第一节 茎的生理功能与基本形态.

茎由胚芽发育而成,是联系根和叶,输送水、无机盐和有机养料的轴状结构。除少数植物的茎生于地下外,多数茎生长在地上,茎的顶端能无限地向上生长,与叶形成庞大的枝系。乔木和滕本植物的茎可长达几十米至百米,而浦公英等的茎短缩为莲座状。

一、茎的生理功能

1.支持作用

茎是植物地上部分的主轴,对其上着生的叶、芽、花和果实起支持作用。

2.输导作用

根从土壤中吸收的水分、矿物质及养料需要通过茎向上输送至叶、花和果实中,叶片制造的同化产物也需要通过茎输送至植物体的其他部位。

3.蒸腾作用

植物的幼茎上具有气孔,老茎上具有皮孔,可以使水分散失,即蒸腾作用。

4.光合作用

草本植物及一些木本植物的幼茎呈绿色,内含叶绿体,可以进行光合作用。

5.储藏作用

甘蔗的茎含有糖等营养物质,具有储藏功能。

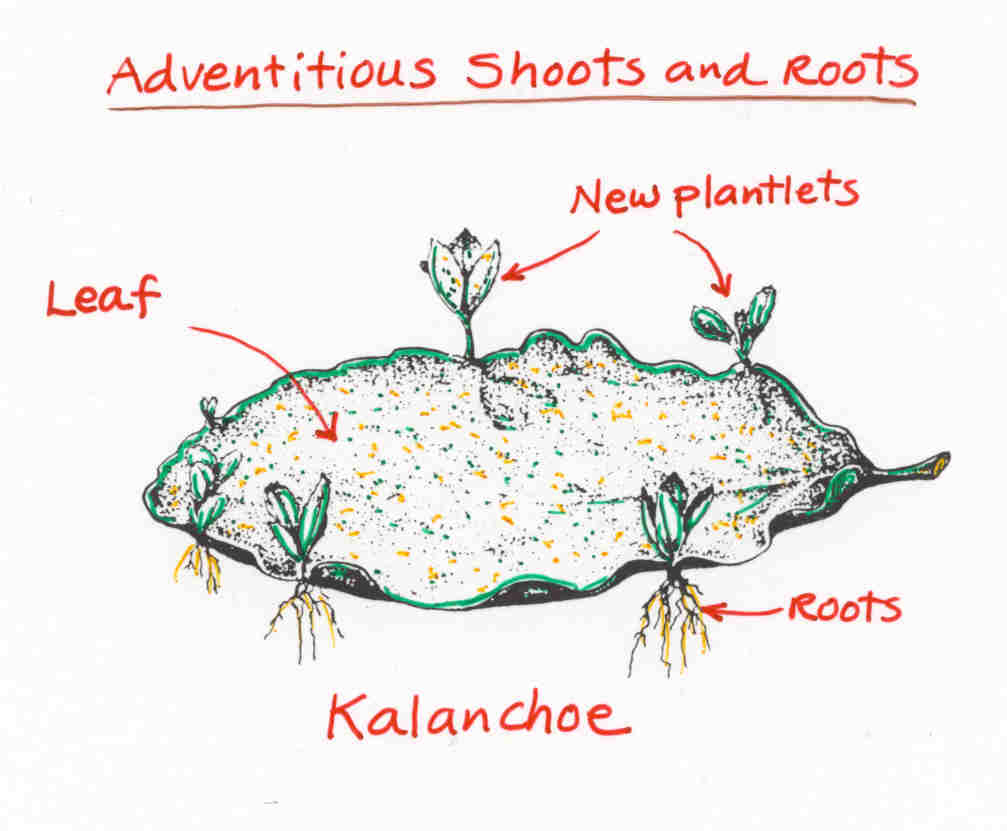

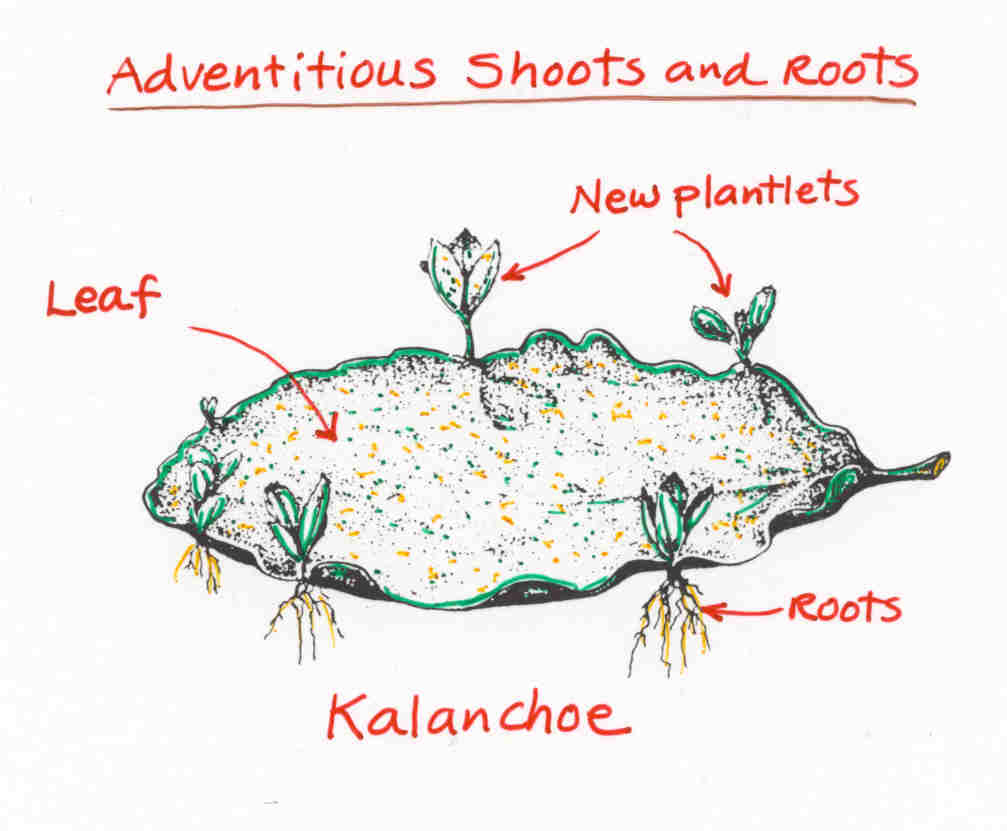

6.繁殖作用

柳树等的枝条可以生出不定根,因此茎也具有繁殖功能。另外,有些植物茎的分枝变为刺,如山植、皂荚的茎刺,具有保护作用; 南瓜、葡萄等植物的一部分枝变为卷须,具攀缘作用; 有的植物(地锦等)的茎含有药用成分,可入药,具有药用价值。

