In an acid–base titration, a buret is used to deliver measured volumes of an acid or a base solution of known concentration (the titrant) to a flask that contains a solution of a base or an acid, respectively, of unknown concentration (the unknown). If the concentration of the titrant is known, then the concentration of the unknown can be determined. The following discussion focuses on the pH changes that occur during an acid–base titration. Plotting the pH of the solution in the flask against the amount of acid or base added produces a titration curve. The shape of the curve provides important information about what is occurring in solution during the titration.

Titrations of Strong Acids and Bases

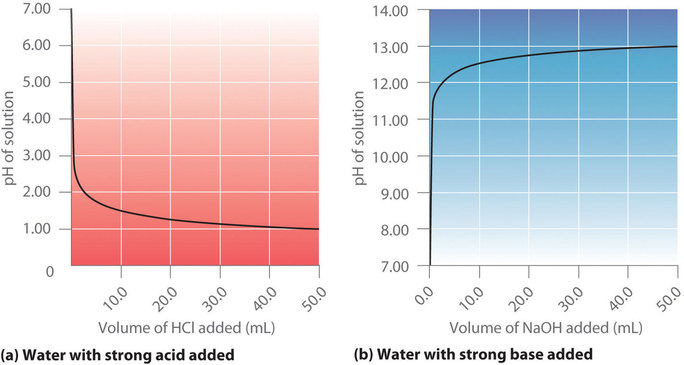

Figure shows a plot of the pH as 0.20 M HCl is gradually added to 50.00 mL of pure water. The pH of the sample in the flask is initially 7.00 (as expected for pure water), but it drops very rapidly as HCl is added. Eventually the pH becomes constant at 0.70—a point well beyond its value of 1.00 with the addition of 50.0 mL of HCl (0.70 is the pH of 0.20 M HCl). In contrast, when 0.20 M is added to 50.00 mL of distilled water, the pH (initially 7.00) climbs very rapidly at first but then more gradually, eventually approaching a limit of 13.30 (the pH of 0.20 M NaOH), again well beyond its value of 13.00 with the addition of 50.0 mL of as shown in Figure . As you can see from these plots, the titration curve for adding a base is the mirror image of the curve for adding an acid.

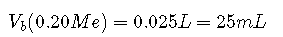

Suppose that we now add 0.20 M to 50.0 mL of a 0.10 M solution of HCl. Because HCl is a strong acid that is completely ionized in water, the initial is 0.10 M, and the initial pH is 1.00. Adding decreases the concentration of H+ because of the neutralization reaction: () (in part (a) in Figure ). Thus the pH of the solution increases gradually. Near the equivalence point, however, the point at which the number of moles of base (or acid) added equals the number of moles of acid (or base) originally present in the solution, the pH increases much more rapidly because most of the H+ ions originally present have been consumed. For the titration of a monoprotic strong acid (HCl) with a monobasic strong base (NaOH), we can calculate the volume of base needed to reach the equivalence point from the following relationship:

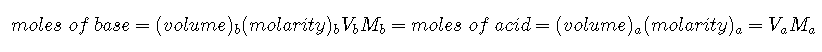

If 0.20 M is added to 50.0 mL of a 0.10 M solution of HCl, we solve for :

At the equivalence point (when 25.0 mL of solution has been added), the neutralization is complete: only a salt remains in solution (NaCl), and the pH of the solution is 7.00. Adding more produces a rapid increase in pH, but eventually the pH levels off at a value of about 13.30, the pH of 0.20 M .

As shown in Figure , the titration of 50.0 mL of a 0.10 M solution of with 0.20 M produces a titration curve that is nearly the mirror image of the titration curve in Figure . The pH is initially 13.00, and it slowly decreases as is added. As the equivalence point is approached, the pH drops rapidly before leveling off at a value of about 0.70, the pH of 0.20 M HCl.

The titration of either a strong acid with a strong base or a strong base with a strong acid produces an S-shaped curve. The curve is somewhat asymmetrical because the steady increase in the volume of the solution during the titration causes the solution to become more dilute. Due to the leveling effect, the shape of the curve for a titration involving a strong acid and a strong base depends on only the concentrations of the acid and base, not their identities.

