The electron configuration of an element is the arrangement of its electrons in its atomic orbitals. By knowing the electron configuration of an element, we can predict and explain a great deal of its chemistry.

The Aufbau Principle

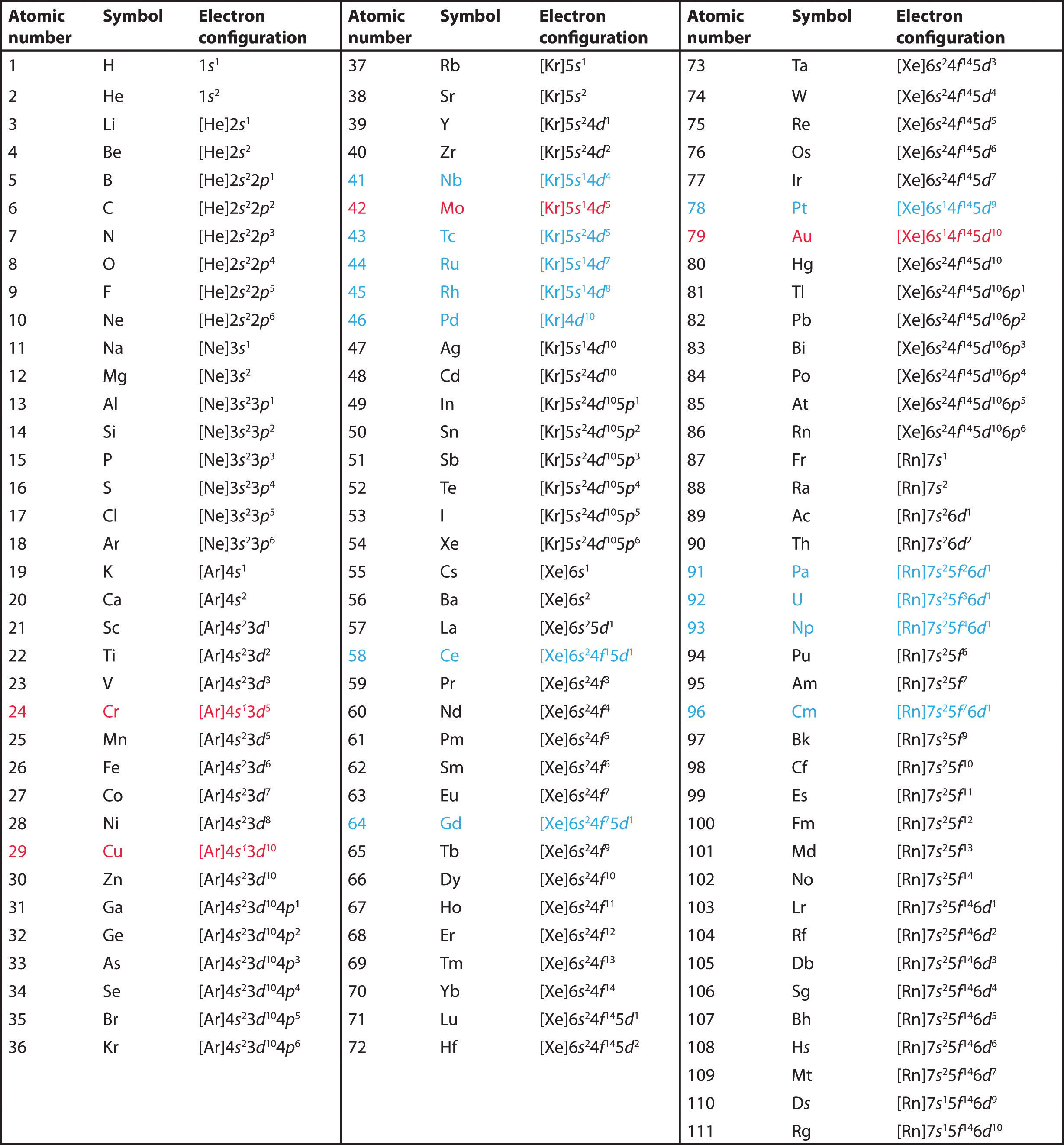

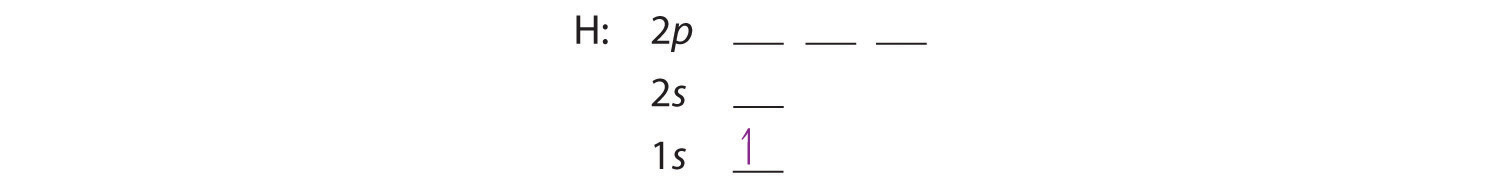

We construct the periodic table by following the aufbau principle (from German, meaning “building up”). First we determine the number of electrons in the atom; then we add electrons one at a time to the lowest-energy orbital available without violating the Pauli principle. We use the orbital energy diagram of Figure 1, recognizing that each orbital can hold two electrons, one with spin up ↑, corresponding to ms = +½, which is arbitrarily written first, and one with spin down ↓, corresponding to ms = −½. A filled orbital is indicated by ↑↓, in which the electron spins are said to be paired. Here is a schematic orbital diagram for a hydrogen atom in its ground state:

From the orbital diagram, we can write the electron configuration in an abbreviated form in which the occupied orbitals are identified by their principal quantum number n and their value of l (s, p, d, or f), with the number of electrons in the subshell indicated by a superscript. For hydrogen, therefore, the single electron is placed in the 1s orbital, which is the orbital lowest in energy (Figure 1), and the electron configuration is written as 1s1 and read as “one-s-one.”

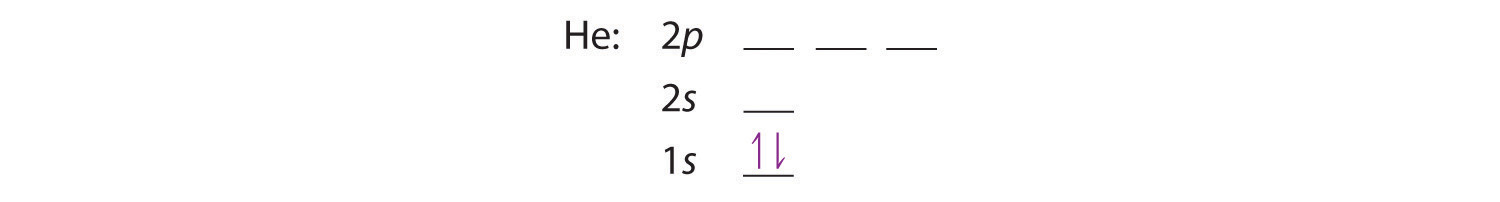

A neutral helium atom, with an atomic number of 2 (Z = 2), has two electrons. We place one electron in the orbital that is lowest in energy, the 1s orbital. From the Pauli exclusion principle, we know that an orbital can contain two electrons with opposite spin, so we place the second electron in the same orbital as the first but pointing down, so that the electrons are paired. The orbital diagram for the helium atom is therefore

written as 1s2, where the superscript 2 implies the pairing of spins. Otherwise, our configuration would violate the Pauli principle.