二、 茎的基本形态

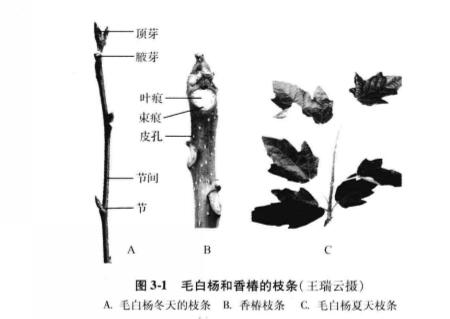

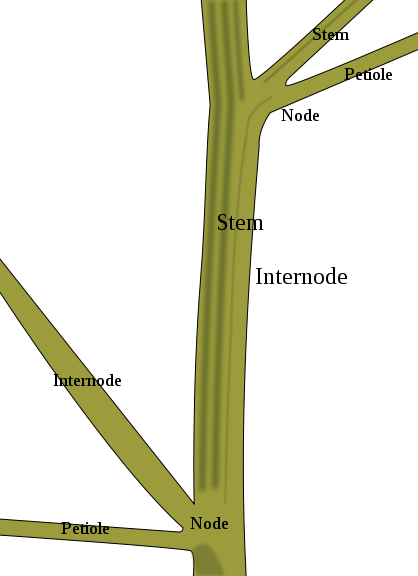

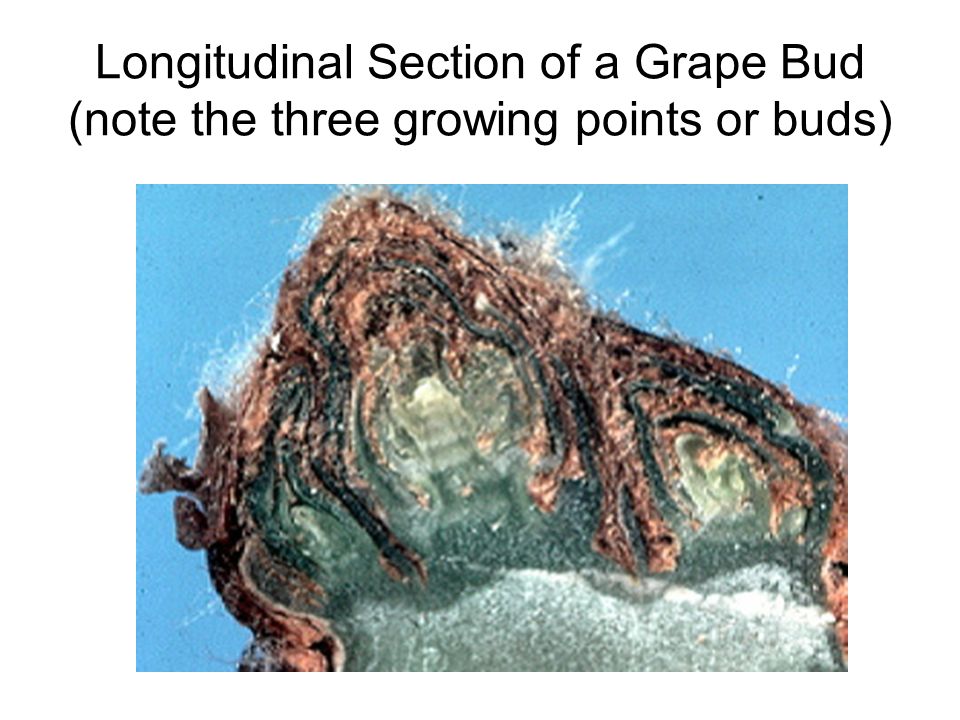

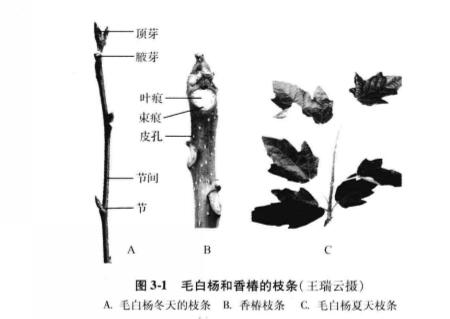

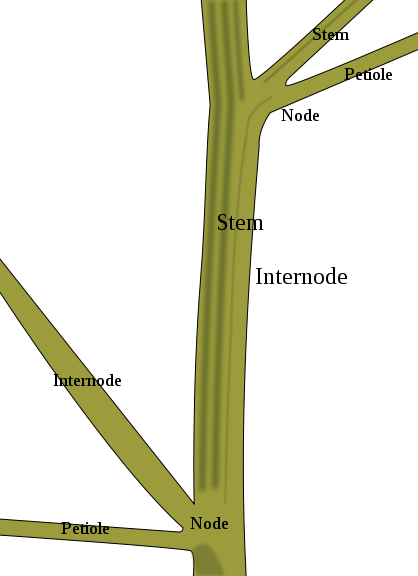

多数植物的茎呈圆柱形,少数呈三角形( 如莎草)、方柱形( 如蚕豆、薄荷、迎春)。茎上着生叶的部位,称为节。两个节之间的部分,称为节间(图3-1)。着生叶和芽的茎,称为枝(或枝条)。

