RICE is a simple acronym for the titles of the first column of the table.

R stands for Chemical reaction.

I stands for initial concentration. This row contains the initial concentrations of products and reactants.

C stands for the change in concentration. This is the concentration change required for the reaction to reach equilibrium. It is the difference between the equilibrium and initial rows. The concentrations in this row are, unlike the other rows, expressed with either an appropriate positive (+) or negative (-) sign and a variable; this is because this row represents an increase or decrease (or no change) in concentration.

E is for the concentration when the reaction is at equilibrium. This is the summation of the initial and change rows. Once this row is completed, its contents can be plugged into the equilibrium constant equation to solve for .

The procedure for filling out an RICE table is best illustrated through example.

Checklist for RICE tables

Make sure the reversible equation is balanced at the start of the problem; otherwise, the wrong amounts will be used in the table.

The given data should be in amounts, concentrations, partial pressures, or somehow able to be converted to such. If it is not, then an RICE table will not help solve the problem.

If the RICE table has the equilibrium in amounts, make sure to convert equilibrium values to concentrations before plugging in to solve for .

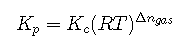

If the given data is in amounts or concentrations, use the RICE table to find . If the given data is in partial pressures, use the ICE table to find . If you desire to convert from one to the other, remember that

It is simpler to use the RICE table with the appropriate givens and convert at the end of the problem.

Enter in known data first, and then calculate the unknown data.

If there is a negative value in the "initial" or "equilibrium" rows, reexamine the calculation. A negative concentration, amount, or partial pressure is physically impossible. Obviously, the "change" row can contain a negative value.

Pay attention to the state of each reactant and product. If a compound is a solid or a liquid, its concentrations are not relevant to the calculations. Only concentrations of gaseous and aqueous compounds are used.

In the "change" row the values will usually be a variable, denoted by x. It must first be understood which direction the equation is going to reach equilibrium (from left to right or from right to left). The value for "change" in the "from" direction of the reaction will be the opposite of x and the "to" direction will be the positive of x (adding concentration to one side and take away an equal amount from the other side).

Know the direction of the reaction. This knowledge will affect the "change" row of the ICE table (for our example, we knew the reaction would proceed forward, as there was no initial products). Direction of reaction can be calculated using Q, the reaction quotient, which is then compared to a known K value.

It is easiest to use the same units every time a RICE table is used (molarity is usually preferred). This will minimize confusion when calculating the equilibrium constants. RICE tables are usually used for weak acid or weak base reactions because all of the nature of these solutions. The amount of acid or base that will dissociate is unknown (for strong acids and strong bases it can be assumed that all of the acid or base will dissociate, meaning that the concentration of the strong acid or base is the same as its dissociated particles).