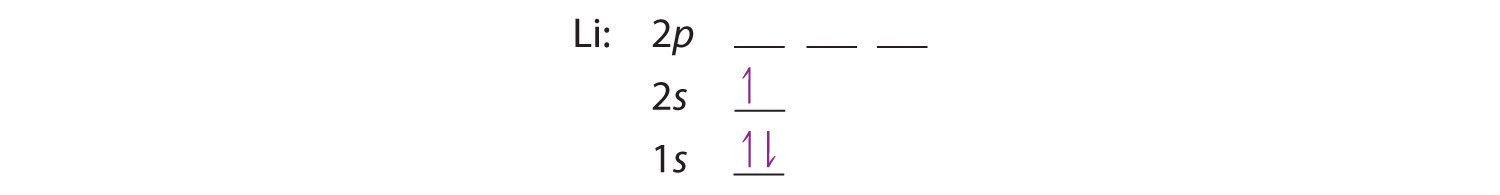

The next element is lithium, with Z = 3 and three electrons in the neutral atom. We know that the 1s orbital can hold two of the electrons with their spins paired; the third electron must enter a higher energy orbital. Figure 6.29 tells us that the next lowest energy orbital is 2s, so the orbital diagram for lithium is

This electron configuration is written as 1s22s1.

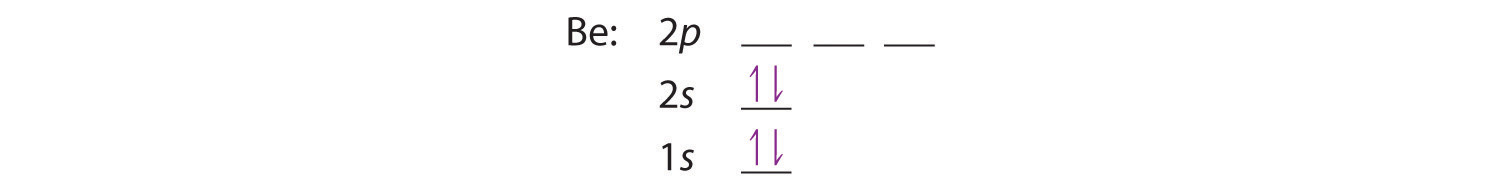

The next element is beryllium, with Z = 4 and four electrons. We fill both the 1s and 2s orbitals to achieve a 1s22s2 electron configuration:

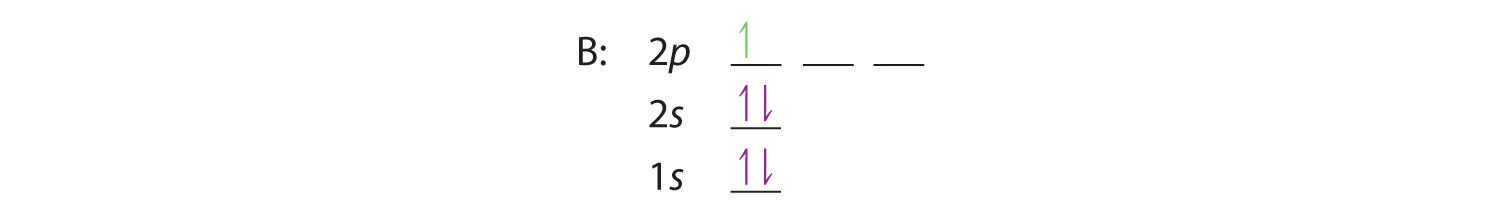

When we reach boron, with Z = 5 and five electrons, we must place the fifth electron in one of the 2p orbitals. Because all three 2p orbitals are degenerate, it doesn’t matter which one we select. The electron configuration of boron is 1s22s22p1:

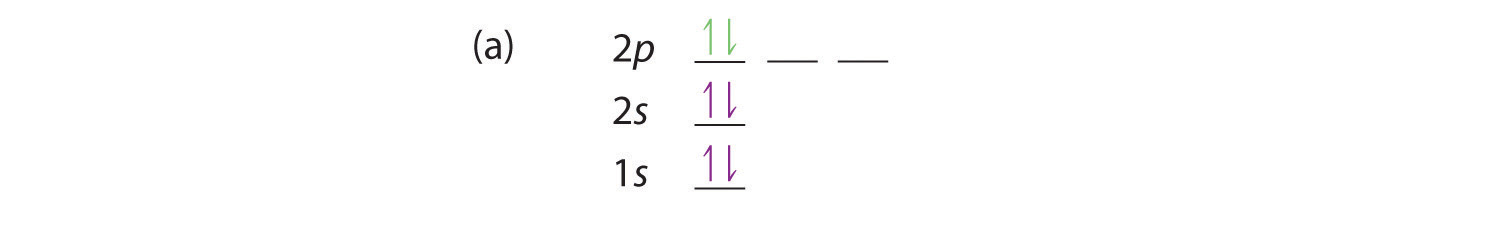

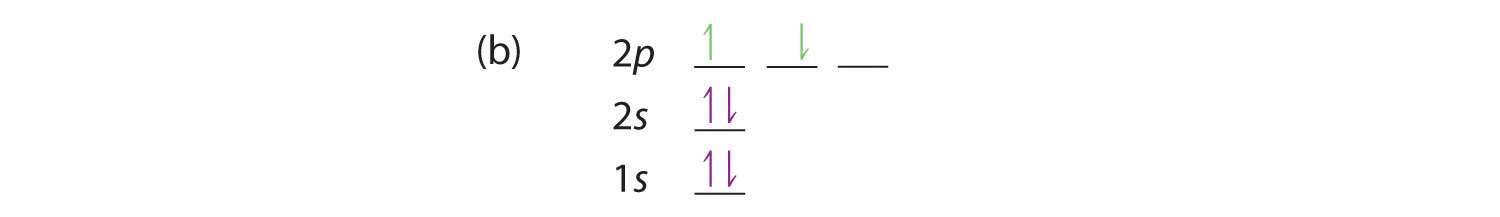

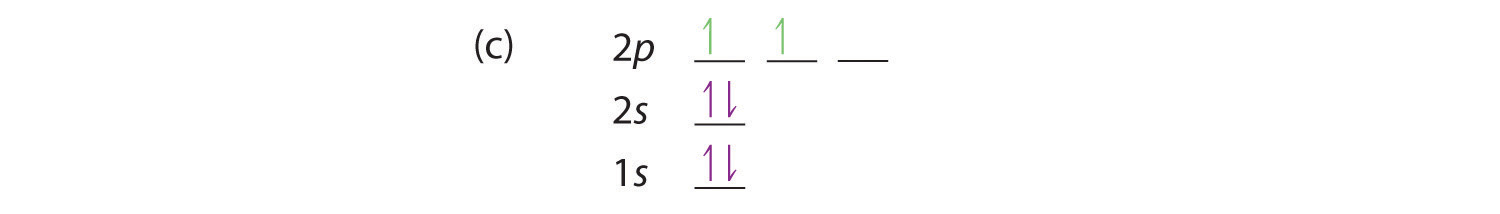

At carbon, with Z = 6 and six electrons, we are faced with a choice. Should the sixth electron be placed in the same 2p orbital that already has an electron, or should it go in one of the empty 2p orbitals? If it goes in an empty 2p orbital, will the sixth electron have its spin aligned with or be opposite to the spin of the fifth? In short, which of the following three orbital diagrams is correct for carbon, remembering that the 2p orbitals are degenerate?

Because of electron-electron interactions, it is more favorable energetically for an electron to be in an unoccupied orbital than in one that is already occupied; hence we can eliminate choice a. Similarly, experiments have shown that choice b is slightly higher in energy (less stable) than choice c because electrons in degenerate orbitals prefer to line up with their spins parallel; thus, we can eliminate choice b. Choice c illustrates Hund’s rule (named after the German physicist Friedrich H. Hund, 1896–1997), which today says that the lowest-energy electron configuration for an atom is the one that has the maximum number of electrons with parallel spins in degenerate orbitals. By Hund’s rule, the electron configuration of carbon, which is 1s22s22p2, is understood to correspond to the orbital diagram shown in c. Experimentally, it is found that the ground state of a neutral carbon atom does indeed contain two unpaired electrons.