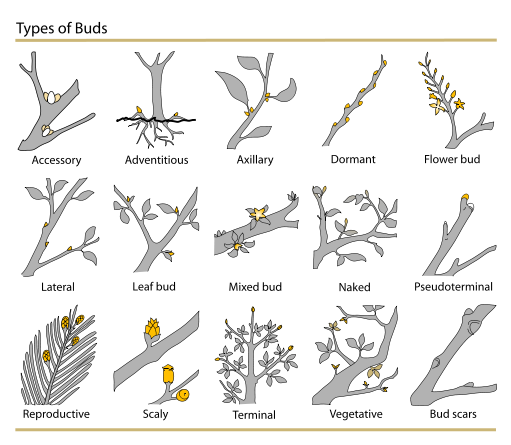

axillary 腋生的

spur:支线

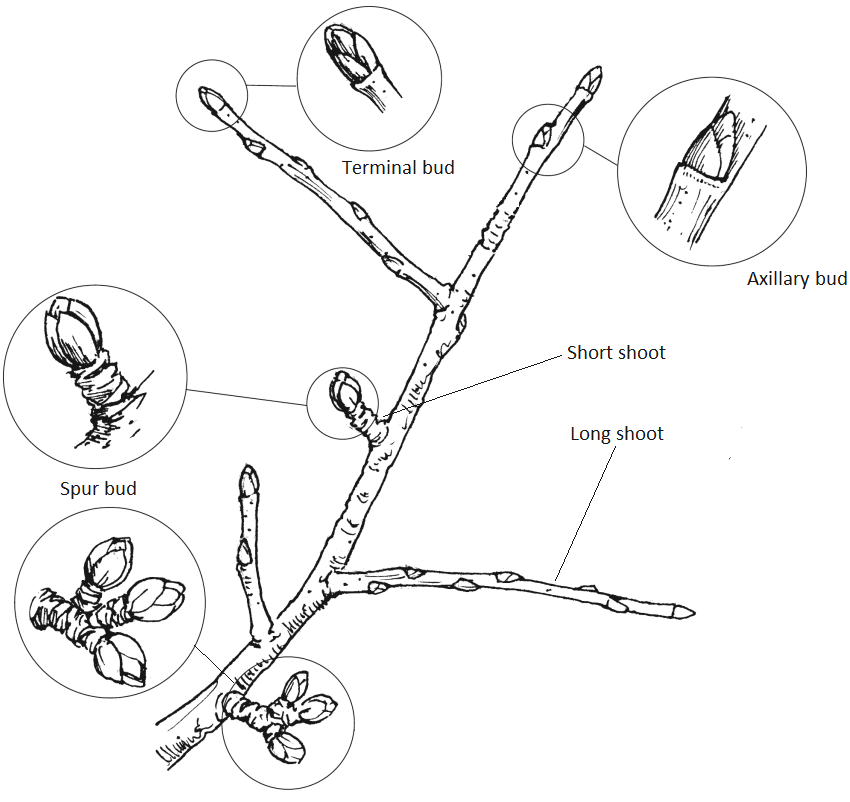

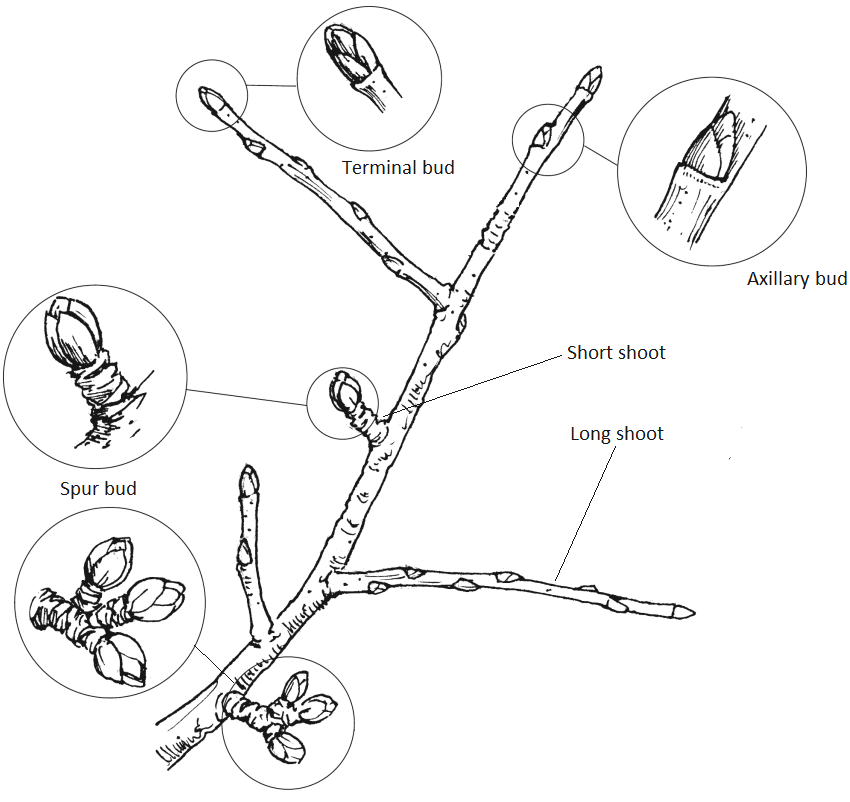

植物的种类不同,节间的长度也不同。在木本植物中,节间显著伸长的枝条称为长枝; 节间短缩,节间密集以致难于分辨的枝条称为短枝。短枝上的叶常呈簇生状态,如雪松; 梨和苹果等果树的花多着生在短枝上; 有些草本植物的节间短缩,叶排列成基生的莲座状,如车前等。

禾本科植物(如玉米,甘蔗等)和蓼科植物(如山荞麦、水夢等)的茎,节部膨大,节明显。少数植物(如莲)的根状茎(藕) 上,节间膨大,节部缩小。

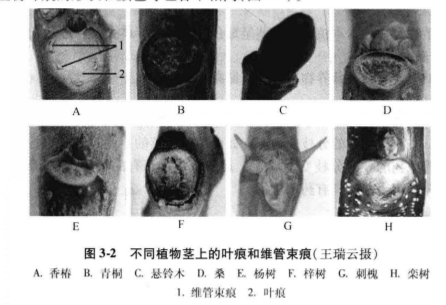

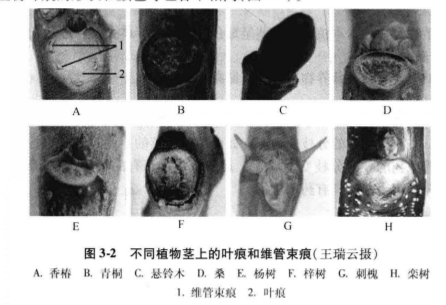

多年生落叶乔木和灌木的冬枝,除了节、节间和芽以外,还可以看到叶痕(leaf scar)(植物落叶后,在茎上:留下的叶柄痕迹)和维管束痕(bundle scar)(叶痕内的点线状突起,是叶柄与茎的维管束断离后留下的痕迹,也被称为“叶迹”)。

有的植物茎上,还可以看到顶芽的芽鳞脱落后留下的痕迹( 芽鳞痕),其形状和数目因植物而异。顶芽每年春季展开一次。有的茎上,还可以看到皮孔(图3-1),这是木质茎内外交换气体的通道。皮孔的形状,颜色和分布的疏密程度,也因植物而异。

