sp3d and sp3d2 Hybridization

To describe the five bonding orbitals in a trigonal bipyramidal arrangement, we must use five of the valence shell atomic orbitals (the s orbital, the three porbitals, and one of the d orbitals), which gives five sp3d hybrid orbitals. With an octahedral arrangement of six hybrid orbitals, we must use six valence shell atomic orbitals (the s orbital, the three p orbitals, and two of the d orbitals in its valence shell), which gives six sp3d2 hybrid orbitals. These hybridizations are only possible for atoms that have d orbitals in their valence subshells (that is, not those in the first or second period).

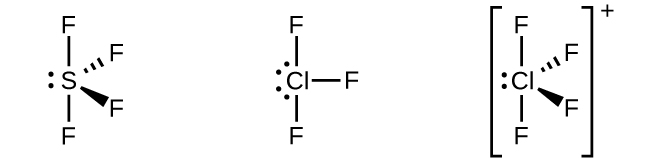

Figure 1 The three compounds pictured exhibit sp3d hybridization in the central atom and a trigonal bipyramid form. SF4 and

have one lone pair of electrons on the central atom, and ClF3 has two lone pairs giving it the T-shape shown.In a molecule of phosphorus pentachloride, PCl5, there are five P–Cl bonds (thus five pairs of valence electrons around the phosphorus atom) directed toward the corners of a trigonal bipyramid. We use the 3s orbital, the three 3p orbitals, and one of the 3d orbitals to form the set of five sp3d hybrid orbitals (Figure 1) that are involved in the P–Cl bonds. Other atoms that exhibit sp3d hybridization include the sulfur atom in SF4 and the chlorine atoms in ClF3 and in . (The electrons on fluorine atoms are omitted for clarity.)

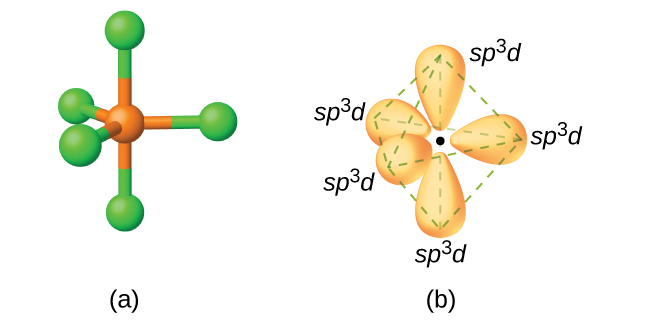

Figure 2(a) The five regions of electron density around phosphorus in PCl5 require five hybrid sp3d orbitals. (b) These orbitals combine to form a trigonal bipyramidal structure with each large lobe of the hybrid orbital pointing at a vertex. As before, there are also small lobes pointing in the opposite direction for each orbital (not shown for clarity).

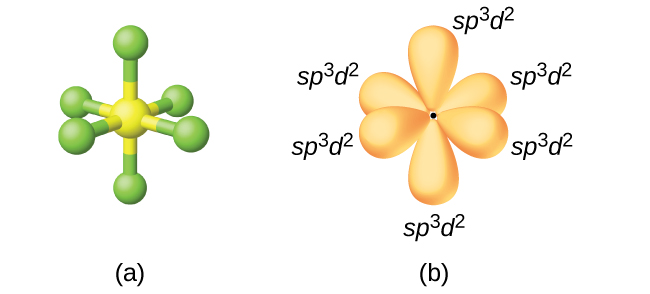

The sulfur atom in sulfur hexafluoride, SF6, exhibits sp3d2 hybridization. A molecule of sulfur hexafluoride has six bonding pairs of electrons connecting six fluorine atoms to a single sulfur atom. There are no lone pairs of electrons on the central atom. To bond six fluorine atoms, the 3s orbital, the three 3p orbitals, and two of the 3d orbitals form six equivalent sp3d2 hybrid orbitals, each directed toward a different corner of an octahedron. Other atoms that exhibit sp3d2hybridization include the phosphorus atom in , the iodine atom in the interhalogens , IF5, , and the xenon atom in XeF4.

Figure 3(a) Sulfur hexafluoride, SF6, has an octahedral structure that requires sp3d2 hybridization. (b) The six sp3d2 orbitals form an octahedral structure around sulfur. Again, the minor lobe of each orbital is not shown for clarity.

