So far in our valence bond orbital descriptions we have not dealt with polyatomic systems with multiple bonds. To do so, we can use an approach in which we describe bonding using localized electron-pair bonds formed by hybrid atomic orbitals, and bonding using molecular orbitals formed by unhybridized npatomic orbitals.

Multiple Bonding

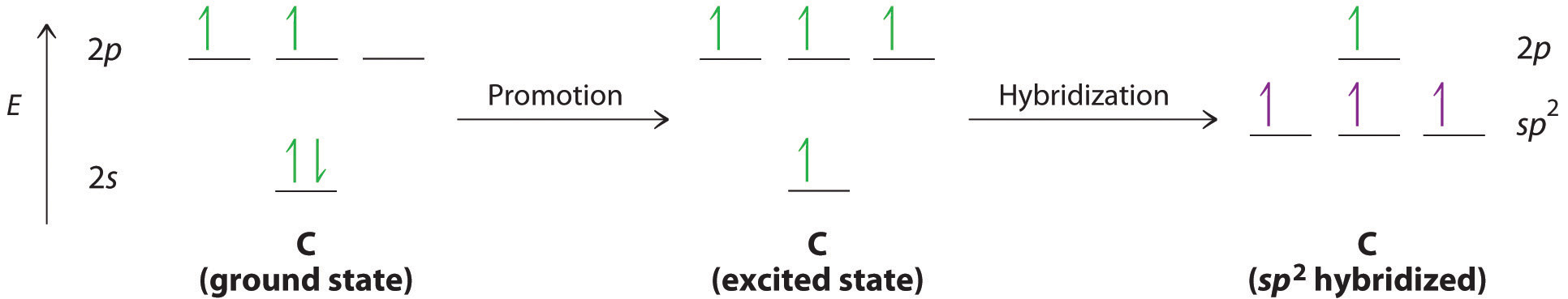

We begin our discussion by considering the bonding in ethylene (C2H4). Experimentally, we know that the H–C–H and H–C–C angles in ethylene are approximately 120°. This angle suggests that the carbon atoms are sp2 hybridized, which means that a singly occupied sp2 orbital on one carbon overlaps with a singly occupied s orbital on each H and a singly occupied sp2 lobe on the other C. The sp2 hybridization can be represented as follows:

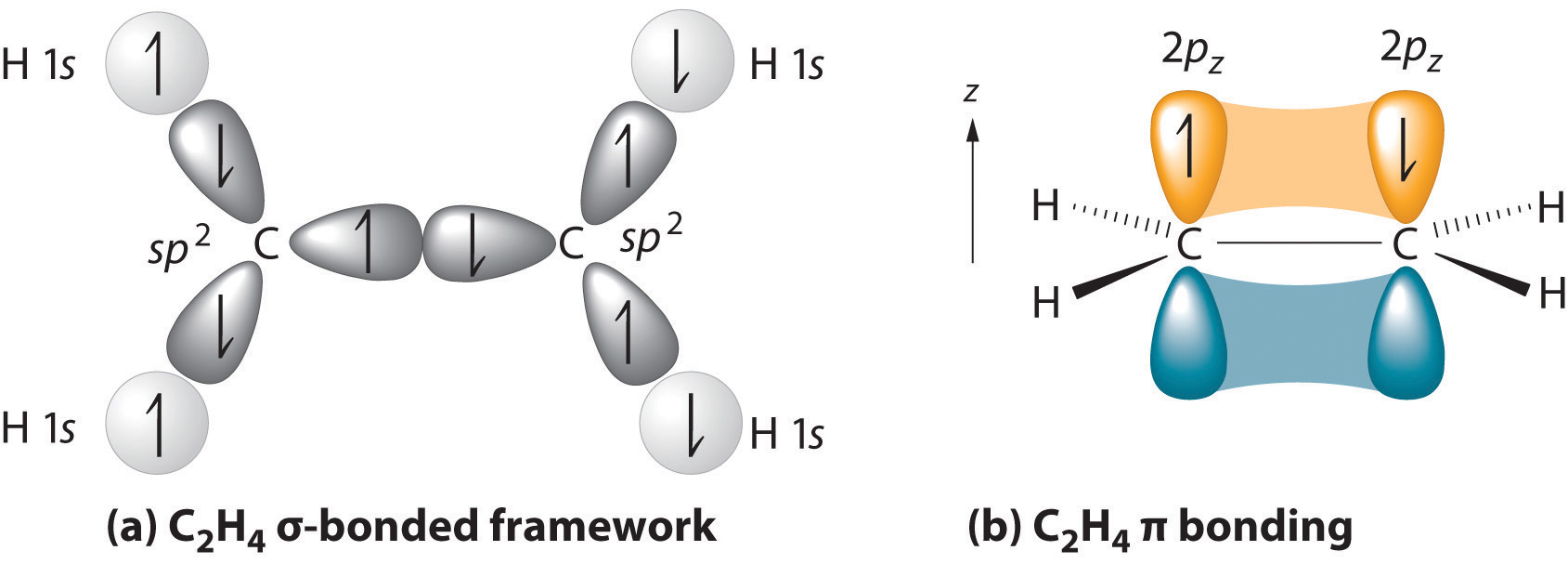

With this hybridization, each carbon forms a trigonal planar set of three bonds: two C–H (sp2 + s) and one C–C (sp2 + sp2) (part (a) in Figure ). After hybridization, however, each carbon still has one unhybridized 2pz orbital that is perpendicular to the hybridized lobes and contains a single electron (part (b) in Figure ). These two singly occupied 2pz orbitals can overlap in a side-to-side fashion to form a bond. The orbitals overlap both above and below the plane of the molecule but form just one bonding orbital space. The C–C bond plus the hybridized C–C bond together form a double bond.

