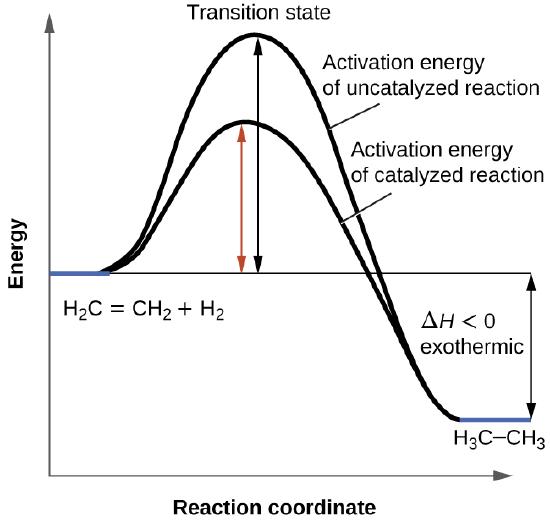

We have seen that the rate of many reactions can be accelerated by catalysts. A catalyst speeds up the rate of a reaction by lowering the activation energy; in addition, the catalyst is regenerated in the process. Several reactions that are thermodynamically favorable in the absence of a catalyst only occur at a reasonable rate when a catalyst is present. One such reaction is catalytic hydrogenation, the process by which hydrogen is added across an alkene C=C bond to afford the saturated alkane product. A comparison of the reaction coordinate diagrams (also known as energy diagrams) for catalyzed and uncatalyzed alkene hydrogenation is shown in Figure .

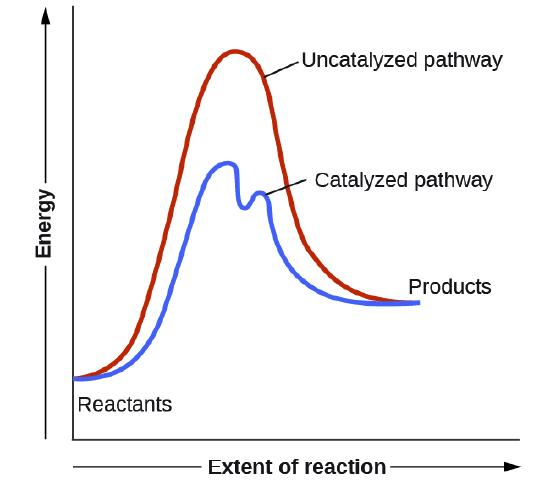

Catalysts function by providing an alternate reaction mechanism that has a lower activation energy than would be found in the absence of the catalyst. In some cases, the catalyzed mechanism may include additional steps, as depicted in the reaction diagrams shown in Figure This lower activation energy results in an increase in rate as described by the Arrhenius equation. Note that a catalyst decreases the activation energy for both the forward and the reverse reactions and hence accelerates both the forward and the reverse reactions. Consequently, the presence of a catalyst will permit a system to reach equilibrium more quickly, but it has no effect on the position of the equilibrium as reflected in the value of its equilibrium constant (see the later chapter on chemical equilibrium).

Homogeneous Catalysts

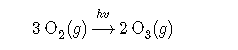

A homogeneous catalyst is present in the same phase as the reactants. It interacts with a reactant to form an intermediate substance, which then decomposes or reacts with another reactant in one or more steps to regenerate the original catalyst and form product. As an important illustration of homogeneous catalysis, consider the earth’s ozone layer. Ozone in the upper atmosphere, which protects the earth from ultraviolet radiation, is formed when oxygen molecules absorb ultraviolet light and undergo the reaction:

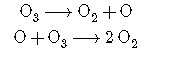

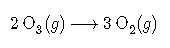

Ozone is a relatively unstable molecule that decomposes to yield diatomic oxygen by the reverse of this equation. This decomposition reaction is consistent with the following mechanism:

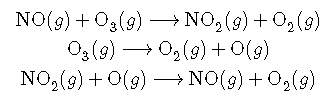

The presence of nitric oxide, NO, influences the rate of decomposition of ozone. Nitric oxide acts as a catalyst in the following mechanism:

The overall chemical change for the catalyzed mechanism is the same as:

The nitric oxide reacts and is regenerated in these reactions. It is not permanently used up; thus, it acts as a catalyst. The rate of decomposition of ozone is greater in the presence of nitric oxide because of the catalytic activity of NO. Certain compounds that contain chlorine also catalyze the decomposition of ozone.

