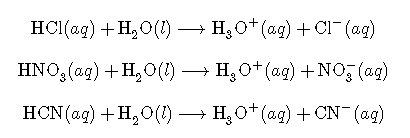

We can classify acids by the number of protons per molecule that they can give up in a reaction. Acids such as , , and that contain one ionizable hydrogen atom in each molecule are called monoprotic acids. Their reactions with water are:

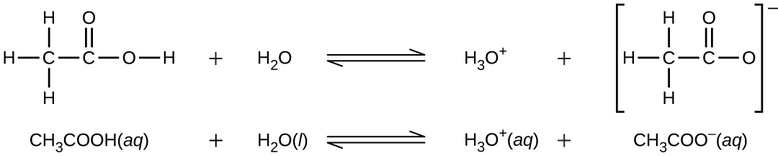

Even though it contains four hydrogen atoms, acetic acid, , is also monoprotic because only the hydrogen atom from the carboxyl group () reacts with bases:

Similarly, monoprotic bases are bases that will accept a single proton.

Diprotic Acids

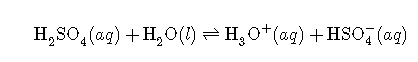

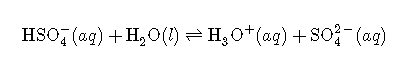

Diprotic acids contain two ionizable hydrogen atoms per molecule; ionization of such acids occurs in two steps. The first ionization always takes place to a greater extent than the second ionization. For example, sulfuric acid, a strong acid, ionizes as follows:

The first ionization is

with

The second ionization is

with .

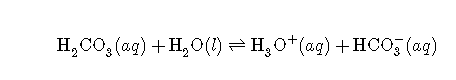

This stepwise ionization process occurs for all polyprotic acids. When we make a solution of a weak diprotic acid, we get a solution that contains a mixture of acids. Carbonic acid, , is an example of a weak diprotic acid. The first ionization of carbonic acid yields hydronium ions and bicarbonate ions in small amounts.

First Ionization

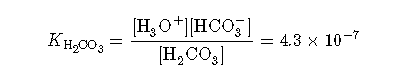

with

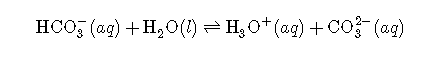

The bicarbonate ion can also act as an acid. It ionizes and forms hydronium ions and carbonate ions in even smaller quantities.

Second Ionization

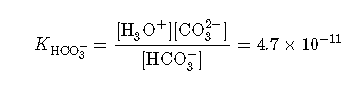

with

is larger than by a factor of 104, so H2CO3 is the dominant producer of hydronium ion in the solution. This means that little of the formed by the ionization of H2CO3 ionizes to give hydronium ions (and carbonate ions), and the concentrations of H3O+ and are practically equal in a pure aqueous solution of H2CO3.

If the first ionization constant of a weak diprotic acid is larger than the second by a factor of at least 20, it is appropriate to treat the first ionization separately and calculate concentrations resulting from it before calculating concentrations of species resulting from subsequent ionization. This can simplify our work considerably because we can determine the concentration of H3O+ and the conjugate base from the first ionization, then determine the concentration of the conjugate base of the second ionization in a solution with concentrations determined by the first ionization.

Triprotic Acids

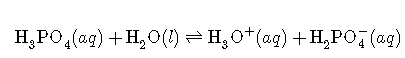

A triprotic acid is an acid that has three dissociable protons that undergo stepwise ionization: Phosphoric acid is a typical example:

The first ionization is

with .

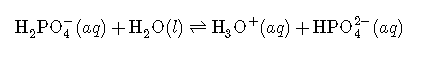

The second ionization is

with .

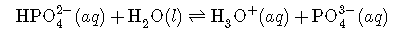

The third ionization is

with .

As with the diprotic acids, the differences in the ionization constants of these reactions tell us that in each successive step the degree of ionization is significantly weaker. This is a general characteristic of polyprotic acids and successive ionization constants often differ by a factor of about 105 to 106. This set of three dissociation reactions may appear to make calculations of equilibrium concentrations in a solution of H3PO4 complicated. However, because the successive ionization constants differ by a factor of 105 to 106, the calculations can be broken down into a series of parts similar to those for diprotic acids.

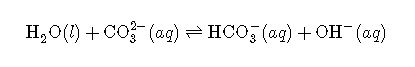

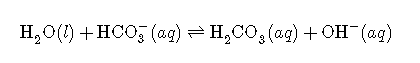

Polyprotic bases can accept more than one hydrogen ion in solution. The carbonate ion is an example of a diprotic base, since it can accept up to two protons. Solutions of alkali metal carbonates are quite alkaline, due to the reactions:

and

Summary

An acid that contains more than one ionizable proton is a polyprotic acid. The protons of these acids ionize in steps. The differences in the acid ionization constants for the successive ionizations of the protons in a polyprotic acid usually vary by roughly five orders of magnitude. As long as the difference between the successive values of Ka of the acid is greater than about a factor of 20, it is appropriate to break down the calculations of the concentrations of the ions in solution into a series of steps.