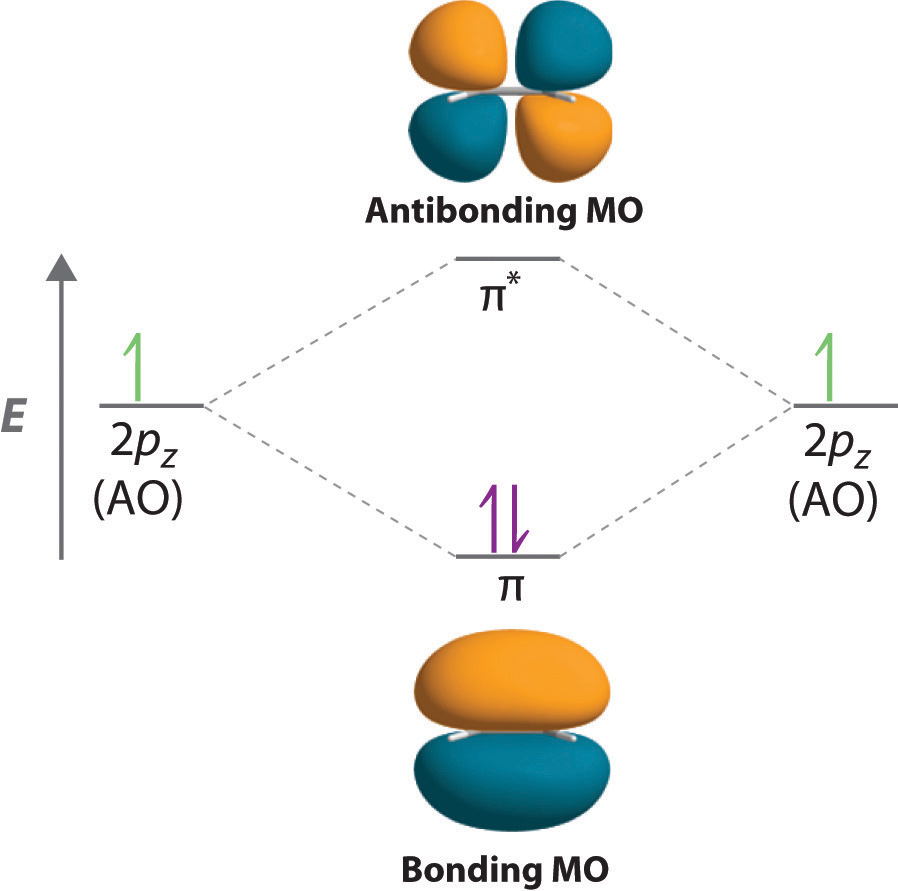

When considering multiple bonds, we can introduce the more sophisticated molecular orbital theory to better understand how orbital overlap creates bonding orbitals. Recall that atomic orbitals represent electron wavefunctions; this implies that "orbital overlap" actually involves the combination of those wavefunctions, which can occur via both constructive and destructive interference. Thus, when the two singly occupied 2pz orbitals in ethylene overlap, they actually create both a bonding orbital (constructive combination) and a * antibonding orbital (destructive combination), which produces the energy-level diagram shown in Figure . With the formation of a bonding orbital, electron density increases in the plane between the carbon nuclei. Electrons occupying this orbital lower the potential energy of the combination and tend to hold the two nuclei together (i.e., they form a bond.) The * orbital lies outside the internuclear region and has a nodal plane perpendicular to the internuclear axis; electrons in this orbital would tend to push the nuclei apart, so it is called an antibonding orbital. Because each 2pz orbital has a single electron, there are only two electrons, enough to fill only the bonding () level, leaving the * orbital empty. Consequently, the C–C bond in ethylene consists of a bond and a bond, which together give a C=C double bond. Our model is supported by the facts that the measured carbon–carbon bond is shorter than that in ethane (133.9 pm versus 153.5 pm) and the bond is stronger (728 kJ/mol versus 376 kJ/mol in ethane). The two CH2fragments are coplanar, which maximizes the overlap of the two singly occupied 2pz orbitals.