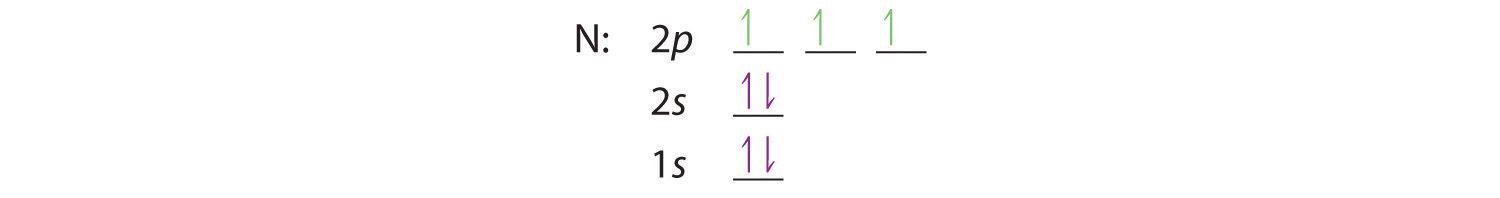

When we get to nitrogen (Z = 7, with seven electrons), Hund’s rule tells us that the lowest-energy arrangement is

with three unpaired electrons. The electron configuration of nitrogen is thus 1s22s22p3.

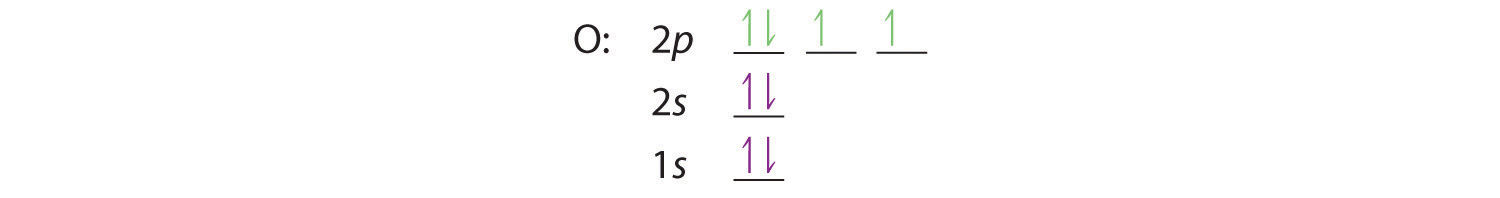

At oxygen, with Z = 8 and eight electrons, we have no choice. One electron must be paired with another in one of the 2p orbitals, which gives us two unpaired electrons and a 1s22s22p4 electron configuration. Because all the 2p orbitals are degenerate, it doesn’t matter which one has the pair of electrons.

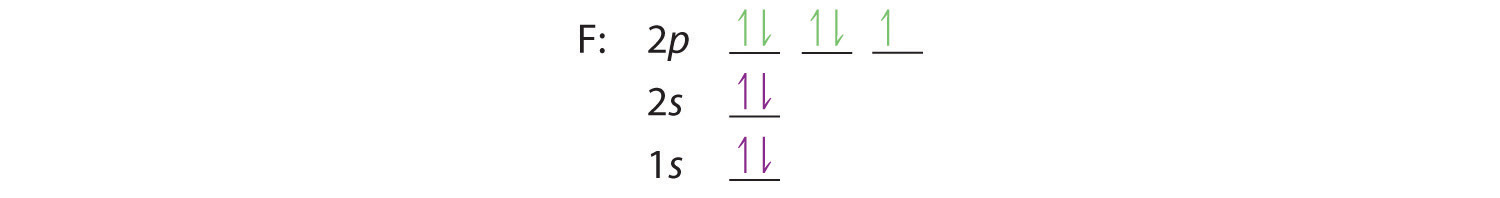

Similarly, fluorine has the electron configuration 1s22s22p5:

