Heat Capacity

We now introduce two concepts useful in describing heat flow and temperature change. The heat capacity () of a body of matter is the quantity of heat () it absorbs or releases when it experiences a temperature change () of 1 degree Celsius (or equivalently, 1 kelvin)

Heat capacity is determined by both the type and amount of substance that absorbs or releases heat. It is therefore an extensive property—its value is proportional to the amount of the substance.

For example, consider the heat capacities of two cast iron frying pans. The heat capacity of the large pan is five times greater than that of the small pan because, although both are made of the same material, the mass of the large pan is five times greater than the mass of the small pan. More mass means more atoms are present in the larger pan, so it takes more energy to make all of those atoms vibrate faster. The heat capacity of the small cast iron frying pan is found by observing that it takes 18,140 J of energy to raise the temperature of the pan by 50.0 °C

The larger cast iron frying pan, while made of the same substance, requires 90,700 J of energy to raise its temperature by 50.0 °C. The larger pan has a (proportionally) larger heat capacity because the larger amount of material requires a (proportionally) larger amount of energy to yield the same temperature change:

The specific heat capacity () of a substance, commonly called its specific heat, is the quantity of heat required to raise the temperature of 1 gram of a substance by 1 degree Celsius (or 1 kelvin):

Specific heat capacity depends only on the kind of substance absorbing or releasing heat. It is an intensive property—the type, but not the amount, of the substance is all that matters. For example, the small cast iron frying pan has a mass of 808 g. The specific heat of iron (the material used to make the pan) is therefore:

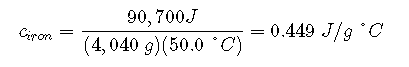

The large frying pan has a mass of 4040 g. Using the data for this pan, we can also calculate the specific heat of iron:

Although the large pan is more massive than the small pan, since both are made of the same material, they both yield the same value for specific heat (for the material of construction, iron). Note that specific heat is measured in units of energy per temperature per mass and is an intensive property, being derived from a ratio of two extensive properties (heat and mass). The molar heat capacity, also an intensive property, is the heat capacity per mole of a particular substance and has units of J/mol °C (Figure ).

The heat capacity of an object depends on both its mass and its composition. For example, doubling the mass of an object doubles its heat capacity. Consequently, the amount of substance must be indicated when the heat capacity of the substance is reported. The molar heat capacity (Cp) is the amount of energy needed to increase the temperature of 1 mol of a substance by 1°C; the units of Cp are thus J/(mol•°C).The subscript p indicates that the value was measured at constant pressure. The specific heat () is the amount of energy needed to increase the temperature of 1 g of a substance by 1°C; its units are thus J/(g•°C).

We can relate the quantity of a substance, the amount of heat transferred, its heat capacity, and the temperature change either via moles or mass:

where

is the number of moles of substance and

is the molar heat capacity (i.e., heat capacity per mole of substance), and

is the temperature change.

where

is the mass of substance in grams,

is the specific heat (i.e., heat capacity per gram of substance), and

Both Equations are under constant pressure (which matters) and both show that we know the amount of a substance and its specific heat (for mass) or molar heat capcity (for moles), we can determine the amount of heat, , entering or leaving the substance by measuring the temperature change before and after the heat is gained or lost.

The specific heats of some common substances are given in Table . Note that the specific heat values of most solids are less than 1 J/(g•°C), whereas those of most liquids are about 2 J/(g•°C). Water in its solid and liquid states is an exception. The heat capacity of ice is twice as high as that of most solids; the heat capacity of liquid water, 4.184 J/(g•°C), is one of the highest known. The specific heat of a substance varies somewhat with temperature. However, this variation is usually small enough that we will treat specific heat as constant over the range of temperatures that will be considered in this chapter. Specific heats of some common substances are listed in Table .

| Substance | Symbol (state) | Specific Heat (J/g °C) |

|---|---|---|

| helium | He(g) | 5.193 |

| water | H2O(l) | 4.184 |

| ethanol | C2H6O(l) | 2.376 |

| ice | H2O(s) | 2.093 (at −10 °C) |

| water vapor | H2O(g) | 1.864 |

| nitrogen | N2(g) | 1.040 |

| air | mixture | 1.007 |

| oxygen | O2(g) | 0.918 |

| aluminum | Al(s) | 0.897 |

| carbon dioxide | CO2(g) | 0.853 |

| argon | Ar(g) | 0.522 |

| iron | Fe(s) | 0.449 |

| copper | Cu(s) | 0.385 |

| lead | Pb(s) | 0.130 |

| gold | Au(s) | 0.129 |

| silicon | Si(s) | 0.712 |

| quartz | 0.730 |

The value of is intrinsically a positive number, but and can be either positive or negative, and they both must have the same sign. If and are positive, then heat flows from the surroundings into an object. If and are negative, then heat flows from an object into its surroundings.

If a substance gains thermal energy, its temperature increases, its final temperature is higher than its initial temperature, then and is positive. If a substance loses thermal energy, its temperature decreases, the final temperature is lower than the initial temperature, so and is negative.

Note that the relationship between heat, specific heat, mass, and temperature change can be used to determine any of these quantities (not just heat) if the other three are known or can be deduced.

Heat "Flow" to Thermal Equilibrium

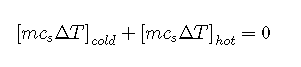

When two objects at different temperatures are placed in contact, heat flows from the warmer object to the cooler one until the temperature of both objects is the same. The law of conservation of energy says that the total energy cannot change during this process:

The equation implies that the amount of heat that flows from a warmer object is the same as the amount of heat that flows into a cooler object. Because the direction of heat flow is opposite for the two objects, the sign of the heat flow values must be opposite:

Thus heat is conserved in any such process, consistent with the law of conservation of energy.

The amount of heat lost by a warmer object equals the amount of heat gained by a cooler object.

Substituting for from Equation gives

which can be rearranged to give

When two objects initially at different temperatures are placed in contact, we can use Equation to calculate the final temperature if we know the chemical composition and mass of the objects.