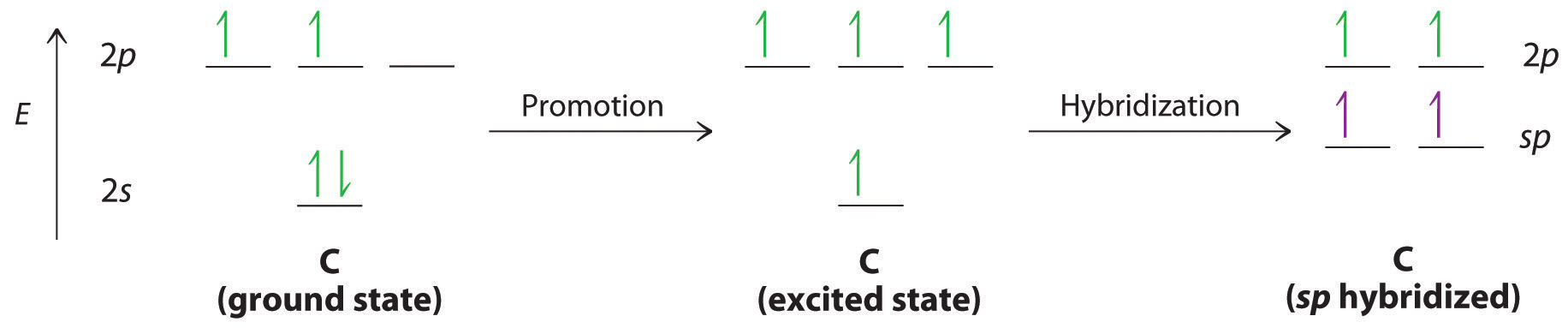

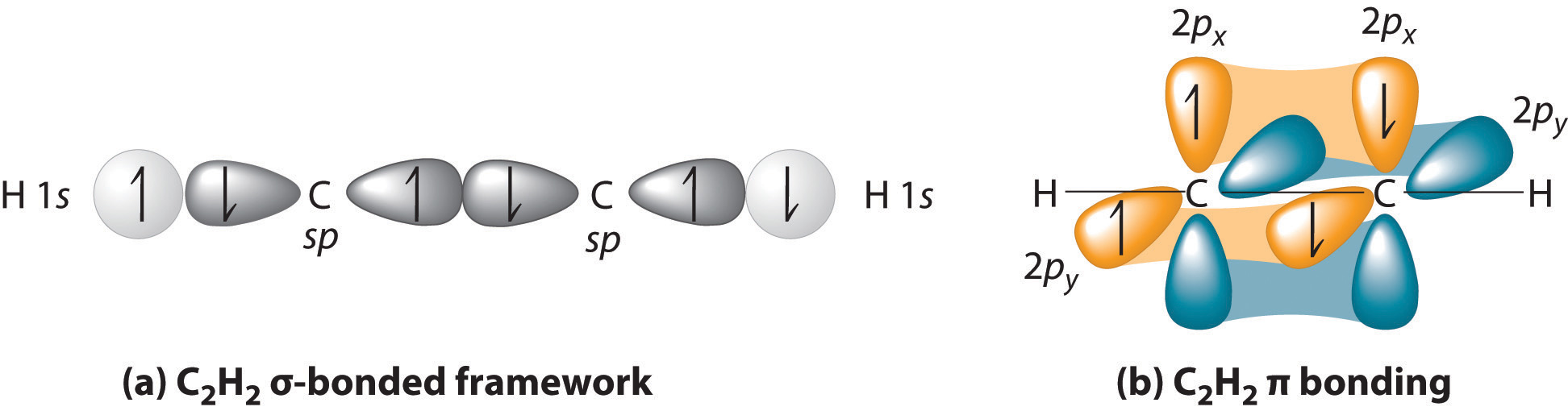

Triple bonds, as in acetylene (C2H2), can also be explained using a combination of hybrid atomic orbitals and molecular orbitals. The four atoms of acetylene are collinear, which suggests that each carbon is sp hybridized. If one sp lobe on each carbon atom is used to form a C–C bond and one is used to form the C–H bond, then each carbon will still have two unhybridized 2p orbitals (a 2px,y pair), each with one electron (part (a) in Figure 3)

The two 2p orbitals on each carbon can align with the corresponding 2p orbitals on the adjacent carbon to simultaneously form a pair of bonds (part (b) in Figure ). Because each of the unhybridized 2p orbitals has a single electron, four electrons are available for bonding, which is enough to occupy only the bonding molecular orbitals. Acetylene must therefore have a carbon–carbon triple bond, which consists of a C–C bond and two mutually perpendicular bonds. Acetylene does in fact have a shorter carbon–carbon bond (120.3 pm) and a higher bond energy (965 kJ/mol) than ethane and ethylene, as we would expect for a triple bond.

In complex molecules, hybrid orbitals and valence bond theory can be used to describe bonding, and unhybridized orbitals and molecular orbital theory can be used to describe bonding.

Molecular Orbitals and Resonance Structures

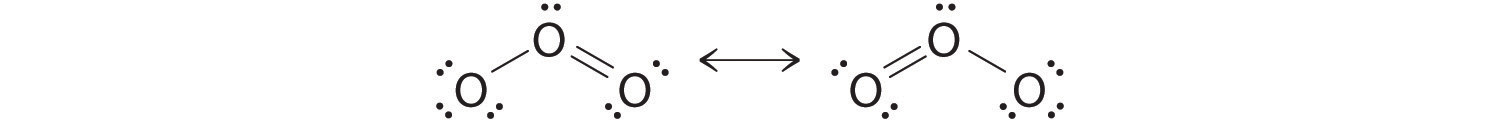

Resonance structures can be used to describe the bonding in molecules such as ozone (O3) and the nitrite ion (NO2−). Ozone can be represented by either of these Lewis electron structures:

Although the VSEPR model correctly predicts that both species are bent, it gives no information about their bond orders.

