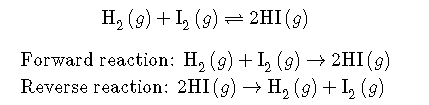

Hydrogen and iodine gases react to form hydrogen iodide according to the following reaction:

Initially, only the forward reaction occurs because no is present. As soon as some has formed, it begins to decompose back into and . Gradually, the rate of the forward reaction decreases while the rate of the reverse reaction increases. Eventually the rate of combination of and to produce becomes equal to the rate of decomposition of into and . When the rates of the forward and reverse reactions have become equal to one another, the reaction has achieved a state of balance. Chemical equilibrium is the state of a system in which the rate of the forward reaction is equal to the rate of the reverse reaction.

Chemical equilibrium can be attained whether the reaction begins with all reactants and no products, all products and no reactants, or some of both. The figure below shows changes in concentration of , , and and present. There is no initially. As the reaction proceeds towards equilibrium, the concentrations of the and gradually decrease, while the concentration of the gradually increases. When the curve levels out and the concentrations all become constant, equilibrium has been reached. At equilibrium, concentrations of all substances are constant.

In reaction B, the process begins with only and no or . In this case, the concentration of gradually decreases while the concentrations of and gradually increase until equilibrium is again reached. Notice that in both cases, the relative position of equilibrium is the same, as shown by the relative concentrations of reactants and products. The concentration of at equilibrium is significantly higher than the concentrations of and . This is true whether the reaction began with all reactants or all products. The position of equilibrium is a property of the particular reversible reaction and does not depend upon how equilibrium was achieved.

Conditions for Equilibrium and Types of Equilibrium

It may be tempting to think that once equilibrium has been reached, the reaction stops. Chemical equilibrium is a dynamic process. The forward and reverse reactions continue to occur even after equilibrium has been reached. However, because the rates of the reactions are the same, there is no change in the relative concentrations of reactants and products for a reaction that is at equilibrium. The conditions and properties of a system at equilibrium are summarized below.

The system must be closed, meaning no substances can enter or leave the system.

Equilibrium is a dynamic process. Even though we don't necessarily see the reactions, both forward and reverse are taking place.

The rates of the forward and reverse reactions must be equal.

The amount of reactants and products do not have to be equal. However, after equilibrium is attained, the amounts of reactants and products will be constant.

The description of equilibrium in this concept refers primarily to equilibrium between reactants and products in a chemical reaction. Other types of equilibrium include phase equilibrium and solution equilibrium. A phase equilibrium occurs when a substance is in equilibrium between two states. For example, a stoppered flask of water attains equilibrium when the rate of evaporation is equal to the rate of condensation. A solution equilibrium occurs when a solid substance is in a saturated solution. At this point, the rate of dissolution is equal to the rate of recrystallization. Although these are all different types of transformations, most of the rules regarding equilibrium apply to any situation in which a process occurs reversibly.

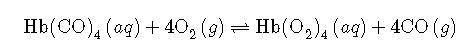

Red blood cells transport oxygen to the tissues so they can function. In the absence of oxygen, cells cannot carry out their biochemical responsibilities. Oxygen moves to the cells attached to hemoglobin, a protein found in the red cells. In cases of carbon monoxide poisoning, binds much more strongly to the hemoglobin, blockin oxygen attachment and lowering the amount of oxygen reaching the cells. Treatment involves the patient breathing pure oxygen to displace the carbon monoxide. The equilibrium reaction shown below illustrates the shift toward the right when excess oxygen is added to the system: