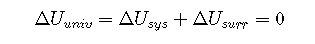

The relationship between the energy change of a system and that of its surroundings is given by the first law of thermodynamics, which states that the energy of the universe is constant. We can express this law mathematically as follows:

or

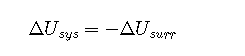

where the subscripts univ, sys, and surr refer to the universe, the system, and the surroundings, respectively. Thus the change in energy of a system is identical in magnitude but opposite in sign to the change in energy of its surroundings.

The tendency of all systems, chemical or otherwise, is to move toward the state with the lowest possible energy.

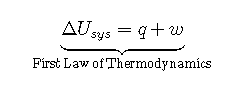

An important factor that determines the outcome of a chemical reaction is the tendency of all systems, chemical or otherwise, to move toward the lowest possible overall energy state. As a brick dropped from a rooftop falls, its potential energy is converted to kinetic energy; when it reaches ground level, it has achieved a state of lower potential energy. Anyone nearby will notice that energy is transferred to the surroundings as the noise of the impact reverberates and the dust rises when the brick hits the ground. Similarly, if a spark ignites a mixture of isooctane and oxygen in an internal combustion engine, carbon dioxide and water form spontaneously, while potential energy (in the form of the relative positions of atoms in the molecules) is released to the surroundings as heat and work. The internal energy content of the product mixture is less than that of the isooctane reactant mixture. The two cases differ, however, in the form in which the energy is released to the surroundings. In the case of the falling brick, the energy is transferred as work done on whatever happens to be in the path of the brick; in the case of burning isooctane, the energy can be released as solely heat (if the reaction is carried out in an open container) or as a mixture of heat and work (if the reaction is carried out in the cylinder of an internal combustion engine). Because heat and work are the only two ways in which energy can be transferred between a system and its surroundings, any change in the internal energy of the system is the sum of the heat transferred () and the work done ():

Although and are not state functions on their own, their sum () is independent of the path taken and is therefore a state function. A major task for the designers of any machine that converts energy to work is to maximize the amount of work obtained and minimize the amount of energy released to the environment as heat. An example is the combustion of coal to produce electricity. Although the maximum amount of energy available from the process is fixed by the energy content of the reactants and the products, the fraction of that energy that can be used to perform useful work is not fixed. Because we focus almost exclusively on the changes in the energy of a system, we will not use “sys” as a subscript unless we need to distinguish explicitly between a system and its surroundings.

Although and are not state functions, their sum () is independent of the path taken and therefore is a difference of a state function.

By convention, both heat flow and work have a negative sign when energy is transferred from a system to its surroundings and vice versa.

Summary

The first law of thermodynamics states that the energy of the universe is constant. The change in the internal energy of a system is the sum of the heat transferred and the work done. The heat flow is equal to the change in the internal energy of the system plus the work done. When the volume of a system is constant, changes in its internal energy can be calculated by substituting the ideal gas law into the equation for .