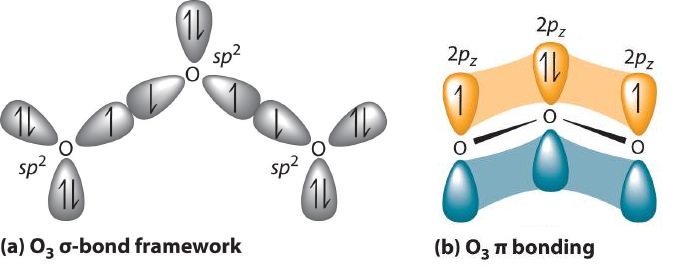

Experimental evidence indicates that ozone has a bond angle of 117.5°. Because this angle is close to 120°, it is likely that the central oxygen atom in ozone is trigonal planar and sp2 hybridized. If we assume that the terminal oxygen atoms are also sp2 hybridized, then we obtain the -bonded framework shown in Figure . Two of the three sp2 lobes on the central O are used to form O–O sigma bonds, and the third has a lone pair of electrons. Each terminal oxygen atom has two lone pairs of electrons that are also in sp2 lobes. In addition, each oxygen atom has one unhybridized 2p orbital perpendicular to the molecular plane. The bonds and lone pairs account for a total of 14 electrons (five lone pairs and two bonds, each containing 2 electrons). Each oxygen atom in ozone has 6 valence electrons, so O3 has a total of 18 valence electrons. Subtracting 14 electrons from the total gives us 4 electrons that must occupy the three unhybridized 2p orbitals.