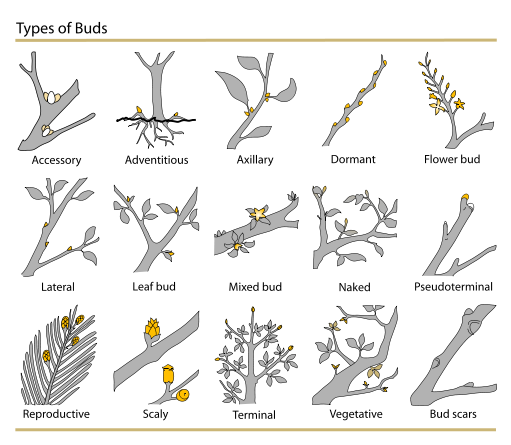

芽(bud)是枝、花或花序的雏体。以后长成枝的芽称为叶芽,长成花或花序的芽称为花芽。

accessory bud:副芽

adventitious bud:不定芽

axillary bud:腋芽

dormant bud:休眠芽

lateral bud:侧芽

pseudoterminal bud:假顶芽

repoductive bud:再生芽

scaly bud :鳞芽

terminal bud :顶芽

vegetative bud :叶芽

根据芽在枝条上的位置、芽鳞的有无、将发育成何种器官以及其生理活动状态,可以把芽划分为以下几种类型。

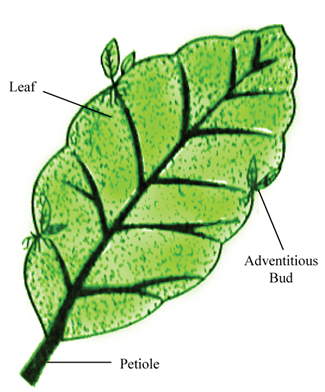

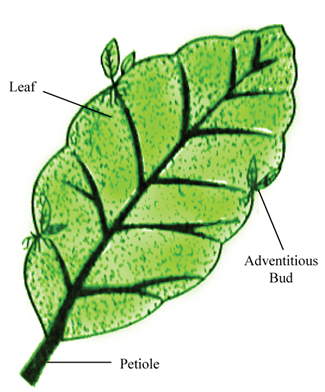

(一)依据在枝上的位置,芽可分为定芽(normal bud )和不定芽(adventitious bud )。定芽发生位置固定,又可分为顶芽和腋芽两种。顶芽是生在主干或侧枝顶端的芽,腋芽是生长在枝的侧面叶腋内的芽,也称侧芽(图3-1)。一个叶腋内通常只有 一个腋芽,但有些植物如金银花、桃等的腋芽却有多个,其中后生的芽称为副芽。有的腋芽藏在膨大的叶柄内部(被称为“柄下芽”),直到叶落后,才可看到,如悬铃木(图3-3)、刺槐等的腋芽。不定芽发生位置不固定。如甘薯、蒲公英、榆、刺槐等的芽生在根上,落地生根和秋海棠的芽长在叶上,桑、柳等的芽长在老茎或创伤切口上。植物的营养繁殖常利用不定芽。

(二)依据芽鳞的有无,芽可分为裸芽(naked bud)和鳞芽(scaly bud)( 或被芽)。木本植物的越冬芽外面都有鳞片包被。鳞片,也称芽鳞,是叶的变态,有厚的角质县,有时还覆盖着毛茸或分泌的树脂、黏液等,可降低燕腾、防止干旱和冻害,保护幼芽。有些植物的芽,没有芽鳞,由幼叶包着,称为裸芽,如黄瓜、棉、蓖麻、油菜、枫杨等的芽。

