Isotopes

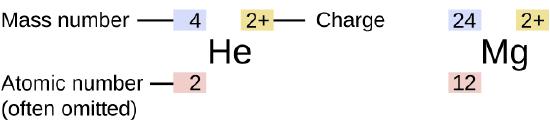

The symbol for a specific isotope of any element is written by placing the mass number as a superscript to the left of the element symbol (Figure 1). The atomic number is sometimes written as a subscript preceding the symbol, but since this number defines the element’s identity, as does its symbol, it is often omitted. For example, magnesium exists as a mixture of three isotopes, each with an atomic number of 12 and with mass numbers of 24, 25, and 26, respectively. These isotopes can be identified as 24Mg, 25Mg, and 26Mg. These isotope symbols are read as “element, mass number” and can be symbolized consistent with this reading. For instance, 24Mg is read as “magnesium 24,” and can be written as “magnesium-24” or “Mg-24.” 25Mg is read as “magnesium 25,” and can be written as “magnesium-25” or “Mg-25.” All magnesium atoms have 12 protons in their nucleus. They differ only because a 24Mg atom has 12 neutrons in its nucleus, a 25Mg atom has 13 neutrons, and a 26Mg has 14 neutrons.

Information about the naturally occurring isotopes of elements with atomic numbers 1 through 10 is given in Table 1. Note that in addition to standard names and symbols, the isotopes of hydrogen are often referred to using common names and accompanying symbols. Hydrogen-2, symbolized 2H, is also called deuterium and sometimes symbolized D. Hydrogen-3, symbolized 3H, is also called tritium and sometimes symbolized T.

| Element | Symbol | Atomic Number | Number of Protons | Number of Neutrons | Mass (amu) | % Natural Abundance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hydrogen | (protium) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1.0078 | 99.989 |

(deuterium) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2.0141 | 0.0115 | |

(tritium) | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3.01605 | — (trace) | |

| helium | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3.01603 | 0.00013 | |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 4.0026 | 100 | ||