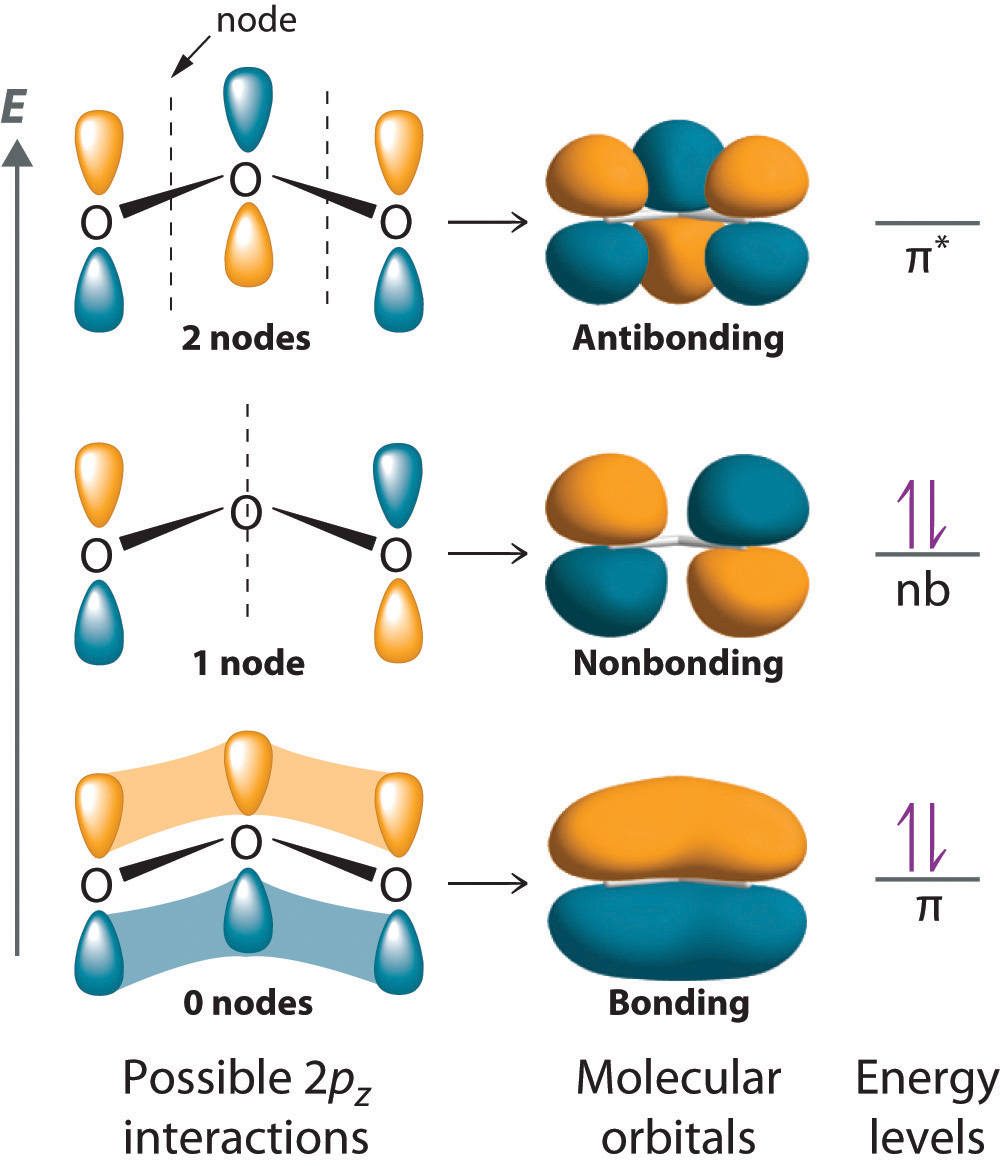

With a molecular orbital approach to describe the bonding, three 2p atomic orbitals give us three molecular orbitals, as shown in Figure . One of the molecular orbitals is a bonding molecular orbital, which is shown as a banana-shaped region of electron density above and below the molecular plane. This region has no nodes perpendicular to the O3 plane. The molecular orbital with the highest energy has two nodes that bisect the O–O bonds; it is a * antibonding orbital. The third molecular orbital contains a single node that is perpendicular to the O3 plane and passes through the central O atom; because the orbital nodes do not directly touch, this is a nonbonding molecular orbital. Because electrons in nonbonding orbitals are neither bonding nor antibonding, they are ignored in calculating bond orders.

We can now place the remaining four electrons in the three energy levels shown in Figure , thereby filling the bonding and the nonbonding levels. The result is a single bond holding three oxygen atoms together, or bond per O–O. We therefore predict the overall O–O bond order to be bond plus 1 bond), just as predicted using resonance structures. The molecular orbital description, however, makes it more clear that resonance really means that electrons are delocalized over all three atoms at once. The molecular orbital approach also shows that the nonbonding orbital is localized on the terminal O atoms, which suggests that they are more electron rich than the central O atom (corresponding to the "extra" lone pair seen on one of the terminal O atoms in the Lewis resonance structures). The reactivity of ozone is consistent with the predicted charge localization.

Resonance structures are a crude way of describing molecular orbitals that extend over more than two atoms.