Summary of Hybrid Orbitals to Central Atoms

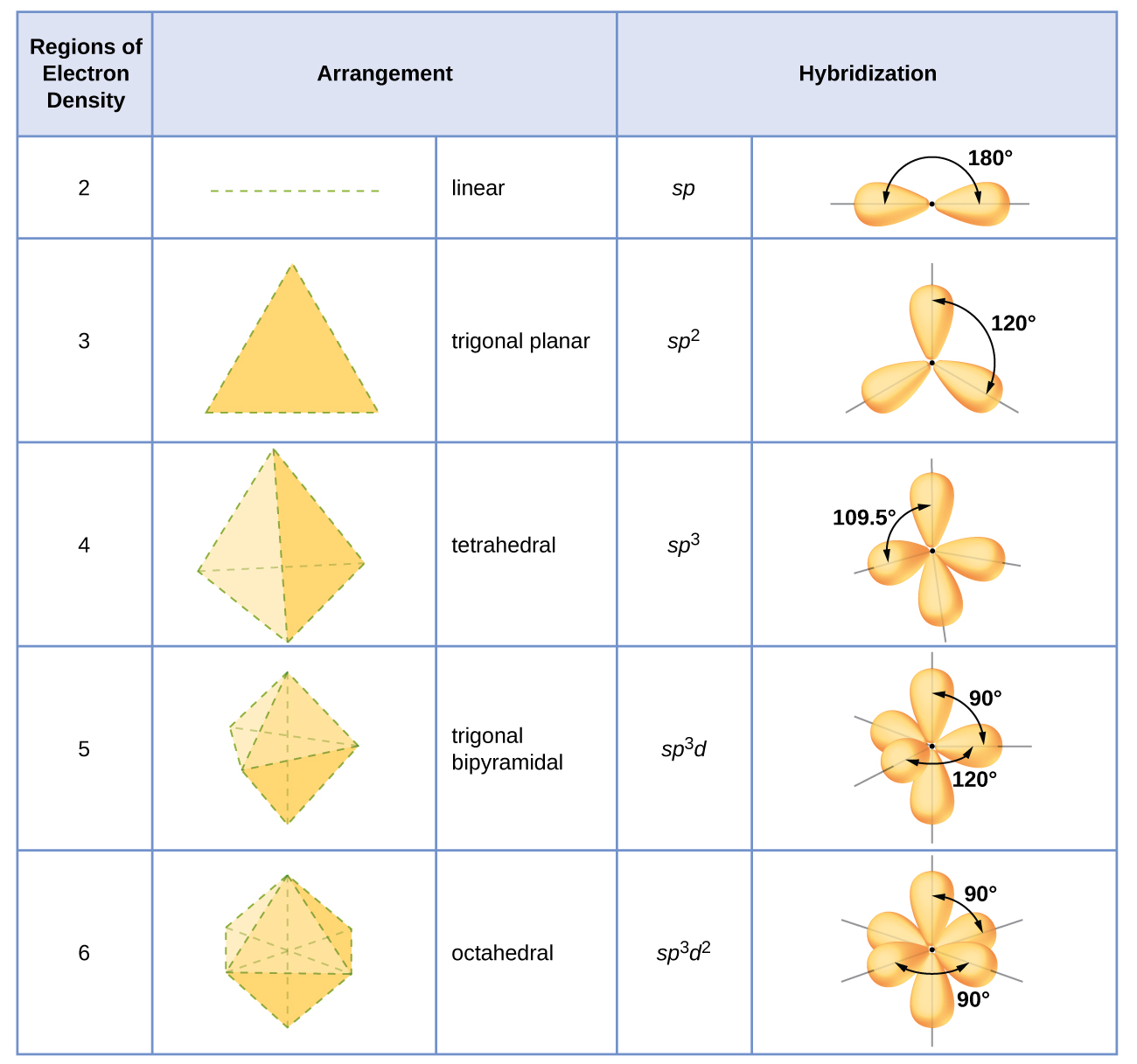

The hybridization of an atom is determined based on the number of regions of electron density that surround it. The geometrical arrangements characteristic of the various sets of hybrid orbitals are shown in the belowing Figure. These arrangements are identical to those of the electron-pair geometries predicted by VSEPR theory. VSEPR theory predicts the shapes of molecules, and hybrid orbital theory provides an explanation for how those shapes are formed. To find the hybridization of a central atom, we can use the following guidelines:

Determine the Lewis structure of the molecule.

Determine the number of regions of electron density around an atom using VSEPR theory, in which single bonds, multiple bonds, radicals, and lone pairs each count as one region.

Assign the set of hybridized orbitals from the belowing Figure.

It is important to remember that hybridization was devised to rationalize experimentally observed molecular geometries, not the other way around.

The model works well for molecules containing small central atoms, in which the valence electron pairs are close together in space. However, for larger central atoms, the valence-shell electron pairs are farther from the nucleus, and there are fewer repulsions. Their compounds exhibit structures that are often not consistent with VSEPR theory, and hybridized orbitals are not necessary to explain the observed data.

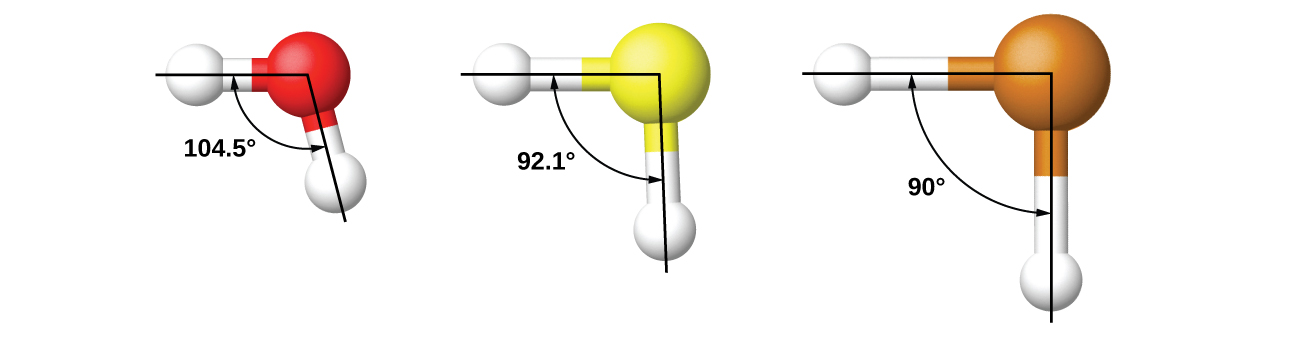

For example, we have discussed the H–O–H bond angle in H2O, 104.5°, which is more consistent with sp3 hybrid orbitals (109.5°) on the central atom than with 2p orbitals (90°). Sulfur is in the same group as oxygen, and H2S has a similar Lewis structure. However, it has a much smaller bond angle (92.1°), which indicates much less hybridization on sulfur than oxygen. Continuing down the group, tellurium is even larger than sulfur, and for H2Te, the observed bond angle (90°) is consistent with overlap of the 5p orbitals, without invoking hybridization. We invoke hybridization where it is necessary to explain the observed structures.