| lithium | 3 | 3 | 3 | 6.0151 | 7.59 | |

| 3 | 3 | 4 | 7.0160 | 92.41 | ||

| beryllium | 4 | 4 | 5 | 9.0122 | 100 | |

| boron | 5 | 5 | 5 | 10.0129 | 19.9 | |

| 5 | 5 | 6 | 11.0093 | 80.1 | ||

| carbon | 6 | 6 | 6 | 12.0000 | 98.89 | |

| 6 | 6 | 7 | 13.0034 | 1.11 | ||

| 6 | 6 | 8 | 14.0032 | — (trace) | ||

| nitrogen | 7 | 7 | 7 | 14.0031 | 99.63 | |

| 7 | 7 | 8 | 15.0001 | 0.37 | ||

| oxygen | 8 | 8 | 8 | 15.9949 | 99.757 | |

| 8 | 8 | 9 | 16.9991 | 0.038 | ||

| 8 | 8 | 10 | 17.9992 | 0.205 | ||

| fluorine | 9 | 9 | 10 | 18.9984 | 100 | |

| neon | 10 | 10 | 10 | 19.9924 | 90.48 | |

| 10 | 10 | 11 | 20.9938 | 0.27 | ||

| 10 | 10 | 12 | 21.9914 | 9.25 |

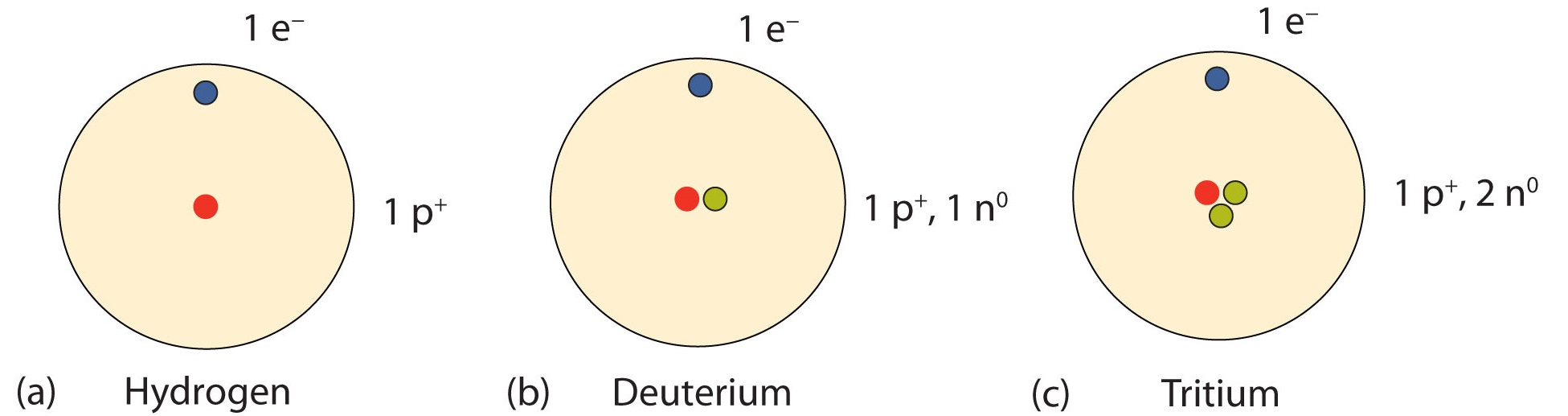

An important series of isotopes is found with hydrogen atoms. Most hydrogen atoms have a nucleus with only a single proton. About 1 in 10,000 hydrogen nuclei, however, also has a neutron; this particular isotope is called deuterium. An extremely rare hydrogen isotope, tritium, has 1 proton and 2 neutrons in its nucleus. Figure 2 compares the three isotopes of hydrogen.

Atomic Mass Unit

The atomic mass unit(u; some texts use amu, but this older style is no longer accepted) is defined as one-twelfth of the mass of a carbon-12 atom, an isotope of carbon that has six protons and six neutrons in its nucleus. By this scale, the mass of a proton is 1.00728 u, the mass of a neutron is 1.00866 u, and the mass of an electron is 0.000549 u. There will not be much error if you estimate the mass of an atom by simply counting the total number of protons and neutrons in the nucleus (i.e., identify its mass number) and ignore the electrons. Thus, the mass of carbon-12 is about 12 u, the mass of oxygen-16 is about 16 u, and the mass of uranium-238 is about 238 u. More exact masses are found in scientific references-for example, the exact mass of uranium-238 is 238.050788 u, so you can see that we are not far off by using the whole-number value as the mass of the atom.

What is the mass of an element? This is somewhat more complicated because most elements exist as a mixture of isotopes, each of which has its own mass. Thus, although it is easy to speak of the mass of an atom, when talking about the mass of an element, we must take the isotopic mixture into account.

Atomic Mass

The atomic mass of an element is a weighted average of the masses of the isotopes that compose an element. What do we mean by a weighted average? Well, consider an element that consists of two isotopes, 50% with mass 10 u and 50% with mass 11 u. A weighted average is found by multiplying each mass by its fractional occurrence (in decimal form) and then adding all the products. The sum is the weighted average and serves as the formal atomic mass of the element. In this example, we have the following:

| 0.50 × 10 u | = 5.0 u |

| 0.50 × 11 u | = 5.5 u |

| Sum | = 10.5 u = the atomic mass of our element |

Note that no atom in our hypothetical element has a mass of 10.5 u; rather, that is the average mass of the atoms, weighted by their percent occurrence.

This example is similar to a real element. Boron exists as about 20% boron-10 (five protons and five neutrons in the nuclei) and about 80% boron-11 (five protons and six neutrons in the nuclei). The atomic mass of boron is calculated similarly to what we did for our hypothetical example, but the percentages are different:

| 0.20 × 10 u | = 2.0 u |

| 0.80 × 11 u | = 8.8 u |

| Sum | = 10.8 u = the atomic mass of boron |

Thus, we use 10.8 u for the atomic mass of boron.

