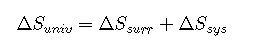

One of the major goals of chemical thermodynamics is to establish criteria for predicting whether a particular reaction or process will occur spontaneously. We have developed one such criterion, the change in entropy of the universe: if for a process or a reaction, then the process will occur spontaneously as written. Conversely, if , a process cannot occur spontaneously; if , the system is at equilibrium. The sign of is a universally applicable and infallible indicator of the spontaneity of a reaction. Unfortunately, using requires that we calculate for both a system and its surroundings. This is not particularly useful for two reasons: we are normally much more interested in the system than in the surroundings, and it is difficult to make quantitative measurements of the surroundings (i.e., the rest of the universe). A criterion of spontaneity that is based solely on the state functions of a system would be much more convenient and is provided by a new state function: the Gibbs free energy.

Gibbs Energy and Spontaneity

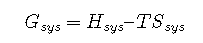

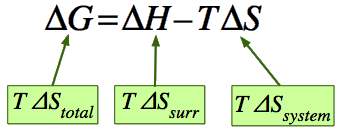

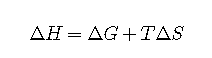

The Gibbs energy (also known as the Gibbs function) is defined as

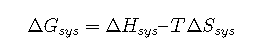

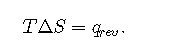

in which refers to the entropy of the system. Since , and are all state functions, so is . Thus for any change in state, we can expand above Equation to

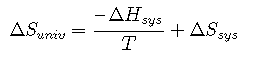

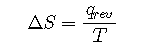

How does this simple equation relate to the entropy change of the universe that we know is the sole criterion for spontaneous change from the second law of thermodynamics? Starting with the definition

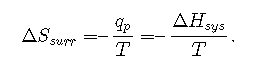

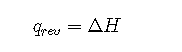

we would first like to get rid of . How can a chemical reaction (a change in the system) affect the entropy of the surroundings? Because most reactions are either exothermic or endothermic, they are accompanied by heat across the system boundary (we are considering constant pressure processes). The enthalpy change of the reaction is the "flow" of heat into the system from the surroundings under constant pressure, so the heat "withdrawn" from the surroundings will be .

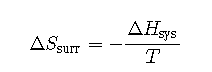

From the thermodynamic definition of entropy, the change of the entropy of the surroundings will be

We can therefore rewrite Equation as

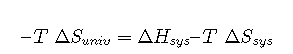

Multiplying through by , we obtain

which expresses the entropy change of the universe in terms of thermodynamic properties of the system exclusively.

If is denoted by , then we have Equation which defines the Gibbs energy change for the process.

The criterion for predicting spontaneity is based on (), the change in , at constant temperature and pressure. Although very few chemical reactions actually occur under conditions of constant temperature and pressure, most systems can be brought back to the initial temperature and pressure without significantly affecting the value of thermodynamic state functions such as . At constant temperature and pressure,

where all thermodynamic quantities are those of the system. Recall that at constant pressure, , whether a process is reversible or irreversible, and

Using these expressions, we can reduce Equation to

Thus is the difference between the heat released during a process (via a reversible or an irreversible path) and the heat released for the same process occurring in a reversible manner. Under the special condition in which a process occurs reversibly, and . As we shall soon see, if is zero, the system is at equilibrium, and there will be no net change.

What about processes for which ? To understand how the sign of for a system determines the direction in which change is spontaneous, we can rewrite the relationship between and , discussed earlier.

with the definition of in terms of

to obtain

Thus the entropy change of the surroundings is related to the enthalpy change of the system. We have stated that for a spontaneous reaction, , so substituting we obtain

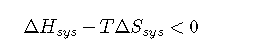

Multiplying both sides of the inequality by reverses the sign of the inequality; rearranging,

which is equal to . We can therefore see that for a spontaneous process, .