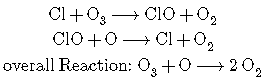

Chlorine radicals break down ozone and are regenerated by the following catalytic cycle: A single monatomic chlorine can break down thousands of ozone molecules. Luckily, the majority of atmospheric chlorine exists as the catalytically inactive forms Cl2 and ClONO2.

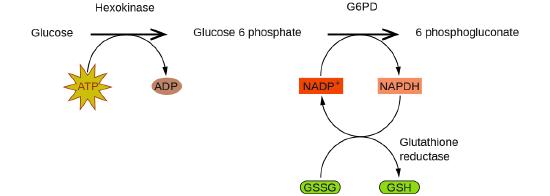

Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase Deficiency

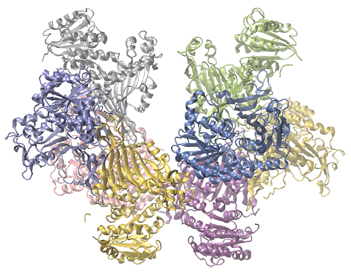

Enzymes in the human body act as catalysts for important chemical reactions in cellular metabolism. As such, a deficiency of a particular enzyme can translate to a life-threatening disease. G6PD (glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase) deficiency, a genetic condition that results in a shortage of the enzyme glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, is the most common enzyme deficiency in humans. This enzyme, shown in Figure , is the rate-limiting enzyme for the metabolic pathway that supplies NADPH to cells (FIgure ).

A disruption in this pathway can lead to reduced glutathione in red blood cells; once all glutathione is consumed, enzymes and other proteins such as hemoglobin are susceptible to damage. For example, hemoglobin can be metabolized to bilirubin, which leads to jaundice, a condition that can become severe. People who suffer from G6PD deficiency must avoid certain foods and medicines containing chemicals that can trigger damage their glutathione-deficient red blood cells.

Heterogeneous Catalysts

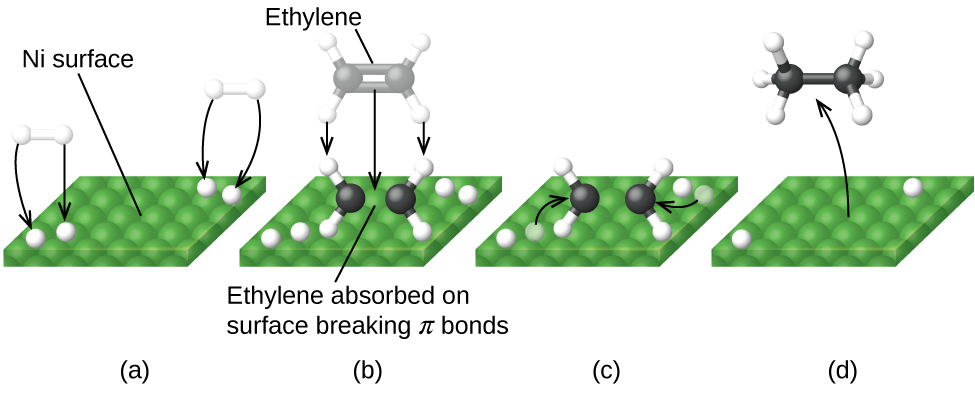

A heterogeneous catalyst is a catalyst that is present in a different phase (usually a solid) than the reactants. Such catalysts generally function by furnishing an active surface upon which a reaction can occur. Gas and liquid phase reactions catalyzed by heterogeneous catalysts occur on the surface of the catalyst rather than within the gas or liquid phase.

Heterogeneous catalysis has at least four steps:

Adsorption of the reactant onto the surface of the catalyst

Activation of the adsorbed reactant

Reaction of the adsorbed reactant

Diffusion of the product from the surface into the gas or liquid phase (desorption).