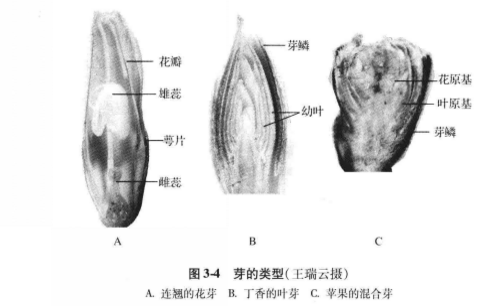

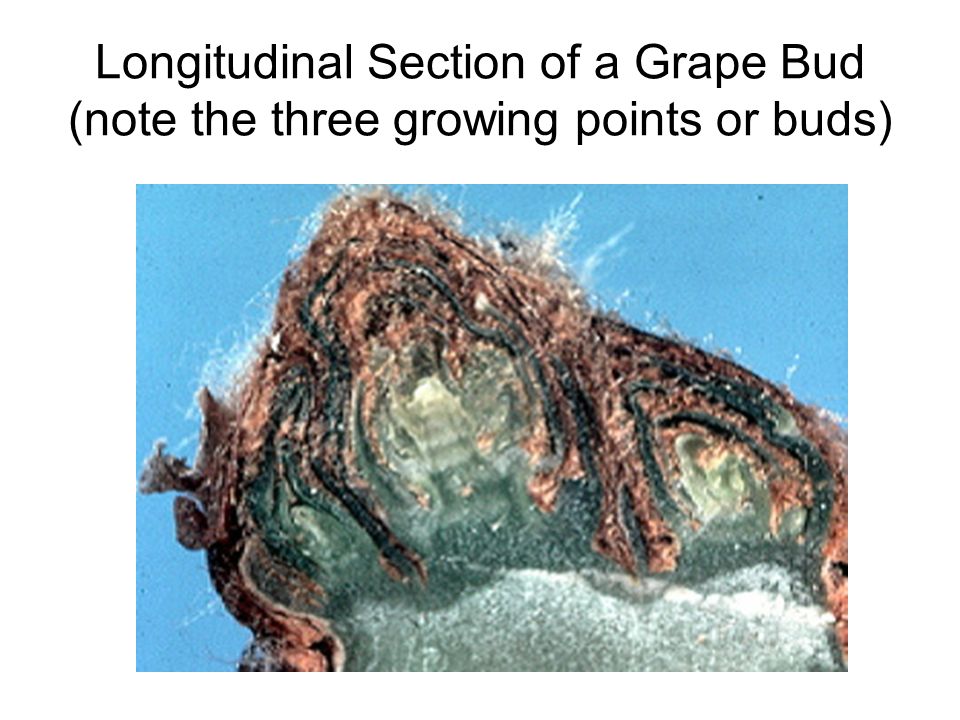

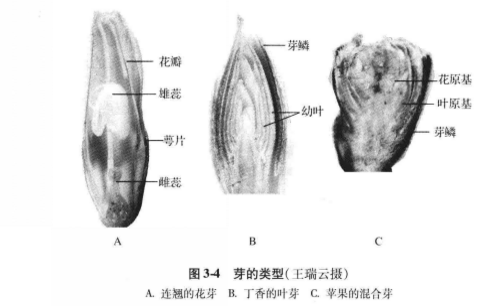

(三)依据将发育成的器官,芽可分为叶芽(leaf bud)、花芽(flower bud)和混合芽 (mixed bud)。叶芽萌动后发育为枝条(图3-4B)。花芽(图3-4A)是花或花序的雏体,由花原基或花序原基形成。

一个芽展开后既有枝叶、又有花的芽称为混合芽(图3-4C),如梨,苹果等的芽。玉兰、紫荆等是花先叶而开的,花芽先展开,开花后叶芽才开始活动,因此,花芽和叶芽易分辨。叶芽通常瘦小,花芽和混合芽大而饱满。

Definition of mixed bud :

a bud that produces a branch and leaves as well as flowers

(四)依据生理话动状态,芽可分为活动芽(active bud)和休眠芽(dormant bud)活动芽是在生长季节形成新枝、花或花序的芽。一年生草本植物的多数芽都是活动芽。多年生木本植物,只有顶芽和近上端的腋芽是活动芽,大部分的腋芽在生长季不萌发,称为休眠芽或潜伏芽。休眠芽中贮备的养料可供给活动芽。

Buds are often useful in the identification of plants, especially for woody plants in winter when leaves have fallen.[4] Buds may be classified and described according to different criteria: location, status, morphology, and function.

Botanists commonly use the following terms:

for location:

terminal, when located at the tip of a stem (apical is equivalent but rather reserved for the one at the top of the plant);

axillary, when located in the axil of a leaf (lateral is the equivalent but some adventitious buds may be lateral too);

adventitious, when occurring elsewhere, for example on trunk or on roots (some adventitious buds may be former axillary ones reduced and hidden under the bark, other adventitious buds are completely new formed ones).

for status:

accessory, for secondary buds formed besides a principal bud (axillary or terminal);

resting, for buds that form at the end of a growth season, which will lie dormant until onset of the next growth season;

dormant or latent, for buds whose growth has been delayed for a rather long time. The term is usable as a synonym of resting, but is better employed for buds waiting undeveloped for years, for example epicormic buds(外胚芽);

pseudoterminal, for an axillary bud taking over the function of a terminal bud (characteristic of species whose growth is sympodial: terminal bud dies and is replaced by the closer axillary bud, for examples beech, persimmon, Platanus have sympodial growth).

for morphology:

scaly or covered (perulate), when scales, also referred to as a perule (lat. perula, perulaei) (which are in fact transformed and reduced leaves) cover and protect the embryonic parts;

naked, when not covered by scales;

hairy, when also protected by hairs (it may apply either to scaly or to naked buds).

for function:

vegetative, if only containing vegetative pieces: embryonic shoot with leaves (a leaf bud is the same);

reproductive, if containing embryonic flower(s) (a flower bud is the same);

mixed, if containing both embryonic leaves and flowers.

一、茎的基本特征与生理功能

Buds are embryonic branches or flowers in a dormant state ready to resume growth when it gets warm again. The buds of most species are protected by tough bud scales. Bud scales can either be arranged in pairs facing each other edgewise (valvate bud scales) or overlapping like shingles (imbricate scales). A few species have naked buds that lack scales and are protected instead by a pair of miniature leaves.