Virtually all elements exist as mixtures of isotopes, so atomic masses may vary significantly from whole numbers. Table 2 lists the atomic masses of some elements. The atomic masses in Table 2 are listed to three decimal places where possible, but in most cases, only one or two decimal places are needed. Note that many of the atomic masses, especially the larger ones, are not very close to whole numbers. This is, in part, the effect of an increasing number of isotopes as the atoms increase in size. (The record number is 10 isotopes for tin.)

| Element Name | Atomic Mass (u) | Element Name | Atomic Mass (u) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aluminum | 26.981 | Molybdenum | 95.94 |

| Argon | 39.948 | Neon | 20.180 |

| Arsenic | 74.922 | Nickel | 58.693 |

| Barium | 137.327 | Nitrogen | 14.007 |

| Beryllium | 9.012 | Oxygen | 15.999 |

| Bismuth | 208.980 | Palladium | 106.42 |

| Boron | 10.811 | Phosphorus | 30.974 |

| Bromine | 79.904 | Platinum | 195.084 |

| Calcium | 40.078 | Potassium | 39.098 |

| Carbon | 12.011 | Radium | n/a |

| Chlorine | 35.453 | Radon | n/a |

| Cobalt | 58.933 | Rubidium | 85.468 |

| Copper | 63.546 | Scandium | 44.956 |

| Fluorine | 18.998 | Selenium | 78.96 |

| Gallium | 69.723 | Silicon | 28.086 |

| Germanium | 72.64 | Silver | 107.868 |

| Gold | 196.967 | Sodium | 22.990 |

| Helium | 4.003 | Strontium | 87.62 |

| Hydrogen | 1.008 | Sulfur | 32.065 |

| Iodine | 126.904 | Tantalum | 180.948 |

| Iridium | 192.217 | Tin | 118.710 |

| Iron | 55.845 | Titanium | 47.867 |

| Krypton | 83.798 | Tungsten | 183.84 |

| Lead | 207.2 | Uranium | 238.029 |

| Lithium | 6.941 | Xenon | 131.293 |

| Magnesium | 24.305 | Zinc | 65.409 |

| Manganese | 54.938 | Zirconium | 91.224 |

| Mercury | 200.59 | Molybdenum | 95.94 |

| Note: Atomic mass is given to three decimal places, if known. | |||

Molecular Mass

Now that we understand that atoms have mass, it is easy to extend the concept to the mass of molecules. The molecular mass is the sum of the masses of the atoms in a molecule. This may seem like a trivial extension of the concept, but it is important to count the number of each type of atom in the molecular formula. Also, although each atom in a molecule is a particular isotope, we use the weighted average, or atomic mass, for each atom in the molecule.

For example, if we were to determine the molecular mass of dinitrogen trioxide, N2O3, we would need to add the atomic mass of nitrogen two times with the atomic mass of oxygen three times:

| 2 N masses = 2 × 14.007 u | = 28.014 u |

| 3 O masses = 3 × 15.999 u | = 47.997 u |

| Total | = 76.011 u = the molecular mass of N2O3 |

We would not be far off if we limited our numbers to one or even two decimal places.

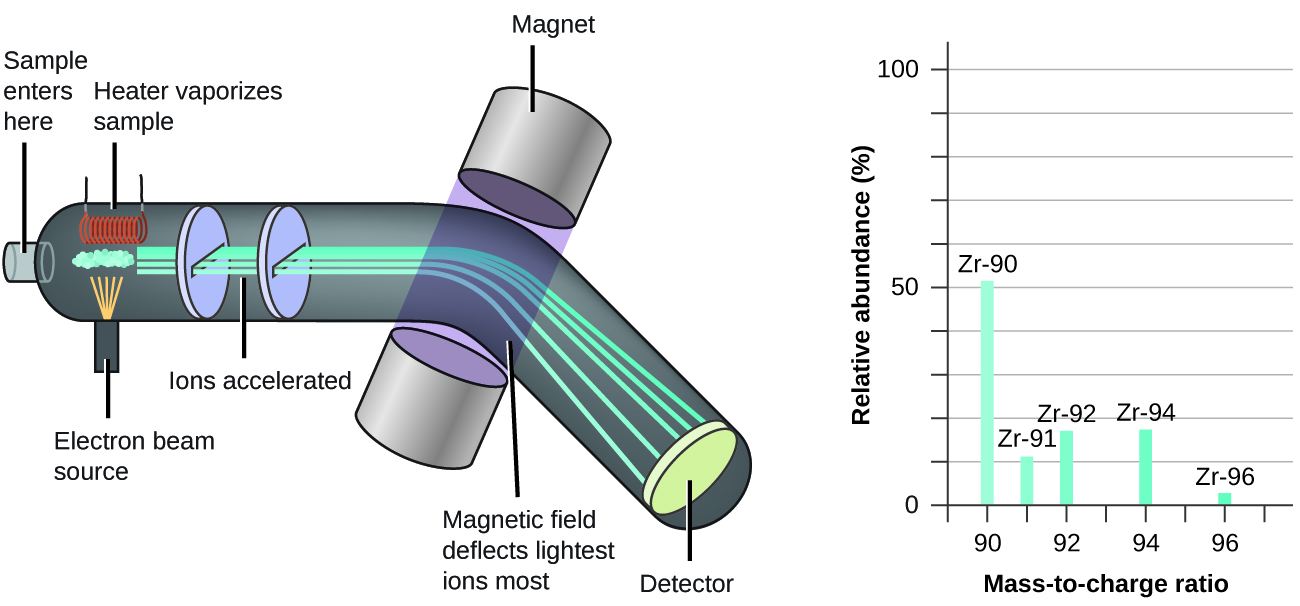

The occurrence and natural abundances of isotopes can be experimentally determined using an instrument called a mass spectrometer. Mass spectrometry (MS) is widely used in chemistry, forensics, medicine, environmental science, and many other fields to analyze and help identify the substances in a sample of material. In a typical mass spectrometer (Figure 3), the sample is vaporized and exposed to a high-energy electron beam that causes the sample’s atoms (or molecules) to become electrically charged, typically by losing one or more electrons. These cations then pass through a (variable) electric or magnetic field that deflects each cation’s path to an extent that depends on both its mass and charge (similar to how the path of a large steel ball bearing rolling past a magnet is deflected to a lesser extent that that of a small steel BB). The ions are detected, and a plot of the relative number of ions generated versus their mass-to-charge ratios (a mass spectrum) is made. The height of each vertical feature or peak in a mass spectrum is proportional to the fraction of cations with the specified mass-to-charge ratio. Since its initial use during the development of modern atomic theory, MS has evolved to become a powerful tool for chemical analysis in a wide range of applications.

APPLICATIONS OF ISOTOPES

During the Manhattan project, the majority of federal funding was dedicated the separation of uranium isotopes. The two most common isotopes of uranium are U-238 and U-235. About 99.3% of uranium is of the U-238 variety, this form is not fissionable and will not work in a nuclear weapon or reaction. The remaining .7% is U-235 which is fissionable, but first had to be separated from U-238. This separation process is called enrichment. During World War II, a nuclear facility was built in Oak Ridge, Tennessee to accomplish this project. At the time, the enrichment process only produced enough U-235 for one nuclear weapon. This fuel was placed inside the smaller of the two atomic bombs (Little Boy) dropped over Japan.

Figure 4: A billet of highly enriched uranium that was recovered from scrap processed at the Y-12 National Security Complex Plant. Original and unrotated.

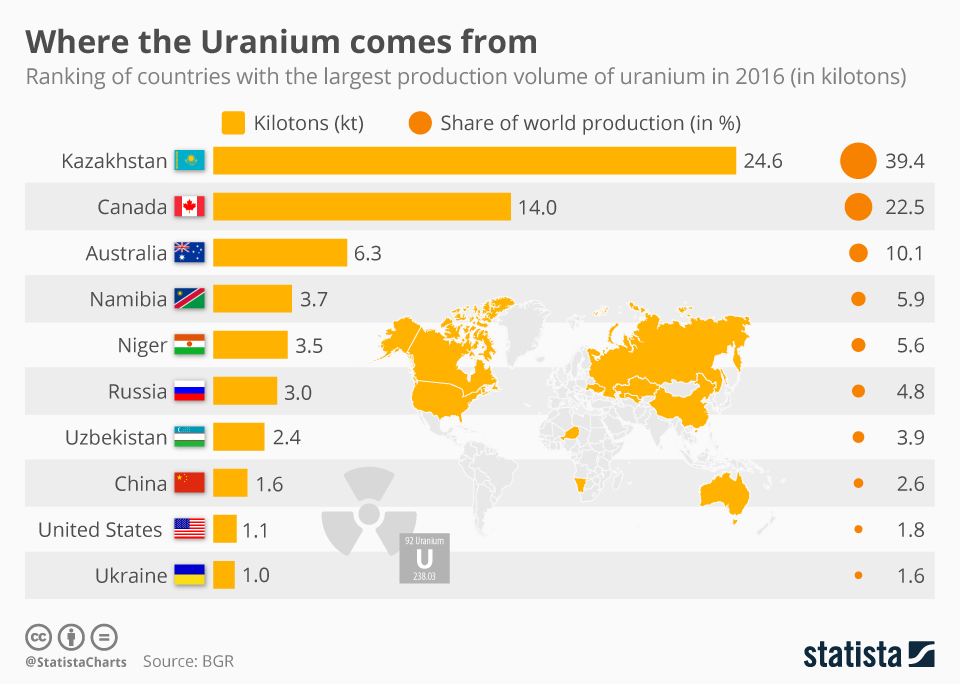

Uranium is a natural element that can be found in several different countries. Countries that do not have natural uranium supplies would need to obtain it from one of the countries below. Most nuclear reactors that provide energy rely on U-235 as a source of fuel. Fortunately, reactors only need 2-5% U-235 for the production of megawatts or even gigawatts of power. If the purification process exceeds this level, than it is likely a country is focusing on making nuclear weapons. For example, Manhattan Project scientists enriched U-235 up to 90% in order to produce the Little Boy weapon.

Abbreviations like HEU (highly enriched uranium) and LEU (low-enriched uranium) are used frequently by nuclear scientists and groups. HEU is defined as being over 20% pure U-235 and would not be used in most commercial nuclear reactors. This type of material is used to fuel larger submarines and aircraft carriers. If the purification of U-235 reaches 90%, then the HEU is further classified as being weapons grade material. This type of U-235 could be used to make a nuclear weapon (fission or even fusion based). As for LEU, its U-235 level would be below this 20% mark. LEU would be used for commercial nuclear reactors and smaller, nuclear powered submarines. LEU is not pure enough to be used in a conventional nuclear weapon, but could be used in a dirty bomb. This type of weapon uses conventional explosives like dynamite to spread nuclear material. Unlike a nuclear weapon, dirty bombs are not powerful enough to affect large groups of buildings or people. Unfortunately, the spread of nuclear material would cause massive chaos for a community and would result in casualties.

Summary

Isotopes of an element are atoms with the same atomic number but different mass numbers; isotopes of an element, therefore, differ from each other only in the number of neutrons within the nucleus. When a naturally occurring element is composed of several isotopes, the atomic mass of the element represents the average of the masses of the isotopes involved. A chemical symbol identifies the atoms in a substance using symbols, which are one-, two-, or three-letter abbreviations for the atoms.