The relationship between the entropy change of the surroundings and the heat gained or lost by the system provides the key connection between the thermodynamic properties of the system and the change in entropy of the universe. The relationship shown in Equation allows us to predict spontaneity by focusing exclusively on the thermodynamic properties and temperature of the system. We predict that highly exothermic processes () that increase the disorder of a system (ΔSsys >> 0) would therefore occur spontaneously. An example of such a process is the decomposition of ammonium nitrate fertilizer. Ammonium nitrate was also used to destroy the Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, in 1995. For a system at constant temperature and pressure, we can summarize the following results:

If , the process occurs spontaneously.

If , the system is at equilibrium.

If , the process is not spontaneous as written but occurs spontaneously in the reverse direction.

To further understand how the various components of dictate whether a process occurs spontaneously, we now look at a simple and familiar physical change: the conversion of liquid water to water vapor.

EXAMPLE: VAPORIZING WATER

At Room Temperature (100 °C)

If the conversion of liquid water to water vapor is carried out at 1 atm and the normal boiling point of 100.00 °C (373.15 K), we can calculate from the experimentally measured value of (40.657 kJ/mol). For vaporizing 1 mol of water, , so the process is highly endothermic. From the definition of , we know that for 1 mol of water,

Hence there is an increase in the disorder of the system. At the normal boiling point of water,

The energy required for vaporization offsets the increase in entropy of the system. Thus , and the liquid and vapor are in equilibrium, as is true of any liquid at its boiling point under standard conditions.

Above Room Temperature (110 °C)

Now suppose we were to superheat 1 mol of liquid water to 110°C. The value of for the vaporization of 1 mol of water at 110°C, assuming that and do not change significantly with temperature, becomes

ΔG110∘C=ΔH−TΔS=40,657 J−[(383.15 K)(108.96 J/K)]=−1091 J

Since , the vaporization of water is predicted to occur spontaneously and irreversibly at 110 °C.

Below Room Temperature (90 °C)

We can also calculate for the vaporization of 1 mol of water at a temperature below its normal boiling point—for example, 90°C—making the same assumptions:

ΔG90∘C=ΔH−TΔS=40,657 J−[(363.15 K)(108.96 J/K)]=1088 J

Since , water does not spontaneously convert to water vapor at 90 °C. When using all the digits in the calculator display in carrying out our calculations, ΔG110°C = 1090 J = −ΔG90°C, as we would predict.

Equilibrium Temperature

We can also calculate the temperature at which liquid water is in equilibrium with water vapor. Inserting the values of and into the definition of , setting , and solving for ,

Thus at and , which indicates that liquid water and water vapor are in equilibrium; this temperature is called the normal boiling point of water.

At temperatures greater than 373.15 K, ΔG is negative, and water evaporates spontaneously and irreversibly. Below 373.15 K, is positive, and water does not evaporate spontaneously. Instead, water vapor at a temperature less than 373.15 K and 1 atm will spontaneously and irreversibly condense to liquid water. Figure shows how the and terms vary with temperature for the vaporization of water. When the two lines cross, , and

A similar situation arises in the conversion of liquid egg white to a solid when an egg is boiled. The major component of egg white is a protein called albumin, which is held in a compact, ordered structure by a large number of hydrogen bonds. Breaking them requires an input of energy (ΔH > 0), which converts the albumin to a highly disordered structure in which the molecules aggregate as a disorganized solid (ΔS > 0). At temperatures greater than 373 K, the TΔS term dominates, and ΔG < 0, so the conversion of a raw egg to a hard-boiled egg is an irreversible and spontaneous process above 373 K.

| - (exothermic) | + (products more disordered) | - (favors spontaneity) | - (spontaneous at all T) |

| - (exothermic) | - (products less disordered) | + (opposes spontaneity) | - (spontaneous) at low T + (non-spontaneous) at high T "Enthalpically-driven process" |

| + (endothermic) | + (products more disordered) | - (favors spontaneity) | + (non-spontaneous) at low T - (spontaneous) at high T "Entropically-driven process" |

| + (endothermic) | - (products less disordered) | + (opposes spontaneity) | + (non-spontaneous at all T) |

Enthalpically vs. Entropically Driving Reactions

Some textbooks and teachers say that the free energy, and thus the spontaneity of a reaction, depends on both the enthalpy and entropy changes of a reaction, and they sometimes even refer to reactions as "energy driven" or "entropy driven" depending on whether or the term dominates. This is technically correct, but misleading because it disguises the important fact that , which this equation expresses in an indirect way, is the only criterion of spontaneous change.

