Reversible and irreversible reactions are prevalent in nature and are responsible for reactions such as the breakdown of ammonia. It was believed that all chemical reactions were irreversible until 1803, when French chemist Claude Louis Berthollet introduced the concept of reversible reactions. Initially he observed that sodium carbonate and calcium chloride react to yield calcium carbonate and sodium chloride; however, after observing sodium carbonate formation around the edges of salt lakes, he realized that large amount of salts in the evaporating water reacted with calcium carbonate to form sodium carbonate, indicating that the reverse reaction was occurring.

Chemical reactions are represented by chemical equations. These equations typically have a unidirectional arrow () to represent irreversible reactions. Other chemical equations may have a bidirectional harpoons () that represent reversible reactions (not to be confused with the double arrows ).

Irreversible Reactions

A fundamental concept of chemistry is that chemical reactions occurred when reactants reacted with each other to form products. These unidirectional reactions are known as irreversible reactions, reactions in which the reactants convert to products and where the products cannot convert back to the reactants. These reactions are essentially like baking. The ingredients, acting as the reactants, are mixed and baked together to form a cake, which acts as the product. This cake cannot be converted back to the reactants (the eggs, flour, etc.), just as the products in an irreversible reaction cannot convert back into the reactants.

An example of an irreversible reaction is combustion. Combustion involves burning an organic compound—such as a hydrocarbon—and oxygen to produce carbon dioxide and water. Because water and carbon dioxide are stable, they do not react with each other to form the reactants. Combustion reactions take the following form:

Reversible Reactions

In reversible reactions, the reactants and products are never fully consumed; they are each constantly reacting and being produced. A reversible reaction can take the following summarized form:

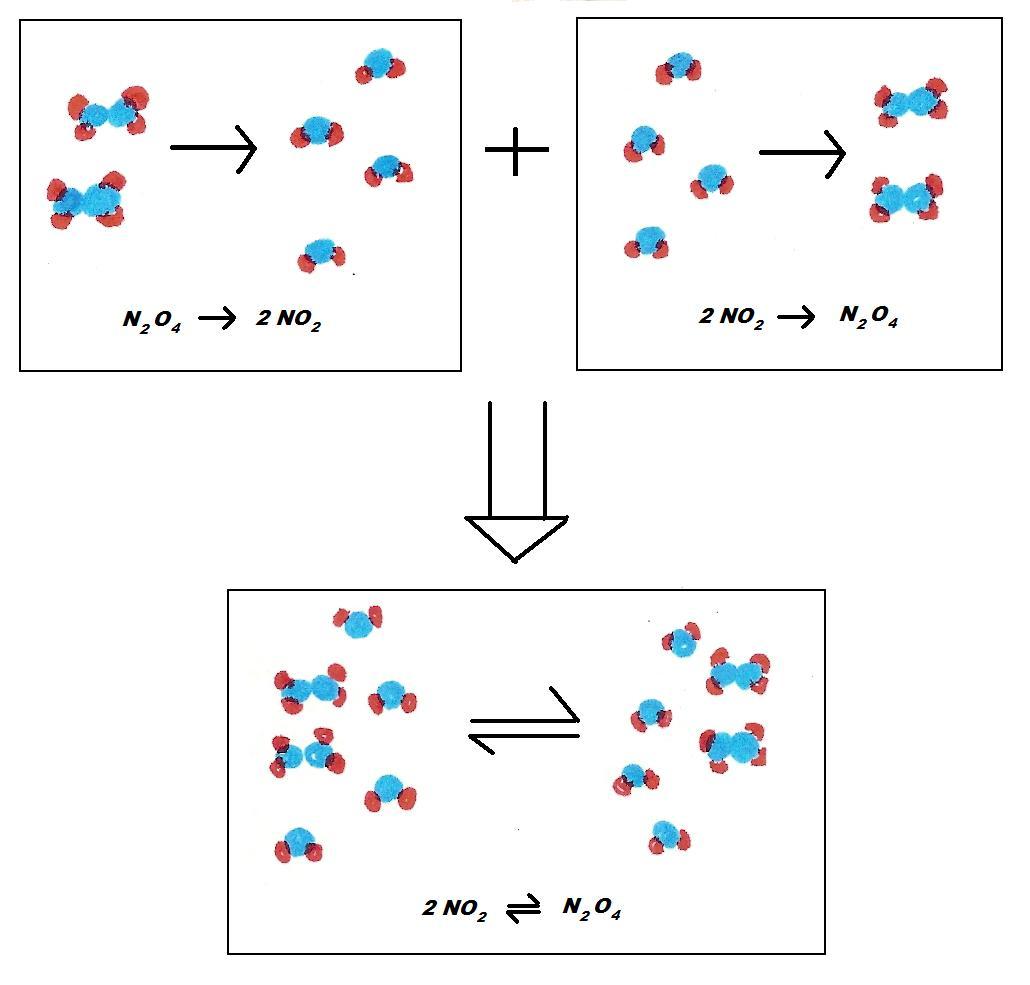

This reversible reaction can be broken into two reactions.

Reaction 1:

Reaction 2:

Below is an example of the summarized form of a reversible reaction and a breakdown of the reversible reaction N2O4 ⇌ 2NO2

Reaction 1 and Reaction 2 happen at the same time because they are in a closed system.

Blue: Nitrogen Red: Oxygen

Reaction 1 Reaction 2

Imagine a ballroom. Let reactant A be 10 girls and reactant B be 10 boys. As each girl and boy goes to the dance floor, they pair up to become a product. Once five girls and five boys are on the dance floor, one of the five pairs breaks up and moves to the sidelines, becoming reactants again. As this pair leaves the dance floor, another boy and girl on the sidelines pair up to form a product once more. This process continues over and over again, representing a reversible reaction.

Unlike irreversible reactions, reversible reactions lead to equilibrium: in reversible reactions, the reaction proceeds in both directions whereas in irreversible reactions the reaction proceeds in only one direction.

If the reactants are formed at the same rate as the products, a dynamic equilibrium exists. For example, if a water tank is being filled with water at the same rate as water is leaving the tank (through a hypothetical hole), the amount of water remaining in the tank remains consistent.