Equilibrium Constant

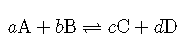

Consider the hypothetical reversible reaction in which reactants and react to form products and . This equilibrium can be shown below, where the lowercase letters represent the coefficients of each substance.

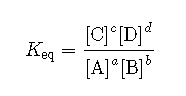

As we have established, the rates of the forward and reverse reactions are the same at equilibrium, and so the concentrations of all of the substances are constant. Since that is the case, it stands to reason that a ratio of the concentration for any given reaction at equilibrium maintains a constant value. The equilibrium constant is the ratio of the mathematical product of the products of a reaction to the mathematical product of the concentrations of the reactants of the reaction. Each concentration is raised to the power of its coefficient in the balanced chemical equation. For the general reaction above, the equilibrium constant expression is written as follows:

The concentrations of each substance, indicated by the square brackets around the formula, are measured in molarity units

.

The value of the equilibrium constant for any reaction is only determined by experiment. As detailed in the above section, the position of equilibrium for a given reaction does not depend on the starting concentrations and so the value of the equilibrium constant is truly constant. It does, however, depend on the temperature of the reaction. This is because equilibrium is defined as a condition resulting from the rates of forward and reverse reactions being equal. If the temperature changes, the corresponding change in those reaction rates will alter the equilibrium constant. For any reaction in which a is given, the temperature should be specified.

When is greater than 1, the numerator is larger than the denominator so the products are favored, meaning the concentration of its products are greater than that of the reactants.

If is less than 1, then the reactants are favored because the denominator (reactants) is larger than the numerator (products).

When is equal to 1, then the concentration of reactants and products are approximately equal.

Reaction Quotient

The reaction quotient, , is used when questioning if we are at equilibrium. The calculation for is exactly the same as for but we can only use when we know we are at equilibrium. Comparing and allows the direction of the reaction to be predicted.

= equilibrium

< reaction proceeds to the right to form more products and decrease amount of reactants so value of will increase

> reaction proceeds to the left to form more reactants and decrease amount of products so value of will decrease