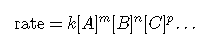

As described in the previous module, the rate of a reaction is affected by the concentrations of reactants. Rate laws or rate equations are mathematical expressions that describe the relationship between the rate of a chemical reaction and the concentration of its reactants. In general, a rate law (or differential rate law, as it is sometimes called) takes this form:

in which [A], [B], and [C] represent the molar concentrations of reactants, and k is the rate constant, which is specific for a particular reaction at a particular temperature. The exponents m, n, and p are usually positive integers (although it is possible for them to be fractions or negative numbers). The rate constant kand the exponents m, n, and p must be determined experimentally by observing how the rate of a reaction changes as the concentrations of the reactants are changed. The rate constant k is independent of the concentration of A, B, or C, but it does vary with temperature and surface area.

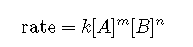

The exponents in a rate law describe the effects of the reactant concentrations on the reaction rate and define the reaction order. Consider a reaction for which the rate law is:

If the exponent m is 1, the reaction is first order with respect to A. If m is 2, the reaction is second order with respect to A. If n is 1, the reaction is first order in B. If n is 2, the reaction is second order in B. If m or n is zero, the reaction is zero order in A or B, respectively, and the rate of the reaction is not affected by the concentration of that reactant. The overall reaction order is the sum of the orders with respect to each reactant. If m = 1 and n = 1, the overall order of the reaction is second order (m + n = 1 + 1 = 2).

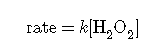

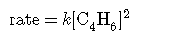

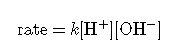

The rate law:

rate law:

describes a reaction that is second order in C4H6 and second order overall. The rate law:

describes a reaction that is first order in H+, first order in OH−, and second order overall.

It is sometimes helpful to use a more explicit algebraic method, often referred to as the method of initial rates, to determine the orders in rate laws. To use this method, we select two sets of rate data that differ in the concentration of only one reactant and set up a ratio of the two rates and the two rate laws. After canceling terms that are equal, we are left with an equation that contains only one unknown, the coefficient of the concentration that varies. We then solve this equation for the coefficient.

Reaction Order and Rate Constant Units

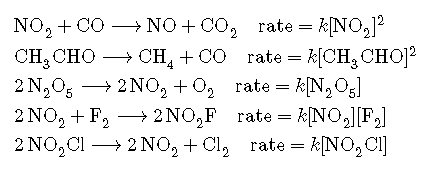

In some of our examples, the reaction orders in the rate law happen to be the same as the coefficients in the chemical equation for the reaction. This is merely a coincidence and very often not the case. Rate laws may exhibit fractional orders for some reactants, and negative reaction orders are sometimes observed when an increase in the concentration of one reactant causes a decrease in reaction rate. A few examples illustrating these points are provided:

It is important to note that rate laws are determined by experiment only and are not reliably predicted by reaction stoichiometry.

Reaction orders also play a role in determining the units for the rate constant k. In a second-order reaction, we found the units for k to be , whereas in a third order reaction, we found the units for k to be mol−2 L2/s. More generally speaking, the units for the rate constant for a reaction of order are . Table summarizes the rate constant units for common reaction orders.

| Reaction Order | Units of k |

|---|---|

| zero | mol/L/s |

| first | s−1 |

| second | L/mol/s |

| third | mol−2 L2 s−1 |

Note that the units in the table can also be expressed in terms of molarity (M) instead of mol/L. Also, units of time other than the second (such as minutes, hours, days) may be used, depending on the situation.

Summary

Rate laws provide a mathematical description of how changes in the amount of a substance affect the rate of a chemical reaction. Rate laws are determined experimentally and cannot be predicted by reaction stoichiometry. The order of reaction describes how much a change in the amount of each substance affects the overall rate, and the overall order of a reaction is the sum of the orders for each substance present in the reaction. Reaction orders are typically first order, second order, or zero order, but fractional and even negative orders are possible.