Titrations of Weak Acids and Bases

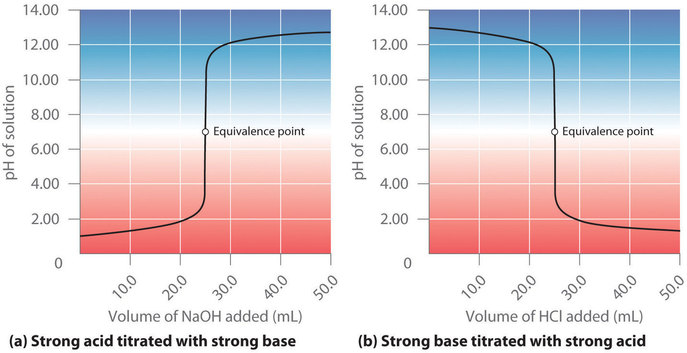

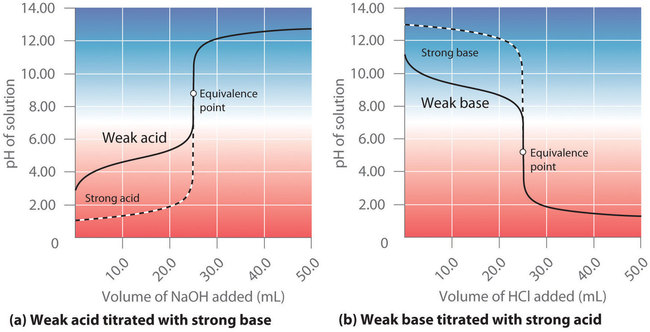

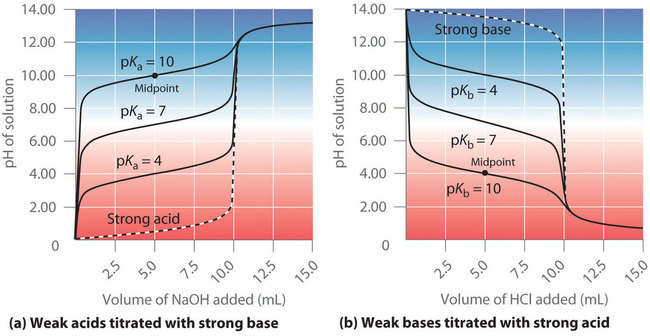

In contrast to strong acids and bases, the shape of the titration curve for a weak acid or a weak base depends dramatically on the identity of the acid or the base and the corresponding or . As we shall see, the pH also changes much more gradually around the equivalence point in the titration of a weak acid or a weak base. As you learned previously, of a solution of a weak acid (HA) is not equal to the concentration of the acid but depends on both its and its concentration. Because only a fraction of a weak acid dissociates, is less than . Thus the pH of a solution of a weak acid is greater than the pH of a solution of a strong acid of the same concentration. Figure shows the titration curve for 50.0 mL of a 0.100 M solution of acetic acid with 0.200 M superimposed on the curve for the titration of 0.100 M HCl shown in part (a) in Figure . Below the equivalence point, the two curves are very different. Before any base is added, the pH of the acetic acid solution is greater than the pH of the HCl solution, and the pH changes more rapidly during the first part of the titration. Note also that the pH of the acetic acid solution at the equivalence point is greater than 7.00. That is, at the equivalence point, the solution is basic. In addition, the change in pH around the equivalence point is only about half as large as for the HCl titration; the magnitude of the pH change at the equivalence point depends on the of the acid being titrated. Above the equivalence point, however, the two curves are identical. Once the acid has been neutralized, the pH of the solution is controlled only by the amount of excess present, regardless of whether the acid is weak or strong.

The titration curve in Figure was created by calculating the starting pH of the acetic acid solution before any is added and then calculating the pH of the solution after adding increasing volumes of .

Calculating the pH of a Solution of a Weak Acid or a Weak Base

As explained discussed, if we know or and the initial concentration of a weak acid or a weak base, we can calculate the pH of a solution of a weak acid or a weak base by setting up a ICE table (i.e, initial concentrations, changes in concentrations, and final concentrations). In this situation, the initial concentration of acetic acid is 0.100 M. If we define as due to the dissociation of the acid, then the table of concentrations for the ionization of 0.100 M acetic acid is as follows:

| ICE | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| initial | 0.100 | 0 | |

| change | −x | +x | +x |

| final | 0.100 − x | x | x |

In this and all subsequent examples, we will ignore and due to the autoionization of water when calculating the final concentration. However, you should use Equation 16.45 and Equation 16.46 to check that this assumption is justified.