Bud scale examples (left to right):

Bud scale examples (left to right):

1. Flower bud, cross-section, of horse-chestnut (Aesculus hippocastanum) showing bud scales.

2. Valvate bud scales of tulip-tree (Liriodendron tulipifera).

3. Imbricate bud scales of sugar maple (Acer saccharum).

4. Naked buds of witch-hazel (Hamammelis virginiana).

During the growing season lateral buds develop just above the point where the leaf rises off the stem. At the apex of a twig there may be a terminal bud that is larger than the laterals and points strictly forward. Some twigs lack a terminal bud, having instead a false terminal bud at the end of the twig which is actually the last-formed lateral bud. Alongside a false terminal bud look for the tip scar — a remant of the sloughed-off portion of the branch tip that formerly extended past the bud. Oaks are noted for their clustered end buds that are actually lateral buds with very short internodes crowded towards the end of the twig.

Bud examples (Left to Right): 1. Basswood (Tilia americana) lateral bud.

Bud examples (Left to Right): 1. Basswood (Tilia americana) lateral bud.

2. Basswood false terminal bud and tip scar.

3. Bitternut hickory (Carya cordiformis) with true terminal bud distinctly larger than laterals.

4. Clustered end buds of chinquapin oak (Quercus muhlenbergii).

Leaf scars and their bundle scars, Bud-scale scars, Fruit scars

When a leaf falls from a branch at the end of the growing season, a rough patch reamins under its base, the leaf scar, within which there are one or more bundle scars –remnants of the “plumbing” (vascular system) connection that extended between the veins of the leaf and the branch. Leaf scars come in many distinctive shapes and sizes, and the number and distribution of bundle scars is distinctive, too.

A useful feature to determine the age of a twig (or how much growth occurred in one season) is an array of several narrow, crowded, bud scale scars left where the scales fell from a true terminal bud at the initiation of the growing season. When fruits fall off a tree, sometimes they leave a fruit scar.

Various scar examples (Left to Right):

Various scar examples (Left to Right):

1. Large leaf scar of tree-of-heaven (Ailanthus altissima) with U-shaped arrangement of bundle scars.

2. Eliptical leaf scar of sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua) with three distinct bundle scars.

3. Bud scale scars marking the end of one year’s growth and on red ash (Fraxinus pennsylvanica).

4. Buckeye (Aesculus glabra) fruit scar.

…and stipule scars

Some leaves have stipules: little leaf-like apendages at base of the leafstalk, where it joins the stem. Because they’re attached to the twig, stipules, when they are shed, may leave a stipule scar. In a few species the stipule scars are very prominent, wrapping entirely around the stem. (Other plants have shorter stipule scars, occurring as short lines extensing down from the corners of the leaf scar.)

Tulip-tree (Liriodendron tulipifera) stipules and twig showing stipule scar completely encircling the twig.

Tulip-tree (Liriodendron tulipifera) stipules and twig showing stipule scar completely encircling the twig.

Ouch! (spines, thorns, and prickles)

Although they both hurt when you grab them (or if you are a deer, when you try to eat twigs that have them) there are slight anatomical differences between the various types of plant armature. Spines are modified leaves or stipules and as such are generally thinner and shorter than thorns, which are modified branches. Prickles are slender outgrowths of the epidermis.

Armature examples (Left to Right):

Armature examples (Left to Right):

1. Stipular spines of blacklocust (Robinia pseudoacacia).

2. Thorn of hawthorn (Crataegus crusgallii).

3. Raspberry (Rubus allegheniensis) prickle.

…and other surface features

Plant surfaces usually lack hairs (i.e., are glabrous), so when we see ones that are pubescent (hairy), they stand out. Similarly, twigs may be smooth or have wing-like ridges, depending upon the species. The surface of the twig is often a good feature to distinguish otherwise similar species within a genus.

Twig surface examples (Left to Right):

Twig surface examples (Left to Right):

1 and 2. Pubescent and glabrous twigs of staghorn sumac (Rhus typhina) and smooth sumac (R. glabra).

3 and 4. Winged and smooth twigs of blue ash (Fraxinus quadrangulata) and green ash (F. pensylvanica).

二、茎的皮

茎的皮