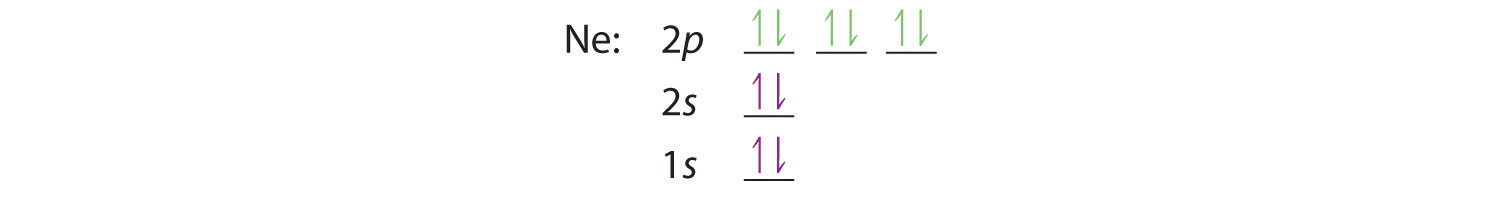

When we reach neon, with Z = 10, we have filled the 2p subshell, giving a 1s22s22p6 electron configuration:

Notice that for neon, as for helium, all the orbitals through the 2p level are completely filled. This fact is very important in dictating both the chemical reactivity and the bonding of helium and neon, as you will see.

Valence Electrons

As we continue through the periodic table in this way, writing the electron configurations of larger and larger atoms, it becomes tedious to keep copying the configurations of the filled inner subshells. In practice, chemists simplify the notation by using a bracketed noble gas symbol to represent the configuration of the noble gas from the preceding row because all the orbitals in a noble gas are filled. For example, [Ne] represents the 1s22s22p6 electron configuration of neon (Z= 10), so the electron configuration of sodium, with Z = 11, which is 1s22s22p63s1, is written as [Ne]3s1:

| Neon | Z = 10 | 1s22s22p6 |

| Sodium | Z = 11 | 1s22s22p63s1 = [Ne]3s1 |

Because electrons in filled inner orbitals are closer to the nucleus and more tightly bound to it, they are rarely involved in chemical reactions. This means that the chemistry of an atom depends mostly on the electrons in its outermost shell, which are called the valence electrons. The simplified notation allows us to see the valence-electron configuration more easily. Using this notation to compare the electron configurations of sodium and lithium, we have:

| Sodium | 1s22s22p63s1 = [Ne]3s1 |

| Lithium | 1s22s1 = [He]2s1 |

It is readily apparent that both sodium and lithium have one s electron in their valence shell. We would therefore predict that sodium and lithium have very similar chemistry, which is indeed the case.

As we continue to build the eight elements of period 3, the 3s and 3p orbitals are filled, one electron at a time. This row concludes with the noble gas argon, which has the electron configuration [Ne]3s23p6, corresponding to a filled valence shell.