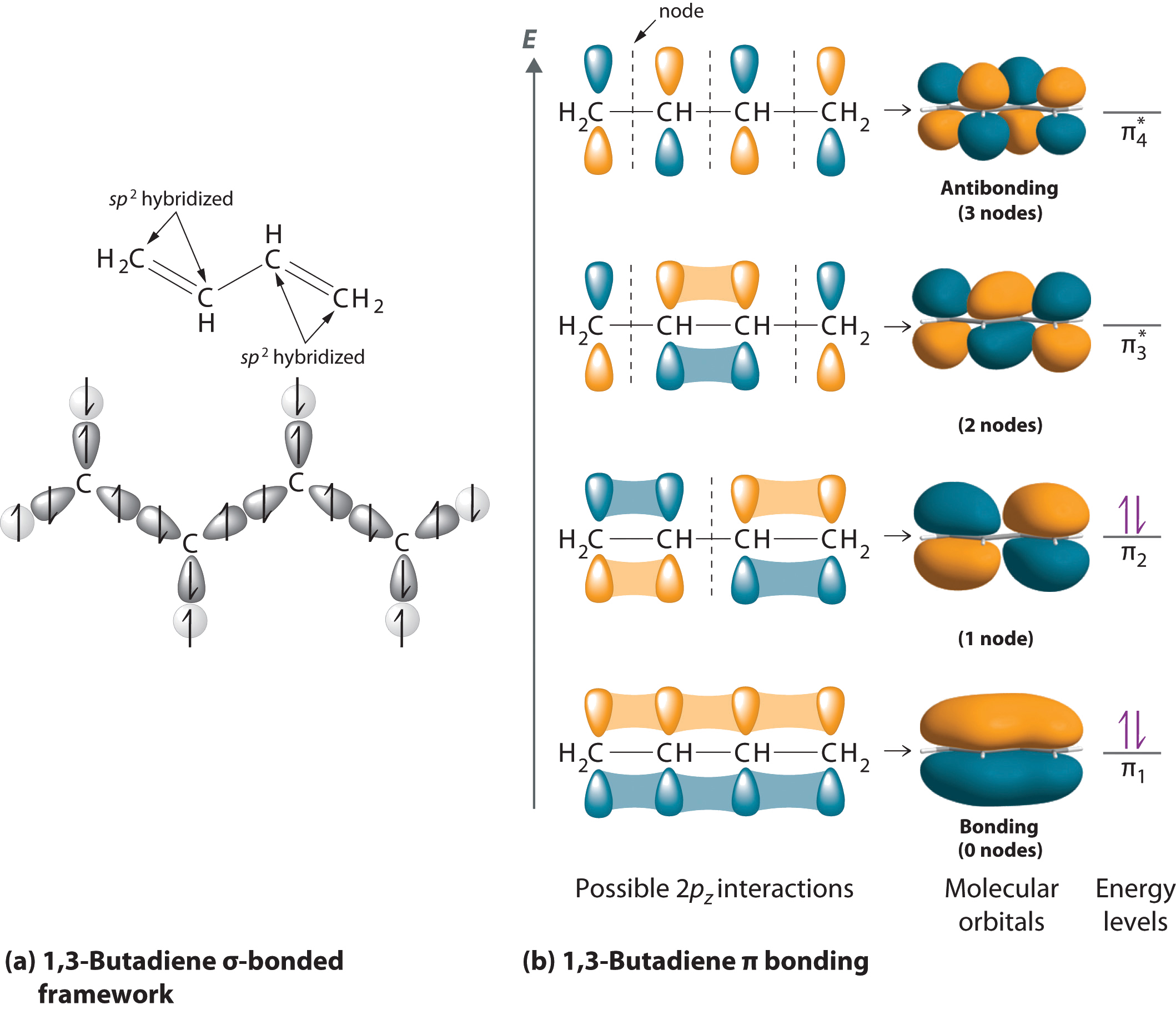

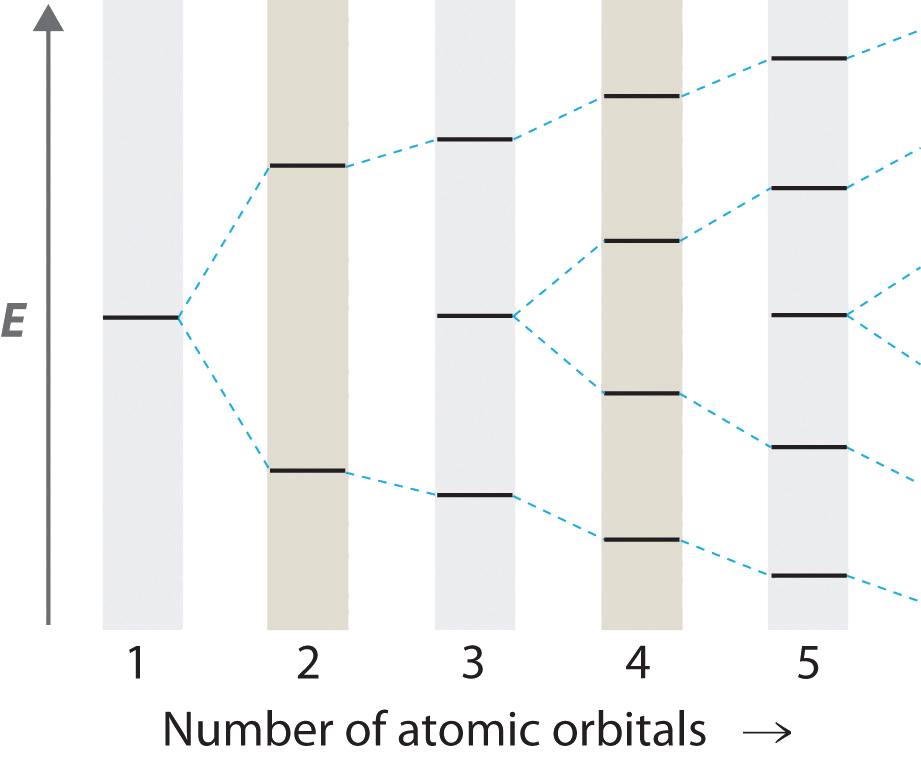

THE CHEMISTRY OF VISION

Hydrocarbons in which two or more carbon–carbon double bonds are directly linked by carbon–carbon single bonds (called conjugated structures) are generally more stable than expected because of resonance. Because the double bonds are close enough to interact electronically with one another, the electrons are shared over all the carbon atoms, as illustrated for 1,3-butadiene in Figure . As the number of interacting atomic orbitals increases, the number of molecular orbitals increases, the energy spacing between molecular orbitals decreases, and the systems become more stable (Figure ). Thus as a chain of alternating double and single bonds becomes longer, the energy required to excite an electron from the highest-energy occupied (bonding) orbital to the lowest-energy unoccupied (antibonding) orbital decreases. If the chain is long enough, the amount of energy required to excite an electron corresponds to the energy of visible light. For example, vitamin A is yellow because its chain of five alternating double bonds is able to absorb violet light. Many of the colors we associate with dyes result from this same phenomenon; most dyes are organic compounds with alternating double bonds.

As the number of atomic orbitals increases, the difference in energy between the resulting molecular orbital energy levels decreases, which allows light of lower energy to be absorbed. As a result, organic compounds with long chains of carbon atoms and alternating single and double bonds tend to become more deeply colored as the number of double bonds increases.

As the number of interacting atomic orbitals increases, the energy separation between the resulting molecular orbitals steadily decreases.