Consider the following possible states for two different types of molecules with some attractive force:

There would appear to be greater entropy on the left (state 1) than on the right (state 2). Thus the entropic change for the reaction as written (i.e. going to the right) would be (-) in magnitude, and the energetic contribution to the free energy change would be (+) (i.e. unfavorable) for the reaction as written.

In going to the right, there is an attractive force and the molecules adjacent to each other is a lower energy state (heat energy, q, is liberated). To go to the left, we have to overcome this attractive force (input heat energy) and the left direction is unfavorable with regard to heat energy q. The change in enthalpy is (-) in going to the right (q released), and this enthalpy change is negative (-) in going to the right (and (+) in going to the left). This reaction as written, is therefore, enthalpically favorable and entropically unfavorable. Hence, It is enthalpically driven.

From Table , it would appear that we might be able to get the reaction to go to the right at low temperatures (lower temperature would minimize the energetic contribution of the entropic change). Looking at the same process from an opposite direction:

This reaction as written, is entropically favorable, and enthalpically unfavorable; it is entropically driven. From Table , it would appear that we might be able to get the reaction to go to the right at high temperatures (high temperature would increase the energetic contribution of the entropic change).

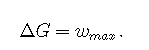

The Relationship between ΔG and Work

In the previous subsection, we learned that the value of allows us to predict the spontaneity of a physical or a chemical change. In addition, the magnitude of for a process provides other important information. The change in Gibbs energy is equal to the maximum amount of work that a system can perform on the surroundings while undergoing a spontaneous change (at constant temperature and pressure):

To see why this is true, let’s look again at the relationships among free energy, enthalpy, and entropy expressed in Equation. We can rearrange this equation as follows:

This equation tells us that when energy is released during an exothermic process (), such as during the combustion of a fuel, some of that energy can be used to do work (), while some is used to increase the entropy of the universe (). Only if the process occurs infinitely slowly in a perfectly reversible manner will the entropy of the universe be unchanged. Because no real system is perfectly reversible, the entropy of the universe increases during all processes that produce energy. As a result, no process that uses stored energy can ever be 100% efficient; that is, will never equal because has a positive value.

One of the major challenges facing engineers is to maximize the efficiency of converting stored energy to useful work or converting one form of energy to another. As indicated in Table , the efficiencies of various energy-converting devices vary widely. For example, an internal combustion engine typically uses only 25%–30% of the energy stored in the hydrocarbon fuel to perform work; the rest of the stored energy is released in an unusable form as heat. In contrast, gas–electric hybrid engines, now used in several models of automobiles, deliver approximately 50% greater fuel efficiency. A large electrical generator is highly efficient (approximately 99%) in converting mechanical to electrical energy, but a typical incandescent light bulb is one of the least efficient devices known (only approximately 5% of the electrical energy is converted to light). In contrast, a mammalian liver cell is a relatively efficient machine and can use fuels such as glucose with an efficiency of 30%–50%.

| Device | Energy Conversion | Approximate Efficiency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| large electrical generator | mechanical → electrical | 99 |

| chemical battery | chemical → electrical | 90 |

| home furnace | chemical → heat | 65 |

| small electric tool | electrical → mechanical | 60 |

| space shuttle engine | chemical → mechanical | 50 |

| mammalian liver cell | chemical → chemical | 30–50 |

| spinach cell | light → chemical | 30 |

| internal combustion engine | chemical → mechanical | 25–30 |

| fluorescent light | electrical → light | 20 |

| solar cell | light → electricity | 10 |

| incandescent light bulb | electricity → light | 5 |

| yeast cell | chemical → chemical | 2–4 |

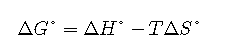

Standard Free-Energy Change

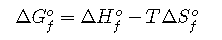

We have seen that there is no way to measure absolute enthalpies, although we can measure changes in enthalpy (ΔH) during a chemical reaction. Because enthalpy is one of the components of Gibbs free energy, we are consequently unable to measure absolute free energies; we can measure only changes in free energy. The standard free-energy change (ΔG°) is the change in free energy when one substance or a set of substances in their standard states is converted to one or more other substances, also in their standard states. The standard free-energy change can be calculated from the definition of free energy, if the standard enthalpy and entropy changes are known, using Equation:

If ΔS° and ΔH° for a reaction have the same sign, then the sign of ΔG° depends on the relative magnitudes of the ΔH° and TΔS° terms. It is important to recognize that a positive value of ΔG° for a reaction does not mean that no products will form if the reactants in their standard states are mixed; it means only that at equilibrium the concentrations of the products will be less than the concentrations of the reactants.

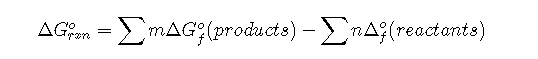

Tabulated values of standard free energies of formation allow chemists to calculate the values of ΔG° for a wide variety of chemical reactions rather than having to measure them in the laboratory. The standard free energy of formation ()of a compound is the change in free energy that occurs when 1 mol of a substance in its standard state is formed from the component elements in their standard states. By definition, the standard free energy of formation of an element in its standard state is zero at 298.15 K. One mole of Cl2 gas at 298.15 K, for example, has . The standard free energy of formation of a compound can be calculated from the standard enthalpy of formation (ΔH∘f) and the standard entropy of formation (ΔS∘f) using the definition of free energy:

Using standard free energies of formation to calculate the standard free energy of a reaction is analogous to calculating standard enthalpy changes from standard enthalpies of formation using the familiar “products minus reactants” rule:

where m and n are the stoichiometric coefficients of each product and reactant in the balanced chemical equation. A very large negative ΔG° indicates a strong tendency for products to form spontaneously from reactants; it does not, however, necessarily indicate that the reaction will occur rapidly. To make this determination, we need to evaluate the kinetics of the reaction.

Calculated values of ΔG° are extremely useful in predicting whether a reaction will occur spontaneously if the reactants and products are mixed under standard conditions. We should note, however, that very few reactions are actually carried out under standard conditions, and calculated values of ΔG° may not tell us whether a given reaction will occur spontaneously under nonstandard conditions. What determines whether a reaction will occur spontaneously is the free-energy change (ΔG) under the actual experimental conditions, which are usually different from ΔG°. If the ΔH and TΔS terms for a reaction have the same sign, for example, then it may be possible to reverse the sign of ΔG by changing the temperature, thereby converting a reaction that is not thermodynamically spontaneous, having Keq < 1, to one that is, having a Keq > 1, or vice versa. Because ΔH and ΔS usually do not vary greatly with temperature in the absence of a phase change, we can use tabulated values of ΔH° and ΔS° to calculate ΔG° at various temperatures, as long as no phase change occurs over the temperature range being considered.

Summary

The change in Gibbs free energy, which is based solely on changes in state functions, is the criterion for predicting the spontaneity of a reaction.

Free-energy change

Standard free-energy change

We can predict whether a reaction will occur spontaneously by combining the entropy, enthalpy, and temperature of a system in a new state function called Gibbs free energy (G). The change in free energy (ΔG) is the difference between the heat released during a process and the heat released for the same process occurring in a reversible manner. If a system is at equilibrium, ΔG = 0. If the process is spontaneous, ΔG < 0. If the process is not spontaneous as written but is spontaneous in the reverse direction, ΔG > 0. At constant temperature and pressure, ΔG is equal to the maximum amount of work a system can perform on its surroundings while undergoing a spontaneous change. The standard free-energy change (ΔG°) is the change in free energy when one substance or a set of substances in their standard states is converted to one or more other substances, also in their standard states. The standard free energy of formation (ΔG∘f), is the change in free energy that occurs when 1 mol of a substance in its standard state is formed from the component elements in their standard states. Tabulated values of standard free energies of formation are used to calculate ΔG° for a reaction.