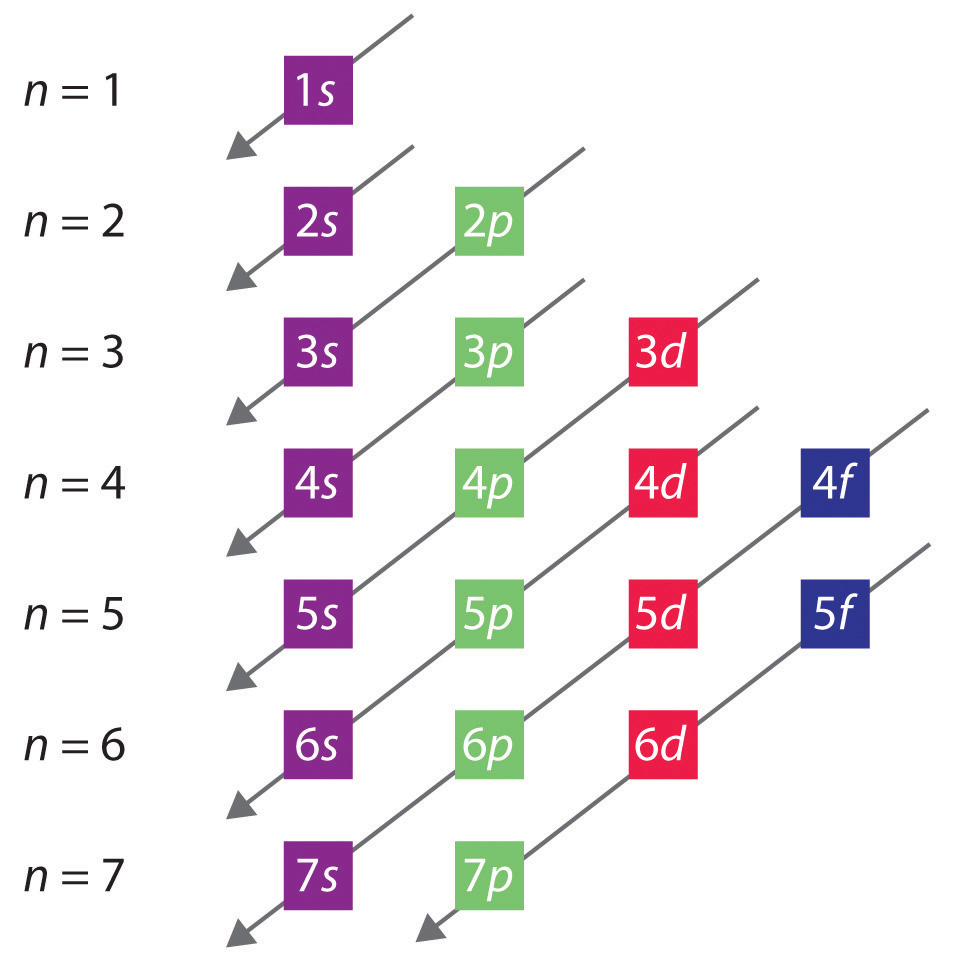

The general order in which orbitals are filled is depicted in Figure . Subshells corresponding to each value of n are written from left to right on successive horizontal lines, where each row represents a row in the periodic table. The order in which the orbitals are filled is indicated by the diagonal lines running from the upper right to the lower left. Accordingly, the 4s orbital is filled prior to the 3d orbital because of shielding and penetration effects. Consequently, the electron configuration of potassium, which begins the fourth period, is [Ar]4s1, and the configuration of calcium is [Ar]4s2. Five 3d orbitals are filled by the next 10 elements, the transition metals, followed by three 4p orbitals. Notice that the last member of this row is the noble gas krypton (Z = 36), [Ar]4s23d104p6 = [Kr], which has filled 4s, 3d, and 4p orbitals. The fifth row of the periodic table is essentially the same as the fourth, except that the 5s, 4d, and 5p orbitals are filled sequentially.

The sixth row of the periodic table will be different from the preceding two because the 4f orbitals, which can hold 14 electrons, are filled between the 6s and the 5d orbitals. The elements that contain 4f orbitals in their valence shell are the lanthanides. When the 6p orbitals are finally filled, we have reached the next noble gas, radon (Z = 86), [Xe]6s24f145d106p6 = [Rn]. In the last row, the 5f orbitals are filled between the 7s and the 6d orbitals, which gives the 14 actinide elements. Because the large number of protons makes their nuclei unstable, all the actinides are radioactive.