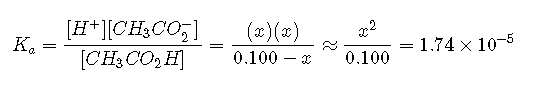

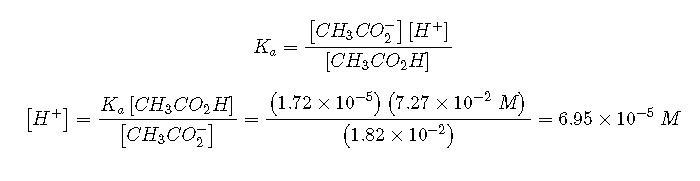

Inserting the expressions for the final concentrations into the equilibrium equation (and using approximations),

Solving this equation gives . Thus the pH of a 0.100 M solution of acetic acid is as follows:

Calculating the pH during the Titration of a Weak Acid or a Weak Base

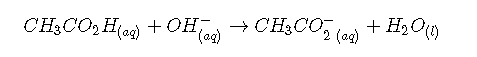

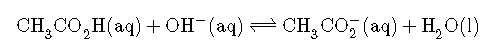

Now consider what happens when we add 5.00 mL of 0.200 M to 50.00 mL of 0.100 M (part (a) in Figure ). Because the neutralization reaction proceeds to completion, all of the ions added will react with the acetic acid to generate acetate ion and water:

All problems of this type must be solved in two steps: a stoichiometric calculation followed by an equilibrium calculation. In the first step, we use the stoichiometry of the neutralization reaction to calculate the amounts of acid and conjugate base present in solution after the neutralization reaction has occurred. In the second step, we use the equilibrium equation to determine of the resulting solution.

Step 1

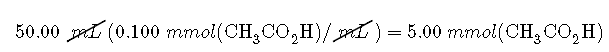

To determine the amount of acid and conjugate base in solution after the neutralization reaction, we calculate the amount of in the original solution and the amount of in the solution that was added. The acetic acid solution contained

The solution contained

5.00 mL=1.00 mmol

Comparing the amounts shows that is in excess. Because reacts with in a 1:1 stoichiometry, the amount of excess is as follows:

5.00 mmol − 1.00 mmol = 4.00 mmol

Each 1 mmol of reacts to produce 1 mmol of acetate ion, so the final amount of is 1.00 mmol.

The stoichiometry of the reaction is summarized in the following table, which shows the numbers of moles of the various species, not their concentrations.

| ICE | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| initial | 5.00 mmol | 1.00 mmol | 0 mmol |

| change | −1.00 mmol | −1.00 mmol | +1.00 mmol |

| final | 4.00 mmol | 0 mmol | 1.00 mmol |

This ICE table gives the initial amount of acetate and the final amount of ions as 0. Because an aqueous solution of acetic acid always contains at least a small amount of acetate ion in equilibrium with acetic acid, however, the initial acetate concentration is not actually 0. The value can be ignored in this calculation because the amount of in equilibrium is insignificant compared to the amount of added. Moreover, due to the autoionization of water, no aqueous solution can contain 0 mmol of , but the amount of due to the autoionization of water is insignificant compared to the amount of added. We use the initial amounts of the reactants to determine the stoichiometry of the reaction and defer a consideration of the equilibrium until the second half of the problem.

Step 2

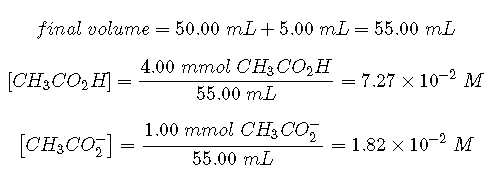

To calculate at equilibrium following the addition of , we must first calculate [] and using the number of millimoles of each and the total volume of the solution at this point in the titration:

Knowing the concentrations of acetic acid and acetate ion at equilibrium and for acetic acid (), we can calculate at equilibrium:

Calculating gives

Comparing the titration curves for HCl and acetic acid in Figure , we see that adding the same amount (5.00 mL) of 0.200 M to 50 mL of a 0.100 M solution of both acids causes a much smaller pH change for HCl (from 1.00 to 1.14) than for acetic acid (2.88 to 4.16). This is consistent with the qualitative description of the shapes of the titration curves at the beginning of this section.

