinitrogen tetroxide,N2O4

start text, N, end text, start subscript, 2, end subscript, start text, O, end text, start subscript, 4, end subscript, left parenthesis, g, right parenthesis, \leftrightharpoons, 2, start text, N, O, end text, start subscript, 2, end subscript, left parenthesis, g, right parenthesis

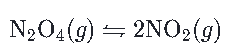

Imagine we added some colorless N2O4start text, N, end text, start subscript, 2, end subscript, start text, O, end text, start subscript, 4, end subscript, left parenthesis, g, right parenthesis to an evacuated glass container at room temperature. If we kept our eye on the vial over time, we would observe the gas in the ampoule changing to a yellowish orange color and gradually getting darker until the color stayed constant. We can graph the concentration of NO2start text, N, O, end text, start subscript, 2, end subscript and N2O4 over time for this process, as you can see in the graph below.

Initially, the vial contains only N2O4start text, N, end text, start subscript, 2, end subscript, start text, O, end text, start subscript, 4, end subscript, and the concentration of NO2start text, N, O, end text, start subscript, 2, end subscript is 0 M. As N2O4 gets converted to NO2start text, N, O, end text, start subscript, 2, end subscript, the concentration of start text, N, O, end text, start subscript, 2, end subscript increases up to a certain point, indicated by a dotted line in the graph to the left, and then stays constant. Similarly, the concentration of N2O4 decreases from the initial concentration until it reaches the equilibrium concentration. When the concentrations of start text, N, O, end text, start subscript, 2, end subscript and N2O4 start text, N, end text, start subscript, 2, end subscript, start text, O, end text, start subscript, 4, end subscript remain constant, the reaction has reached equilibrium.

All reactions tend towards a state of chemical equilibrium, the point at which both the forward process and the reverse process are taking place at the same rate. Since the forward and reverse rates are equal, the concentrations of the reactants and products are constant at equilibrium. It is important to remember that even though the concentrations are constant at equilibrium, the reaction is still happening! That is why this state is also sometimes referred to as dynamic equilibrium.