A derivative of vitamin A called retinal is used by the human eye to detect light and has a structure with alternating C=C double bonds. When visible light strikes retinal, the energy separation between the molecular orbitals is sufficiently close that the energy absorbed corresponds to the energy required to change one double bond in the molecule from cis, where like groups are on the same side of the double bond, to trans, where they are on opposite sides, initiating a process that causes a signal to be sent to the brain. If this mechanism is defective, we lose our vision in dim light. Once again, a molecular orbital approach to bonding explains a process that cannot be explained using any of the other approaches we have described.

Summary

Polyatomic systems with multiple bonds can be described using hybrid atomic orbitals for bonding and molecular orbitals to describe bonding. To describe the bonding in more complex molecules with multiple bonds, we can use an approach that uses hybrid atomic orbitals to describe the bonding and molecular orbitals to describe the bonding. In this approach, unhybridized np orbitals on atoms bonded to one another are allowed to interact to produce bonding, antibonding, or nonbonding combinations. For bonds between two atoms (as in ethylene or acetylene), the resulting molecular orbitals are virtually identical to the molecular orbitals in diatomic molecules such as O2 and N2. Applying the same approach to bonding between three or four atoms requires combining three or four unhybridized np orbitals on adjacent atoms to generate bonding, antibonding, and nonbonding molecular orbitals extending over all of the atoms. Filling the resulting energy-level diagram with the appropriate number of electrons explains the bonding in molecules or ions that previously required the use of resonance structures in the Lewis electron-pair approach.