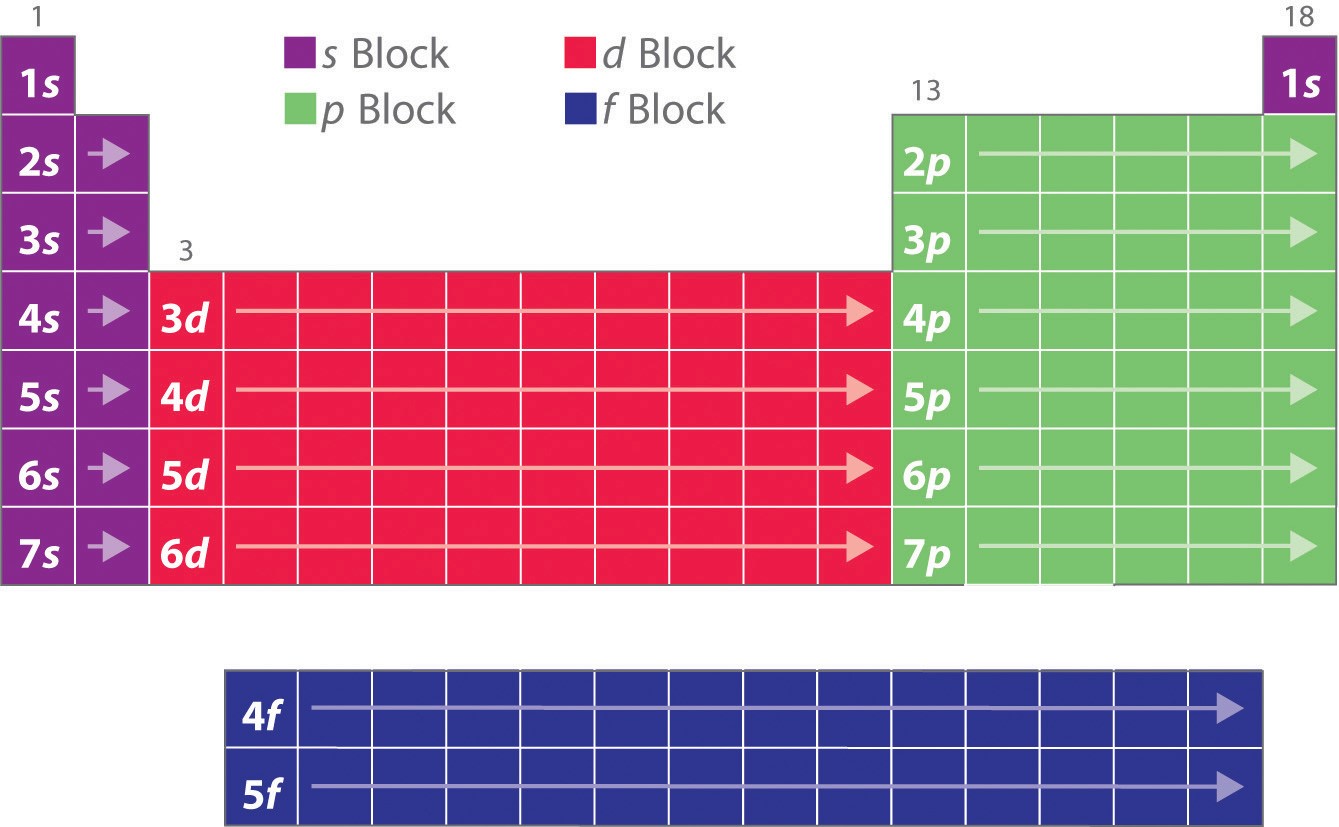

As you have learned, the electron configurations of the elements explain the otherwise peculiar shape of the periodic table. Although the table was originally organized on the basis of physical and chemical similarities between the elements within groups, these similarities are ultimately attributable to orbital energy levels and the Pauli principle, which cause the individual subshells to be filled in a particular order. As a result, the periodic table can be divided into “blocks” corresponding to the type of subshell that is being filled, as illustrated in Figure 3. For example, the two columns on the left, known as the s block, consist of elements in which the ns orbitals are being filled. The six columns on the right, elements in which the np orbitals are being filled, constitute the p block. In between are the 10 columns of the d block, elements in which the (n − 1)d orbitals are filled. At the bottom lie the 14 columns of the f block, elements in which the (n − 2)f orbitals are filled. Because two electrons can be accommodated per orbital, the number of columns in each block is the same as the maximum electron capacity of the subshell: 2 for ns, 6 for np, 10 for (n − 1)d, and 14 for (n − 2)f. Within each column, each element has the same valence electron configuration—for example, ns1 (group 1) or ns2np1 (group 13). As you will see, this is reflected in important similarities in the chemical reactivity and the bonding for the elements in each column.

Hydrogen and helium are placed somewhat arbitrarily. Although hydrogen is not an alkali metal, its 1s1 electron configuration suggests a similarity to lithium ([He]2s1) and the other elements in the first column. Although helium, with a filled ns subshell, should be similar chemically to other elements with an ns2electron configuration, the closed principal shell dominates its chemistry, justifying its placement above neon on the right.