Because enthalpy is a state function, the enthalpy change for a reaction depends on only two things:

the masses of the reacting substances and

the physical states of the reactants and products.

It does not depend on the path by which reactants are converted to products. If you climbed a mountain, for example, the altitude change would not depend on whether you climbed the entire way without stopping or you stopped many times to take a break. If you stopped often, the overall change in altitude would be the sum of the changes in altitude for each short stretch climbed. Similarly, when we add two or more balanced chemical equations to obtain a net chemical equation, ΔH for the net reaction is the sum of the ΔH values for the individual reactions. This principle is called Hess’s law, after the Swiss-born Russian chemist Germain Hess (1802–1850), a pioneer in the study of thermochemistry. Hess’s law allows us to calculate ΔH values for reactions that are difficult to carry out directly by adding together the known ΔH values for individual steps that give the overall reaction, even though the overall reaction may not actually occur via those steps.

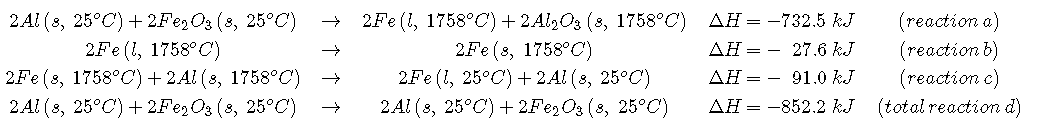

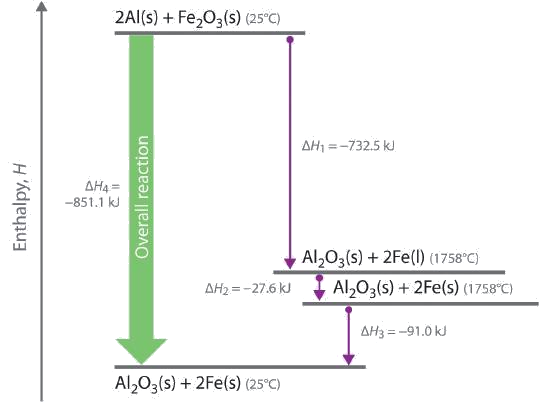

We can illustrate Hess’s law using the thermite reaction. The overall reaction shown in Equation can be viewed as occurring in three distinct steps with known ΔH values. As shown in Figure , the first reaction produces 1 mol of solid aluminum oxide (Al2O3) and 2 mol of liquid iron at its melting point of 1758°C (part (a) in Equation); the enthalpy change for this reaction is −732.5 kJ/mol of Fe2O3. The second reaction is the conversion of 2 mol of liquid iron at 1758°C to 2 mol of solid iron at 1758°C (part (b) in Equation \ref[12.7.1}); the enthalpy change for this reaction is −13.8 kJ/mol of Fe (−27.6 kJ per 2 mol Fe). In the third reaction, 2 mol of solid iron at 1758°C is converted to 2 mol of solid iron at 25°C (part (c) in Equation); the enthalpy change for this reaction is −45.5 kJ/mol of Fe (−91.0 kJ per 2 mol Fe). As you can see in Figure , the overall reaction is given by the longest arrow (shown on the left), which is the sum of the three shorter arrows (shown on the right). Adding parts (a), (b), and (c) in Equation gives the overall reaction, shown in part (d):

By Hess’s law, the enthalpy change for part (d) is the sum of the enthalpy changes for parts (a), (b), and (c). In essence, Hess’s law enables us to calculate the enthalpy change for the sum of a series of reactions without having to draw a diagram like that in Figure .

Comparing parts (a) and (d) in Equation also illustrates an important point: The magnitude of ΔH for a reaction depends on the physical states of the reactants and the products (gas, liquid, solid, or solution). When the product is liquid iron at its melting point (part (a) in Equation), only 732.5 kJ of heat are released to the surroundings compared with 852 kJ when the product is solid iron at 25°C (part (d) in Equation ). The difference, 120 kJ, is the amount of energy that is released when 2 mol of liquid iron solidifies and cools to 25°C. It is important to specify the physical state of all reactants and products when writing a thermochemical equation.

When using Hess’s law to calculate the value of ΔH for a reaction, follow this procedure:

Identify the equation whose value is unknown and write individual reactions with known values that, when added together, will give the desired equation.

Arrange the chemical equations so that the reaction of interest is the sum of the individual reactions.

If a reaction must be reversed, change the sign of for that reaction. Additionally, if a reaction must be multiplied by a factor to obtain the correct number of moles of a substance, multiply its value by that same factor.

Add together the individual reactions and their corresponding values to obtain the reaction of interest and the unknown ΔH.

Enthalpies of Reaction

One way to report the heat absorbed or released would be to compile a massive set of reference tables that list the enthalpy changes for all possible chemical reactions, which would require an incredible amount of effort. Fortunately, Hess’s law allows us to calculate the enthalpy change for virtually any conceivable chemical reaction using a relatively small set of tabulated data, such as the following:

Enthalpy of combustion (ΔHcomb) The change in enthalpy that occurs during a combustion reaction. Enthalpy changes have been measured for the combustion of virtually any substance that will burn in oxygen; these values are usually reported as the enthalpy of combustion per mole of substance.

Enthalpy of fusion (ΔHfus) The enthalpy change that acompanies the melting (fusion) of 1 mol of a substance. The enthalpy change that accompanies the melting, or fusion, of 1 mol of a substance; these values have been measured for almost all the elements and for most simple compounds.

Enthalpy of vaporization (ΔHvap) The enthalpy change that accompanies the vaporization of 1 mol of a substance. The enthalpy change that accompanies the vaporization of 1 mol of a substance; these values have also been measured for nearly all the elements and for most volatile compounds.

Enthalpy of solution (ΔHsoln) The change in enthalpy that occurs when a specified amount of solute dissolves in a given quantity of solvent. The enthalpy change when a specified amount of solute dissolves in a given quantity of solvent.

| Substance | ΔHvap (kJ/mol) | ΔHfus (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| argon (Ar) | 6.3 | 1.3 |

| methane (CH4) | 9.2 | 0.84 |

| ethanol (CH3CH2OH) | 39.3 | 7.6 |

| benzene (C6H6) | 31.0 | 10.9 |

| water (H2O) | 40.7 | 6.0 |

| mercury (Hg) | 59.0 | 2.29 |

| iron (Fe) | 340 | 14 |

The sign convention is the same for all enthalpy changes: negative if heat is released by the system and positive if heat is absorbed by the system.

Summary

Hess's law is that the overall enthalpy change for a series of reactions is the sum of the enthalpy changes for the individual reactions. For a chemical reaction, the enthalpy of reaction (ΔHrxn) is the difference in enthalpy between products and reactants; the units of ΔHrxn are kilojoules per mole. Reversing a chemical reaction reverses the sign of ΔHrxn. The magnitude of ΔHrxn also depends on the physical state of the reactants and the products because processes such as melting solids or vaporizing liquids are also accompanied by enthalpy changes: the enthalpy of fusion (ΔHfus) and the enthalpy of vaporization (ΔHvap), respectively. The overall enthalpy change for a series of reactions is the sum of the enthalpy changes for the individual reactions, which is Hess’s law. The enthalpy of combustion (ΔHcomb) is the enthalpy change that occurs when a substance is burned in excess oxygen.