As shown in part (b) in Figure , the titration curve for NH3, a weak base, is the reverse of the titration curve for acetic acid. In particular, the pH at the equivalence point in the titration of a weak base is less than 7.00 because the titration produces an acid.

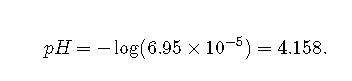

The identity of the weak acid or weak base being titrated strongly affects the shape of the titration curve. Figure illustrates the shape of titration curves as a function of the or the . As the acid or the base being titrated becomes weaker (its or becomes larger), the pH change around the equivalence point decreases significantly. With very dilute solutions, the curve becomes so shallow that it can no longer be used to determine the equivalence point.

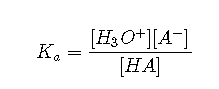

One point in the titration of a weak acid or a weak base is particularly important: the midpoint of a titration is defined as the point at which exactly enough acid (or base) has been added to neutralize one-half of the acid (or the base) originally present and occurs halfway to the equivalence point. The midpoint is indicated in Figures and for the two shallowest curves. By definition, at the midpoint of the titration of an acid, [HA] = [A−]. Recall that the ionization constant for a weak acid is as follows:

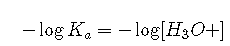

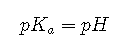

If , this reduces to . Taking the negative logarithm of both sides,

From the definitions of and pH, we see that this is identical to

Thus the pH at the midpoint of the titration of a weak acid is equal to the of the weak acid, as indicated in part (a) in Figure for the weakest acid where we see that the midpoint for = 10 occurs at pH = 10. Titration methods can therefore be used to determine both the concentration and the (or the ) of a weak acid (or a weak base).

Titrations of Polyprotic Acids or Bases

When a strong base is added to a solution of a polyprotic acid, the neutralization reaction occurs in stages. The most acidic group is titrated first, followed by the next most acidic, and so forth. If the units, then the overall titration curve shows well-resolved “steps” corresponding to the titration of each proton. A titration of the triprotic acid with is illustrated in Figure and shows two well-defined steps: the first midpoint corresponds to 1, and the second midpoint corresponds to 2. Because HPO42− is such a weak acid, 3 has such a high value that the third step cannot be resolved using 0.100 M as the titrant.

The titration curve for the reaction of a polyprotic base with a strong acid is the mirror image of the curve shown in Figure . The initial pH is high, but as acid is added, the pH decreases in steps if the successive values are well separated.

