When we study energy changes in chemical reactions, the most important quantity is usually the enthalpy of reaction (), the change in enthalpy that occurs during a reaction (such as the dissolution of a piece of copper in nitric acid). If heat flows from a system to its surroundings, the enthalpy of the system decreases, so is negative. Conversely, if heat flows from the surroundings to a system, the enthalpy of the system increases, so is positive. Thus for an exothermic reaction, and for an endothermic reaction. In chemical reactions, bond breaking requires an input of energy and is therefore an endothermic process, whereas bond making releases energy, which is an exothermic process. The sign conventions for heat flow and enthalpy changes are summarized in the following table:

| Reaction Type | q | |

|---|---|---|

| exothermic | < 0 | < 0 (heat flows from a system to its surroundings) |

| endothermic | > 0 | > 0 (heat flows from the surroundings to a system) |

If is negative, then the enthalpy of the products is less than the enthalpy of the reactants; that is, an exothermic reaction is energetically downhill (Figure ). Conversely, if is positive, then the enthalpy of the products is greater than the enthalpy of the reactants; thus, an endothermic reaction is energetically uphill (Figure ). Two important characteristics of enthalpy and changes in enthalpy are summarized in the following discussion.

Bond breaking ALWAYS requires an input of energy; bond making ALWAYS releases energy.

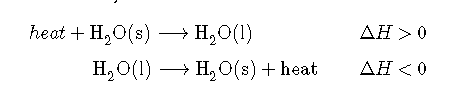

Reversing a reaction or a process changes the sign of ΔH. Ice absorbs heat when it melts (electrostatic interactions are broken), so liquid water must release heat when it freezes (electrostatic interactions are formed):

In both cases, the magnitude of the enthalpy change is the same; only the sign is different.

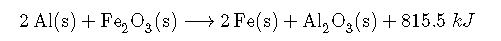

Enthalpy is an extensive property (like mass). The magnitude of ΔH for a reaction is proportional to the amounts of the substances that react. For example, a large fire produces more heat than a single match, even though the chemical reaction—the combustion of wood—is the same in both cases. For this reason, the enthalpy change for a reaction is usually given in kilojoules per mole of a particular reactant or product. Consider Equation, which describes the reaction of aluminum with iron(III) oxide (Fe2O3) at constant pressure. According to the reaction stoichiometry, 2 mol of Fe, 1 mol of Al2O3, and 851.5 kJ of heat are produced for every 2 mol of Al and 1 mol of Fe2O3 consumed:

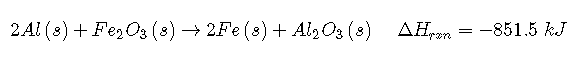

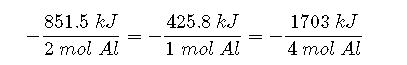

Thus ΔH = −851.5 kJ/mol of Fe2O3. We can also describe ΔH for the reaction as −425.8 kJ/mol of Al: because 2 mol of Al are consumed in the balanced chemical equation, we divide −851.5 kJ by 2. When a value for ΔH, in kilojoules rather than kilojoules per mole, is written after the reaction, as in Equation 7.6.10, it is the value of ΔH corresponding to the reaction of the molar quantities of reactants as given in the balanced chemical equation:

If 4 mol of Al and 2 mol of Fe2O3 react, the change in enthalpy is 2 × (−851.5 kJ) = −1703 kJ. We can summarize the relationship between the amount of each substance and the enthalpy change for this reaction as follows:

Types of Enthalpies of Reactions

One way to report the heat absorbed or released would be to compile a massive set of reference tables that list the enthalpy changes for all possible chemical reactions, which would require an incredible amount of effort. Fortunately, Hess’s law allows us to calculate the enthalpy change for virtually any conceivable chemical reaction using a relatively small set of tabulated data, such as the following:

Enthalpy of combustion (ΔHcomb) The change in enthalpy that occurs during a combustion reaction. Enthalpy changes have been measured for the combustion of virtually any substance that will burn in oxygen; these values are usually reported as the enthalpy of combustion per mole of substance.

Enthalpy of fusion (ΔHfus) The enthalpy change that acompanies the melting (fusion) of 1 mol of a substance. The enthalpy change that accompanies the melting, or fusion, of 1 mol of a substance; these values have been measured for almost all the elements and for most simple compounds.

Enthalpy of vaporization (ΔHvap) The enthalpy change that accompanies the vaporization of 1 mol of a substance. The enthalpy change that accompanies the vaporization of 1 mol of a substance; these values have also been measured for nearly all the elements and for most volatile compounds.

Enthalpy of solution (ΔHsoln) The change in enthalpy that occurs when a specified amount of solute dissolves in a given quantity of solvent. The enthalpy change when a specified amount of solute dissolves in a given quantity of solvent.

| Substance | ΔHvap (kJ/mol) | ΔHfus (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| argon (Ar) | 6.3 | 1.3 |

| methane (CH4) | 9.2 | 0.84 |

| ethanol (CH3CH2OH) | 39.3 | 7.6 |

| benzene (C6H6) | 31.0 | 10.9 |

| water (H2O) | 40.7 | 6.0 |

| mercury (Hg) | 59.0 | 2.29 |

| iron (Fe) | 340 | 14 |

The sign convention is the same for all enthalpy changes: negative if heat is released by the system and positive if heat is absorbed by the system.

Summary

Enthalpy is a state function used to measure the heat transferred from a system to its surroundings or vice versa at constant pressure. Only the change in enthalpy (ΔH) can be measured. A negative ΔH means that heat flows from a system to its surroundings; a positive ΔH means that heat flows into a system from its surroundings. For a chemical reaction, the enthalpy of reaction (ΔHrxn) is the difference in enthalpy between products and reactants; the units of ΔHrxn are kilojoules per mole. Reversing a chemical reaction reverses the sign of ΔHrxn.