Any one of these steps may be slow and thus may serve as the rate determining step. In general, however, in the presence of the catalyst, the overall rate of the reaction is faster than it would be if the reactants were in the gas or liquid phase.

Figure illustrates the steps that chemists believe to occur in the reaction of compounds containing a carbon–carbon double bond with hydrogen on a nickel catalyst. Nickel is the catalyst used in the hydrogenation of polyunsaturated fats and oils (which contain several carbon–carbon double bonds) to produce saturated fats and oils (which contain only carbon–carbon single bonds).

Other significant industrial processes that involve the use of heterogeneous catalysts include the preparation of sulfuric acid, the preparation of ammonia, the oxidation of ammonia to nitric acid, and the synthesis of methanol, CH3OH. Heterogeneous catalysts are also used in the catalytic converters found on most gasoline-powered automobiles (Figure ).

In order to be as efficient as possible, most catalytic converters are preheated by an electric heater. This ensures that the metals in the catalyst are fully active even before the automobile exhaust is hot enough to maintain appropriate reaction temperatures.Enzyme Structure and Function

The study of enzymes is an important interconnection between biology and chemistry. Enzymes are usually proteins (polypeptides) that help to control the rate of chemical reactions between biologically important compounds, particularly those that are involved in cellular metabolism. Different classes of enzymes perform a variety of functions, as shown in Table .

| Class | Function |

|---|---|

| oxidoreductases | redox reactions |

| transferases | transfer of functional groups |

| hydrolases | hydrolysis reactions |

| lyases | group elimination to form double bonds |

| isomerases | isomerization |

| ligases | bond formation with ATP hydrolysis |

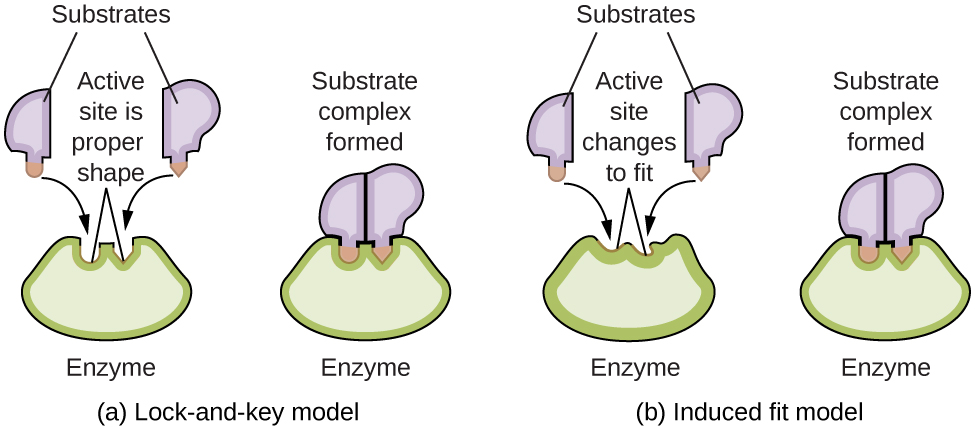

Enzyme molecules possess an active site, a part of the molecule with a shape that allows it to bond to a specific substrate (a reactant molecule), forming an enzyme-substrate complex as a reaction intermediate. There are two models that attempt to explain how this active site works. The most simplistic model is referred to as the lock-and-key hypothesis, which suggests that the molecular shapes of the active site and substrate are complementary, fitting together like a key in a lock. The induced fit hypothesis, on the other hand, suggests that the enzyme molecule is flexible and changes shape to accommodate a bond with the substrate. This is not to suggest that an enzyme’s active site is completely malleable, however. Both the lock-and-key model and the induced fit model account for the fact that enzymes can only bind with specific substrates, since in general a particular enzyme only catalyzes a particular reaction (Figure ).

Summary

Catalysts affect the rate of a chemical reaction by altering its mechanism to provide a lower activation energy. Catalysts can be homogenous (in the same phase as the reactants) or heterogeneous (a different phase than the reactants).