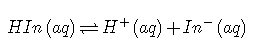

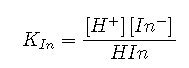

In practice, most acid–base titrations are not monitored by recording the pH as a function of the amount of the strong acid or base solution used as the titrant. Instead, an acid–base indicator is often used that, if carefully selected, undergoes a dramatic color change at the pH corresponding to the equivalence point of the titration. Indicators are weak acids or bases that exhibit intense colors that vary with pH. The conjugate acid and conjugate base of a good indicator have very different colors so that they can be distinguished easily. Some indicators are colorless in the conjugate acid form but intensely colored when deprotonated (phenolphthalein, for example), which makes them particularly useful. We can describe the chemistry of indicators by the following general equation: The ionization constant for the deprotonation of indicator is as follows: The pKin (its pKa) determines the pH at which the indicator changes color. Many different substances can be used as indicators, depending on the particular reaction to be monitored. For example, red cabbage juice contains a mixture of colored substances that change from deep red at low pH to light blue at intermediate pH to yellow at high pH (Figure ). In all cases, though, a good indicator must have the following properties: The color change must be easily detected. The color change must be rapid. The indicator molecule must not react with the substance being titrated. To minimize errors, the indicator should have a pKin that is within one pH unit of the expected pH at the equivalence point of the titration. Red cabbage juice contains a mixture of substances whose color depends on the pH. Each test tube contains a solution of red cabbage juice in water, but the pH of the solutions varies from pH = 2.0 (far left) to pH = 11.0 (far right). At pH = 7.0, the solution is blue. Synthetic indicators have been developed that meet these criteria and cover virtually the entire pH range. Figure shows the approximate pH range over which some common indicators change color and their change in color. In addition, some indicators (such as thymol blue) are polyprotic acids or bases, which change color twice at widely separated pH values. It is important to be aware that an indicator does not change color abruptly at a particular pH value; instead, it actually undergoes a pH titration just like any other acid or base. As the concentration of HIn decreases and the concentration of In− increases, the color of the solution slowly changes from the characteristic color of HIn to that of In−. As we will see later, the [In−]/[HIn] ratio changes from 0.1 at a pH one unit below pKin to 10 at a pH one unit above pKin. Thus most indicators change color over a pH range of about two pH units. We have stated that a good indicator should have a pKin value that is close to the expected pH at the equivalence point. For a strong acid–strong base titration, the choice of the indicator is not especially critical due to the very large change in pH that occurs around the equivalence point. In contrast, using the wrong indicator for a titration of a weak acid or a weak base can result in relatively large errors, as illustrated in Figure . This figure shows plots of pH versus volume of base added for the titration of 50.0 mL of a 0.100 M solution of a strong acid (HCl) and a weak acid (acetic acid) with 0.100 M . The pH ranges over which two common indicators (methyl red, , and phenolphthalein, ) change color are also shown. The horizontal bars indicate the pH ranges over which both indicators change color cross the HCl titration curve, where it is almost vertical. Hence both indicators change color when essentially the same volume of has been added (about 50 mL), which corresponds to the equivalence point. In contrast, the titration of acetic acid will give very different results depending on whether methyl red or phenolphthalein is used as the indicator. Although the pH range over which phenolphthalein changes color is slightly greater than the pH at the equivalence point of the strong acid titration, the error will be negligible due to the slope of this portion of the titration curve. Just as with the HCl titration, the phenolphthalein indicator will turn pink when about 50 mL of has been added to the acetic acid solution. In contrast, methyl red begins to change from red to yellow around pH 5, which is near the midpoint of the acetic acid titration, not the equivalence point. Adding only about 25–30 mL of will therefore cause the methyl red indicator to change color, resulting in a huge error. The graph shows the results obtained using two indicators (methyl red and phenolphthalein) for the titration of 0.100 M solutions of a strong acid (HCl) and a weak acid (acetic acid) with 0.100 M . Due to the steepness of the titration curve of a strong acid around the equivalence point, either indicator will rapidly change color at the equivalence point for the titration of the strong acid. In contrast, the pKin for methyl red (5.0) is very close to the of acetic acid (4.76); the midpoint of the color change for methyl red occurs near the midpoint of the titration, rather than at the equivalence point. In general, for titrations of strong acids with strong bases (and vice versa), any indicator with a pKin between about 4.0 and 10.0 will do. For the titration of a weak acid, however, the pH at the equivalence point is greater than 7.0, so an indicator such as phenolphthalein or thymol blue, with pKin > 7.0, should be used. Conversely, for the titration of a weak base, where the pH at the equivalence point is less than 7.0, an indicator such as methyl red or bromocresol blue, with pKin < 7.0, should be used. The existence of many different indicators with different colors and pKin values also provides a convenient way to estimate the pH of a solution without using an expensive electronic pH meter and a fragile pH electrode. Paper or plastic strips impregnated with combinations of indicators are used as “pH paper,” which allows you to estimate the pH of a solution by simply dipping a piece of pH paper into it and comparing the resulting color with the standards printed on the container (Figure ). Plots of acid–base titrations generate titration curves that can be used to calculate the pH, the pOH, the , and the of the system. The shape of a titration curve, a plot of pH versus the amount of acid or base added, provides important information about what is occurring in solution during a titration. The shapes of titration curves for weak acids and bases depend dramatically on the identity of the compound. The equivalence point of an acid–base titration is the point at which exactly enough acid or base has been added to react completely with the other component. The equivalence point in the titration of a strong acid or a strong base occurs at pH 7.0. In titrations of weak acids or weak bases, however, the pH at the equivalence point is greater or less than 7.0, respectively. The pH tends to change more slowly before the equivalence point is reached in titrations of weak acids and weak bases than in titrations of strong acids and strong bases. The pH at the midpoint, the point halfway on the titration curve to the equivalence point, is equal to the of the weak acid or the of the weak base. Thus titration methods can be used to determine both the concentration and the (or the ) of a weak acid (or a weak base). Acid–base indicators are compounds that change color at a particular pH. They are typically weak acids or bases whose changes in color correspond to deprotonation or protonation of the indicator itself.Indicators

Summary and Takeaway